You know that thing where you spend a lot of time NOT doing something?

Like you can’t actively do anything else (spontaneously nor decisively) because you’re supposed to be doing the thing, but you’re also not doing the thing because of some conflict/resistance.

I’ve decided to call this knot-doing. (I have another post in the works called knot-listening). You can just pronounce the k if you want to distinguish it from “not doing” in the daoist sense. Or call the latter “non-doing” and be done with it.

Here are some examples of knot-doing:

You might be inclined to just call this “procrastination” but I think that knot-doing is a more specific phenomenon because it points at the lack of agency experienced while being in the state of not doing something—your agency is tied up in knots. A student may be procrastinating if they go to a party instead of working on their homework, but if they’re letting go and having fun at the party then it’s not knot-doing. I’m arguably procrastinating on fixing my phone’s mobile data after a recent OS upgrade, but I’m doing loads of other stuff in the meantime.

Unresolved internal conflict, most fundamentally. You’re a bunch of control systems in a trenchcoat, and if part of you has an issue with your plan, it can easily veto it and prevent it from happening. Revealed preferences can be a misleading frame, but if you leave aside what you think you want for a moment and look at yourself as a large complex system, it’s clear to see that if the whole system truly decided to do anything in its capability, it would simply be doing it. I want to type these words, my hands move to type them. Effortless.

Sex can be a workout, physically, depending on the position, but until we actually become tired, we usually also experience it as effortless when we’re so in the flow that we just want to do it. Same with dancing. Being in a flow state, whether work or play, is basically the opposite of knot-doing.

I want to break down my above statement: “You’re a bunch of control systems in a trenchcoat”. First, what’s a control system? The simplest and most familiar example is a thermostat: you set a temperature, and if the temperature gets too low, it turns on the furnace to resolve that error, until the temperature measured by the thermostat reaches the reference level that you set for it.

But what prompts you to adjust the temperature setting? You probably walked over to the thermostat and changed it because you were yourself too hot or too cold. You have your own intrinsic reference level for temperature, which is like a thermostat in you. Except instead of just two states (furnace on, furnace off), your inner thermostat controls a dense network of other control systems which can locomote you to adjust the wall thermostat, open a window, put on a sweater, make a cup of tea, or any number of other strategies (habitual or creative) to get yourself to the right temperature.

Without explaining much more about this model (known as Perceptual Control Theory) I want to point out an important implication for internal conflict, by way of a metaphor: if your house has separate thermostats for an air conditioner and a furnace, and you set the AC to 18°C and the furnace to 22°C……. you’re going to create a conflict.

What actually happens in this scenario?

Assuming the two devices are about the same power, the temperature will average out to a compromise of about 20°C. How is this situation different from just setting both of the thermostats to 20°C in the first place?

“A good compromise is when both parties are dissatisfied.”

— Larry David

The furnace thermostat still wants* the temperature to be higher, and the AC wants it to be lower, so they’re actually both still running full-tilt, and wasting a ton of energy on a hefty power bill, whereas in the case where they’re both satisfied at 20°C, they shut off as long as the temperature is stable.

(*this use of “want” is only inappropriate anthropomorphization if you assume that it implies these devices are at all strategic, which they obviously aren’t. But it’s basically true to say that a control system “wants” to bring its measured quantity in line with its reference level. That’s in fact the only thing it wants, and is essentially what wanting is, in humans and animals as well.)

But that’s not all—in the non-conflicted scenario, if you leave the door open and let in a draft, the furnace will kick in to warm the house back up again. In this conflict scenario however, both thermostats are already in error, and already doing the best they can to correct the error in temperature, so instead the temperature just drops. It drops until it hits 18°C, at which point the AC shuts off because it’s cold enough, shortly after which the temperature suddenly jumps up because the furnace is still running. If there’s enough delay in the system, the house might reach 22°C by the time the AC turns back on, at which point the furnace is off and the AC is back on and you get a wild oscillation. This conflicted control system can ensure the temperature stays roughly between 18 and 22, but inside that range, it is completely out of control.

