Sometimes reinforcement training gets confused with coercion—I myself had this confusion for quite some time, first implicitly then more explicitly from having read Perceptual Control Theory (PCT) books.

Then I read Don’t Shoot the Dog, a book on reinforcement training, and realized that I was approximately confusing threat and punishment and reward… with creating a good learning gradient for someone.

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.

– Aristotle

What causes us to repeatedly do things? They work. What causes us to do different things? They seem to work better. This is how learning works.

So if you want an organism—yourself, a spouse, a pet, a kid, a coworker—to learn to do something different, then you need to give them some sort of gradient along which they try new things and those things seem to work better. You need to meet them in the adjacent possible, and encourage them along it.

Video games are excellent at this—they start easy, then get progressively harder as you go. At each stage, you need to figure out what works to get you to the next stage. If you got thrown into level 48 at the start, you’d be totally overwhelmed.

This is the idea with shaping: using some reinforcer and a sequence of behaviors that work at each step.

Reinforcement is not reward. Arguably it’s a subtype of reward, but unlike the typical connotation of “reward”, here you need dozens or hundreds of little instances (or in the case of training LLMs, trillions), and more critically it needs to come immediately. Seconds is too late. So it’s a very different vibe.

When my wife and I read Don’t Shoot the Dog, we were in Australia with her family for Christmas, and her folks have a dog named Eddie. Using lentil-sized pieces of meat, we spent a couple days shaping him to lie down.

This was pretty easy, in part because we could use the presence of the meat in our hand—which got his attention and tended to get his nose to follow—to guide him from a seated position to a lying down position. Then the trick was to figure out how to get him to do that while we backed up and moved the “down” gesture so that it wasn’t happening right in front of his nose, but rather from us at standing height.

But all told we taught the old dog a new trick in a couple days, despite ourselves being totally new to the training method.

One of the skills they don’t tell you you’ll need when you become a parent is improvisationally automating and delegating things. Maybe some parents don’t do this, but I did a lot. I don’t like being a laptop employed as a nightlight. So in the first few months of parenting, when I found myself with the job of “simply hold the bottle while the baby drinks”. I figured out ways to better prop the bottle up: give it more balance points by attaching a small cheap carpenter’s clamp to it. Soon my intrepid daughter was holding it herself, merely reflexively—this is her at 3.5months, a good few weeks before she learned even to just see an object and reach for it.

Something they do tell you about parenting is that there will be regressions—the newborn who sleeps so easily becomes a 4mo who sleeps very erratically until you give them really clear consistent sleep associations and help them learn to bridge from one sleep cycle to the next. But it had not occurred to me that after my baby around 7mo learned to hold the bottle herself without the clamp… that she would some day soon become unable to feed herself with the bottle.

That day came at around 10 months, when she learned to sit up. See… she hadn’t learned about gravity. When she was laying on her back, merely holding the bottle in her mouth at all (usually at about the angle in the above photo) would result in the milk flowing. But once she could sit up, well, gravity wasn’t on her side. Suddenly she was frustrated, but she refused to drink laying down. Fair enough, but it meant I was once again employed below my pay grade.

It took me another 2 months before it occurred to me to try this, but one night it occurred to me to try shaping—at worst, I would entertain myself more than just sitting there holding the bottle up. The regime was simple:

She only has one bottle a day, at bedtime. One night, I went through that process and it took the whole 20 minutes or so of the feed to get any moments of the last step. I would back up if it seemed too hard. The next night, within 5 minutes she was feeding herself. The following night I just handed her the bottle and she grabbed it and tilted it up. And every night since, although sometimes someone enjoys holding and feeding her anyway.

I don’t know if it would have worked earlier, but my guess is yes given how fast it worked when I did it. Might’ve taken longer at 10mo—and I’m not 100% sure she was strong enough at that age but she was climbing a lot so probably. Endurance though.

So I taught my baby a skill.

I’m mostly writing for my past self here. I legit used to think that all such training regimes were coercive.

I want to suggest that the two issues with coercion are:

It’s maybe already obvious how the above situations don’t have these issues, but let’s spell it out:

I used to think that the act of giving the reinforcer conditionally was somehow coercive.

I now mostly would pay attention to whether the organism seems to be engaging in the process with interest or frustration, and as long as you’re in the interest zone, ie the zone of proximal development, the conditionality feels like a fun puzzle. And, moreover, if the learning conditions are somehow demeaning, rather than an attuned loving challenge, then even if the task is in the adjacent possible, then, well, something bad is happening. Is it coercion? It might be some other problem. Importantly, for shaping to work, the conditionality needs to be so small that within seconds of them trying different stuff, something they do is further along the path and so they get reinforced. So there’s no experience of it being withheld.

A more subtle confusion, likely held only by those who have engaged with Perceptual Control Theory and its beef against behaviorism, is that the situation required in order to do a training regime are themselves coercive or otherwise require total captive control of an organism’s environment, because that’s the only way that you can keep them ongoingly in a situation where you have control over something that they need (the reinforcer) so that you can use it to reinforce them. This one seems silly to me from the above examples. Like yes, I control the meat & milk, and the dog & baby can’t get more of them than I (or other caregivers) allow. But:

In fact, in both cases, the learning is going to go way better if the dog or baby is not hungry, because they’ll have more patience.

My impression is that BF Skinner used to keep his pigeons somewhat hungry—maybe this is necessary for some animals and not others. I haven’t not investigated. I’m not trying to say reinforcing/shaping is never coercion, just that it isn’t inherently coercion.

But also animal trainers often work with secondary stimulus—a simple click sound—for which the animal is clearly not operating in a state of deprivation. And the animal gets excited when it’s training time! I get to learn! What fun!

One reframe I found helpful for this is to think of the reinforcer as a signal of “that worked!”

It’s a more intuitive, 1st person, description of what a reinforcer is. It reinforces because it tells the organism what worked. It tells them what worked because it got them what they wanted, or it got them a sign that they would get what they wanted later, or because it got some signal that they were learning something worth learning. And sometimes the mere act of having some success with something you’re trying to do gives you that “that worked!” sign. But for forming superorganisms, we need to be able to tell each other what worked.

I have a video on this:

I also have another essay defining coercion in terms of PCT, which may be of interest.