Familiar? Many people dread doing something for hours or days, then suddenly something kicks in and says “enough! we have work to do!” and they hustle hard on working, only to sooner or later have another voice say “enough! we’ve earned a break!” This can be a healthy balance, but for many people it’s an experience of whiplash and frustration—a compromise, not a win-win. The work feels stressed and the break feels rebellious rather than deeply restful or playful. Such conflicted control systems can keep you from becoming a complete couch potato or an utter workaholic, but can’t actually control anything beyond that because they’re caught in a tug of war.

Moreover, the stuck situation where things aren’t really going anywhere sounds to me an awful lot like that pre-oscillation situation, which is also completely out of control.

So we can now articulate slightly more precisely what’s going on with knot-doing. Knot-doing occurs when:

The unconscious careabout might be about the task itself, or about the way you’re attempting to do the task, or might be something much more general like a resistance to being told what to do.

“Being told what to do”—ahh, what a phrase. Therein lies a lot of confusion about motivation. I’ll get into this more in some future post but for now the key implication is that you’ll tend to get better results if you focus on the results you want to achieve and why you want to achieve them and let your body (or your employee, if you’re a manager) figure out exactly how it wants to solve it. This is much more conducive to flow states, because when you come up against some internal conflict, you can improvise around it rather than feeling like “I have to do X, and I have to not do X”. If you’re tracking the emerging conversation (eg on twitter) about shifting from coercive motivation to creative motivation, this is central to that.

I don’t have a simple answer for what to do about knot-doing, but I have some thoughts. In general, the best usual solution for you will depend on what sorts of things get you into a knot-doing conflict situation in the first place.

Described in more detail here, this approach basically consists of finding a way to utterly minimize the amount of time you’re spending on something.

When I was in university, in some of my courses we would sometimes get little assignments worth just like 2% of our overall grade. I found they could easily balloon out to take up hours of my time if I started them early, which felt not worth it, which would cause me to knot-do them. One term, I decided that instead of wasting my time that way, I would wait until 1h before the deadline to even find out what the assignment was, then hustle really hard to get whatever grades I could in one hour. If that was only 2/5 on the assignment, fine! I was happy to only spend an hour on it. Half the time I ended up getting full marks anyway but ymmv.

If you like this idea you might like showtimes. This blog post went live as a very half-assed draft based on a twitter thread, and then in the hours after it was published (before it got sent out on my newsletter) I overhauled the whole thing and added the PCT section above.

As far as I can tell, a very common cause of knot-doing is that part of me believes something to the effect of “if I wait long enough this problem will go away”, eg

In many of these situations, I’ve found that the main way the knot-doing resolves is that I actually let go of the situation. I leave the job or the project, or if it’s something personal I just decide I’m gonna drop it.

This is actually kind of like quitting in that the aim is to get out of the situation as soon as possible, but in this case the only way out is through.

At the point when you’ve set out to do something and you’re stuck, I will encourage you to realize that the notion you’d had that you would simply do the thing is probably a fabricated option that doesn’t exist and can’t be chosen.

Having said that, sometimes I’ve had success actually choosing to actually do it. If you haven’t tried that move, feel free to try it. But only try it once per thing—if choosing doesn’t work, more choosing is not the answer.

The main way I’ve found to do this is to decide more precisely: not just to do it, but to do nothing else until it’s done. This removes the conflict! Obviously this only works for projects, not your entire job, and you want to be specific about what “nothing else” and “done” each mean (are you going to eat? sleep?) For the moment of choice itself, I’ve found self-trust bets powerful, although they’re kind of weird.

It is pretty common to experience knot-doing in relation to one’s job—it is, in fact, one connotation of something being “work” (rather than “play” or “fun” or “rest”, perhaps). My friend Yatharth has a great quote on this: “Work is not the action you take. It is a state of mind. Work is whenever you’d rather be doing something else.”