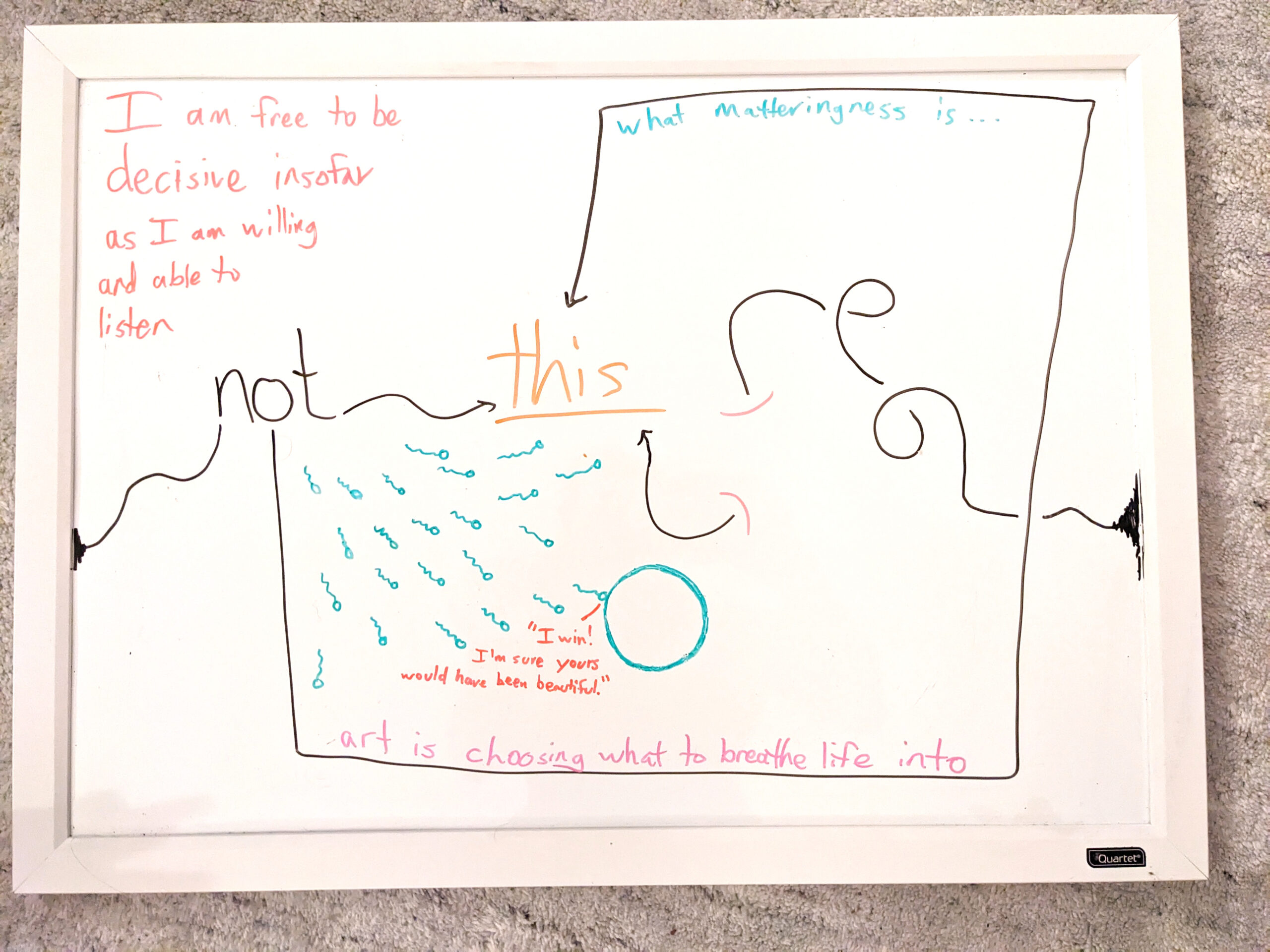

note to self: art is choosing what to breathe life into

art is choosing what to breathe life into

this?

not this

this? not this. not this. this?

this.

this!

sometimes I get stuck because I have more urges than I know how to handle

“I want to write”

“no I want to take a shower”

“but before I take a shower I want to work out”

“but I’m still partway through writing”

“wait but I’m kinda hungry”

“wait no but I don’t want to eat if I’m about to work out”

…and on. and on.

so many urges. so many things to take care of. I can’t do all of them, not all at once. I can maybe take care of all of them eventually… but by then there will be more.

I can probably take care of what needs taking care of eventually, on some level of abstraction, somewhere up in my perceptual control hierarchy

even thinking a thought is sort of an urge

hi urge

you’re tryna take care of something

these urges are helpful

while it may be challenging when they’re all tugging in different directions

…these urges are all really helpful

honestly, they’re kinda… made of helpfulness

» read the rest of this entry »The following is a piece I wrote a year ago. A few months back I started editing it for publication and it started evolving and inverting and changing so dramatically that I found myself just wanting to publish the original as a snapshot of where my thinking was at about a year ago when I first drafted this. I realized today that attempts to write canonical pieces are daunting because there’s a feeling of having to answer all questions for all time, and that instead I want to just focus on sharing multiple perspectives on things, which can be remixed and refined later and more in public. So, with some minor edits but no deep rethinking, here’s one take on what coercion is. And you might see more pieces here soon that I let go of trying to perfect first.

Coercion = “the exploitation of the scarcity of another, to force the other to behave in a way that you want”

The word “behave” is very important in the above definition. Shooting someone and taking their wallet isn’t coercion, as bad as it is. Neither is picking their pocket when they’re not paying attention. But threatening someone at gunpoint and telling them to hand over their wallet (or stand still while you take it) is coercion. This matches commonly accepted understandings of the word, as far as I know.

A major inspiration for this piece is Perceptual Control Theory, a cybernetic model of cognition and action, which talks about behavior as the control of perception. I’m also mostly going to talk about interpersonal coercion here—self-coercion is similar but subtler.

If someone has a scarcity of food, you can coerce them by feeding them conditional on them doing what you want. This is usually called slavery. One important thing to note is that it requires you physically prevent them from feeding themselves any other way! Which in practice usually also involves the threat of violence if they attempt to flee and find a better arrangement.

In general, a strategy built on the use of coercion means preferring that the coerced agent continue to be generally in a state of scarcity, because otherwise you would be unable to continue to control them! (Because they could just get their need met some other way and therefore wouldn’t have to do what you say!)

» read the rest of this entry »I am coming to the conclusion that everything I was trying to get myself to do is better approached by exploring how to allow myself to do it.

😤✋❌ how do I get myself to do the thing?

😎👉✅ how do I allow myself to do the thing?

It’s obvious, on reflection: if “I want to do the thing”, great! The motivation is there, for some part of me that has grabbed the mic and is calling itself “Malcolm”.

The issue is that some other part of me doesn’t want to do the thing, for whatever reason, or I’d simply be doing it. (To be clear, I’m not talking about skills, just about actions, that I’m physically or mentally capable of taking.)

So there’s a part of me, in other words, that isn’t allowing me to do the thing that I supposedly want to do (I say “supposedly” because the part claiming I want to is necessarily also partial).

…and that’s the part with the agency to enable the thing!

So the question is:

» read the rest of this entry »What’s the difference between positive & negative motivation?

I like to talk about these as towardsness & awayness motivation, since positive & negative mean near-opposite things in this exact context depending on whether you’re using emotional language (where “negative” means “bad”, ie “awayness”) or systems theory language (where “negative” means “balancing” ie “towardsness”). I have a footnote on why this is.

There’s a very core difference between these two types, both inherently to any feedback system and specifics to human psychology implementation.

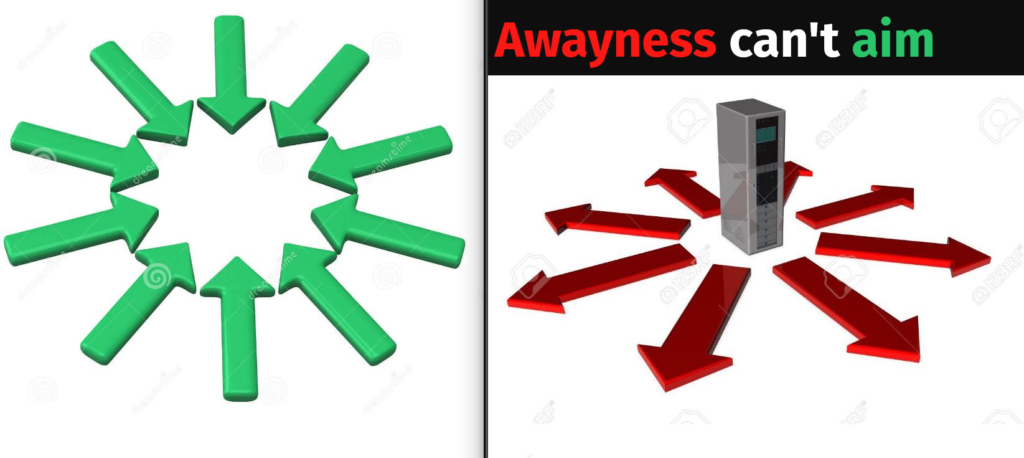

Part of the issue is (and this is why I say positive vs negative motivation are different in all systems) you fundamentally can’t aim awayness based motivation. In 1-dimensional systems, this is almost sorta kinda fine because there’s no aiming to do (as long as you don’t go past the repulsor). But in 2D (below) you can already see that “away” is basically everywhere:

Whereas with towardsness, you can hone in on what you actually want. As the number of dimensions gets large (and it’s huge for most interesting things like communication or creative problem-solving) the relative usefulness of awayness feedback gets tiny.

Imagine trying to steer someone to stop in one exact spot. You can place a ❤ beacon they’ll move towards, or an X beacon they’ll move away from. (Reverse for pirates I guess.)

In a hallway, you can kinda trap them in the middle of two Xs, or just put the ❤ in the exact spot.

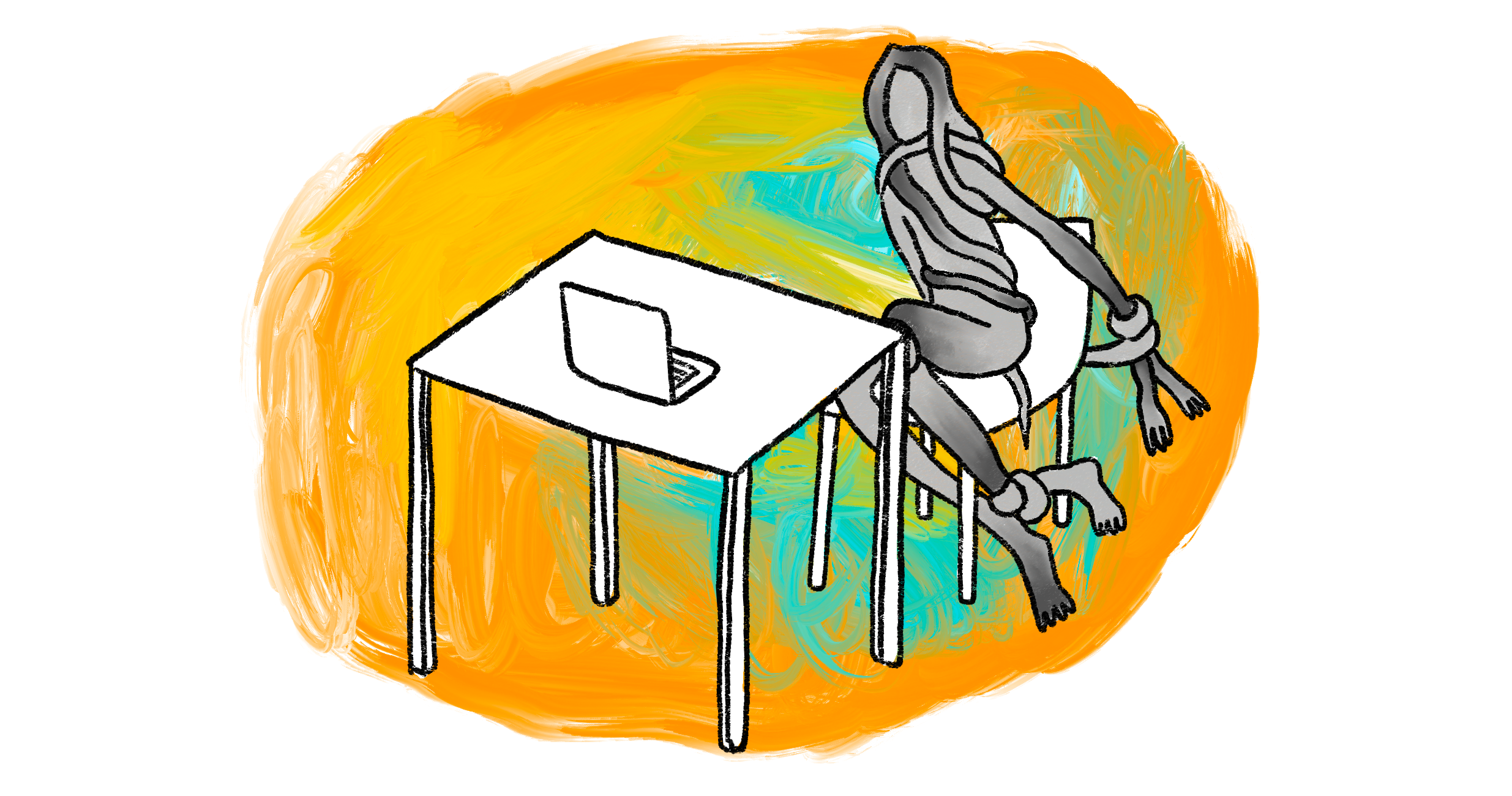

» read the rest of this entry »You know that thing where you spend a lot of time NOT doing something?

Like you can’t actively do anything else (spontaneously nor decisively) because you’re supposed to be doing the thing, but you’re also not doing the thing because of some conflict/resistance.

I’ve decided to call this knot-doing. (I have another post in the works called knot-listening). You can just pronounce the k if you want to distinguish it from “not doing” in the daoist sense. Or call the latter “non-doing” and be done with it.

Here are some examples of knot-doing:

You might be inclined to just call this “procrastination” but I think that knot-doing is a more specific phenomenon because it points at the lack of agency experienced while being in the state of not doing something—your agency is tied up in knots. A student may be procrastinating if they go to a party instead of working on their homework, but if they’re letting go and having fun at the party then it’s not knot-doing. I’m arguably procrastinating on fixing my phone’s mobile data after a recent OS upgrade, but I’m doing loads of other stuff in the meantime.

Unresolved internal conflict, most fundamentally. You’re a bunch of control systems in a trenchcoat, and if part of you has an issue with your plan, it can easily veto it and prevent it from happening. Revealed preferences can be a misleading frame, but if you leave aside what you think you want for a moment and look at yourself as a large complex system, it’s clear to see that if the whole system truly decided to do anything in its capability, it would simply be doing it. I want to type these words, my hands move to type them. Effortless.

Sex can be a workout, physically, depending on the position, but until we actually become tired, we usually also experience it as effortless when we’re so in the flow that we just want to do it. Same with dancing. Being in a flow state, whether work or play, is basically the opposite of knot-doing.

I want to break down my above statement: “You’re a bunch of control systems in a trenchcoat”. First, what’s a control system? The simplest and most familiar example is a thermostat: you set a temperature, and if the temperature gets too low, it turns on the furnace to resolve that error, until the temperature measured by the thermostat reaches the reference level that you set for it.

But what prompts you to adjust the temperature setting? You probably walked over to the thermostat and changed it because you were yourself too hot or too cold. You have your own intrinsic reference level for temperature, which is like a thermostat in you. Except instead of just two states (furnace on, furnace off), your inner thermostat controls a dense network of other control systems which can locomote you to adjust the wall thermostat, open a window, put on a sweater, make a cup of tea, or any number of other strategies (habitual or creative) to get yourself to the right temperature.

Without explaining much more about this model (known as Perceptual Control Theory) I want to point out an important implication for internal conflict, by way of a metaphor: if your house has separate thermostats for an air conditioner and a furnace, and you set the AC to 18°C and the furnace to 22°C……. you’re going to create a conflict.

What actually happens in this scenario?

» read the rest of this entry »“Having is evidence of wanting.”

— Carolyn Elliott (eg here)

This is true, and useful, on net, but can easily encourage an Over-reified Revealed Preferences frame, in that it doesn’t account for the emergent results of conflict! …which is what’s underneath most behavior, particularly confusing behavior. By ORP I mean, assuming that you or others want exactly what’s happening, for some specific reason, as opposed to it being the attractor basin they found themselves in given various pressures in multiple directions.

When my partner Sarah & I walk, I sometimes end up about a foot ahead. We were reading some shadow shit into this (power dynamics!? respect!?) until we realized that I just have a faster default pace, & my system would only slow down once the error of me being ahead reached about 1′; she had a similar threshold for speeding up.

Hence me being one foot ahead was a stable point, what Perceptual Control Theory (PCT) calls a “virtual reference level” formed by two control systems in a tug of war (the tug of war being about walking speed, not position). The speed we were walking was also at a virtual reference level that was a compromise between our two set-points.

Neither control system wants the current situation, but neither has unilateral access to a move that would improve things in terms of what they do want. The gap was erroneous to both of us, but in order to close it, I would have to slow down or she would have to speed up, and neither of us had decided we would do that and shifted our overall mood towards walking to be compatible with the other.

So yes, the fact that part of you wants some shit that is socially unacceptable and/or bizarre from the perspective of your conscious desires, doesn’t mean that want is any more true or real than what the other parts of you want, and the want may not even really be direct.

Your shadow stuff may be “deeper” in the sense of “more buried” but that doesn’t make it “more profound” or whatever. All the things you consciously want also matter!

» read the rest of this entry »This post consists primarily of a lightly-edited text of a chat-based coaching exchange between Malcolm (M) and a participant (P) in a recent Goal-Crafting Intensive session, published with permission.

It serves several purposes I’ve been wanting to write about, which I’ll list here and describe in more detail at the end:

(One piece of context is that “EA” stands for “effective altruism”, a philosophy that does a fair bit of good in the world but also causes many of its adherents to panic, burn out, or otherwise tie themselves in knots.)

Without further ado, here’s the conversation we had:

P: I’m thinking useful next steps might be planning out how to explore the above; the ML-work will come relatively naturally as part of my PhD, whereas the science communication could take some fleshing out.

I feel a little discouraged and sad at the prospect of planning it out.

M: Mm—curious if you have a sense of what’s feeling discouraging or sad about the planning process

P: My sense is that if I plan it out it’s somehow mandatory? Like it becomes an “assignment” rather than a goal, like I have to persevere through even on the days where I don’t want to.

M: Here’s a suggestion: write a plan out on a piece of paper, then burn it

(inspired by the quote: “Plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”)

P: That was fun! I guess I’m very much a “systems” man, I have this fear that nothing will get done if it’s not in the system. But that might be detrimental motivationally for stuff like this.

M: Hm, it sounds like you have a tension between wanting to track everything in the system but then feeling burdened by the system instead of feeling like it’s helping you

P: That definitely strikes a cord (as well as your points, George, about separating “opportunities” from tasks). I guess I’m worried that I won’t get as much done if I’m not obligated to do it, or that it’s somehow “weak” to not commit strongly. But for long term growth, contribution and personal health, that’s probably not the way to go.

M: Yeah! If you want, we could do some introspection and explore where those worries come from!

(we could guide you through that a bit)

I don’t often pick fights, but when I do, I pick them on Twitter, apparently.

The Law of Viral Inaccuracy says that the most popular version of a meme is likely to be optimized for shareability, not accuracy to reality nor the intent of the original person saying it. On Twitter, this takes the form of people parroting short phrases as if everybody knows what words mean. One of the phrases I felt a need to critique is Dilbert creator Scott Adams’ “systems, not goals”.

This blog post is adapted from a tweetstorm I wrote.

The term “pre-success failure” from Scott Adams’ book is a gem. His related idea that you should have systems and not have goals is absurd. (have both!) Scott cites Olympic athletes as examples. 🤨

Take 3 guesses what goal an Olympic athlete has… 🥇🥈🥉

Systems don’t work without goals.

You need a goal in mind in order to choose or design what system to follow, and it’s literally impossible to evaluate whether a system is effective without something to compare it with. Implicitly, that’s a goal. (Scott Adams uses a somewhat narrower definition, but of course people just seeing his tiny quote don’t know that!)

We know certain Olympic athletes had good systems because they got the medals. They designed those systems to optimize for their athletic performance.

Lots of other Olympic athletes also had training systems, but their systems didn’t work as well—as measured by their goals.

I’m part of a team that runs a goal-setting workshop each year called the Goal-Crafting Intensive (where part of the craft is setting up systems) and the definition of goal that we use in that context is:

This article was adapted from a late-night Captain’s Log entry of mine from last April. I did most of the edits at that time and thought I was about to publish it then, and… here we are. That delay is particularly amusing given the subject-matter of the post, and… that feels compatible somehow, not contradictory!

I’ve done a bit of writing since then, getting back in touch with my intrinsic motivation to blog without any external systems. We shall see when any of that ends up getting published going forward. I am publishing this now because:

One interesting evolution is that ppl prefer to see things unpolished rather than perfected

Perhaps because it’s more relatable

You squint + you can see yourself doing it

What caused this change?

This trend is only increasing, + may explain why we'll (maybe) record everything

— Erik Torenberg (@eriktorenberg) January 8, 2019

The writing begins:

@ 12:30am – okay, I need to account for something

I woke up knowing today was a blog beemergency. I went back to sleep for 1.5h.

I got up, knowing today was a blog beemergency. I did Complice stuff, almost-all of it non-urgent.

I reflected late afternoon (above) knowing today was a blog beemergency. I did other stuff.

…and I had the gall to consider, around 10pm, that I might weasel.

(If you’re not familiar with Beeminder, “blog beemergency” means that I owe Beeminder $ if I don’t publish a blog post that day. Weaseling in this case would refer to telling it I had when I hadn’t, then (in theory, and usually in practice for me) publishing something a day or two later to catch up)

I don’t want to get into self-judgment here, but just… no. Weaseling undermines everything. At that point you might as well just turn it off or something. Except, bizarrely… part of me also knows that this Beeminder blog system does continue to work relatively well, despite my having weaseled on it somewhat and my having derailed on it regularly.

…in many ways, the Beeminder part of it is actually totally broken, except inasmuch as its ragged skeleton provides a scaffold to hang my self-referential motivation on—ie the main role that it provides is a default day on which to publish a blog post (and by extension, a default day on which to write) and it acts as a more acute reminder of my desire to be actively blogging. But… it’s not in touch with any sense of deep purpose.

…I don’t have that much deep purpose that generates a need to blog regularly. And it’s nebulous the extent to which my sense of deep purpose is connected with needing to blog at all, at the moment.

I do have the sense of having relevant things to say, but I’m—hm. Part of it is like, the strategic landscape is so up-in-the-air. Like who is Upstart? What’s this Iteration Why thing, and where am I in relation to that? And how all of that relates to my other projects!

So then, I could be publishing other things that are more instrumentally convergent, independent of whatever exactly emerges there. When I look at my Semantic Development airtable though… a lot of this stuff actually feels like it would be pretty publishable, and I feel quite attracted to working on it… so what’s the issue? Why have I been doing so much Complice stuff, the last week, for instance?