Yatharth observes that sometimes simply stepping back and saying “I can do whatever I want. What do I want to do?” results in wanting to do the original activity that was feeling blocked, because you did actually have good reasons to want to do it, you just had to get back in touch with them. And, of course, sometimes it doesn’t.

There is no right thing to do. There is no right way to do it. There are situations and coworkers’ expectations and other stuff you care about, that may generate some sense of importance. That’s all still there even if you allow yourself to realize that in some sense you don’t know what you’re doing or you’d already be doing it, and create more space for flow.

Being stuck towards the supposedly-most-important thing is not more ethical than being in a flow state towards whatever your being wants to be in a flow state towards.

A lot of this is reminding me of Michael Ashcroft’s discussion of “expanding awareness”, in the context of Alexander Technique. If you’re in a flow state, great. If you’re not, you either know something you’d like to be in flow doing and you can step into that flow by narrowing your intention to that thing (your awareness may or may not also narrow)…. or your don’t know how to get from flow, in which case the thing to do is to expand your awareness so you can see a way to get unstuck and flowing again.

Transcending the “wasting time (k)not doing X” problem is why self-energizing motivation is a core principle of my company and all of the working relationships I cultivate. The idea is that everyone is free to do something else if they don’t feel like doing what is supposedly most important. This is not something we actually all know how to do yet, but we can create learning containers that help people develop more of this capacity internally and in their working relationships. This learning process requires enough slack and redundancy to avoid people trying to rely on each other in ways that lead to unmet expectations and chronic disappointment or frustration.

The deeper challenge involves organizing the environment so that what people feel like doing will somehow add up to everything that needs taking care of.. I talk about the puzzle in this short video, exploring how what feels important to do can come from external prompts or can sort of bubble up from within (if we give it space).

“If we give it space” points a bit at how it’s hard to be self-directed and operate from self-energizing motivation if you’re stuck in a situation (eg a boring job) where it feels like you need to force yourself to do shit in order to create enough space to listen to yourself.

A frame-shift is possible here though: if you really actually see that continuing to work your job is the best way to bootstrap to more freedom (which it may not be! but if it is…) then you may suddenly actually have intrinsic motivation to keep doing it for now, because now it fits strategically into a vision you feel excited about.

As I’ve now said in multiple ways: if you don’t have clear unconflicted motivation towards* something, that’s a sure sign that part of you thinks it would be bad (at least in its current form) and maybe even multiple parts! If the outside world isn’t stopping you, you must be stopping you. If you don’t know exactly why it makes sense to not do the thing, that’s a sign that you’re disidentifying with the part of you that’s stopping you. You’re implicitly saying “that’s not me. I want to do the thing.” It’s strikingly similar to someone who’s had a right hemisphere stroke saying “that’s not my hand” about their paralyzed left hand because they can’t move it and can’t fathom identifying with something they cannot control.

(To be clear, even if you don’t know how to do the thing, there’s still a night-and-day difference between feeling utterly stuck and in a state of knot-doing, versus actively creatively exploring potential options and waiting for insight if you’re out of ideas.)

If you encounter this, the thing to do is to find a way to create dialogue between these disagreeing parts, which may require first acknowledging that they don’t really trust each other—the obstacle is the way. There are many approaches to this; one I’ve been developing recently is called internal trust-dancing.

Marshall Rosenberg talks about this in his book on Nonviolent Communication. You can read more about it on Sarah’s HowToHuman public roam but the basic idea is that you acknowledge that you don’t have to do anything and that you’re actually choosing to do anything it is that you’re doing. Even if you’re being externally coerced in some way and are powerless to get in a situation of noncoercion, you’re still the one generating your response to that situation. I don’t have the experience to back that up, but Victor Frankl does:

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

— Victor Frankl, Man’s Search For Ultimate Meaning

Write “I choose to _______ because I want __________”.

One way or another, this can help you either get in touch with why the action is actually the best way to achieve what you want, or it can give you clarity that the reason you’re doing it isn’t worth the cost you’re bearing by doing it (possibly including the time and attention spent knot-doing it).

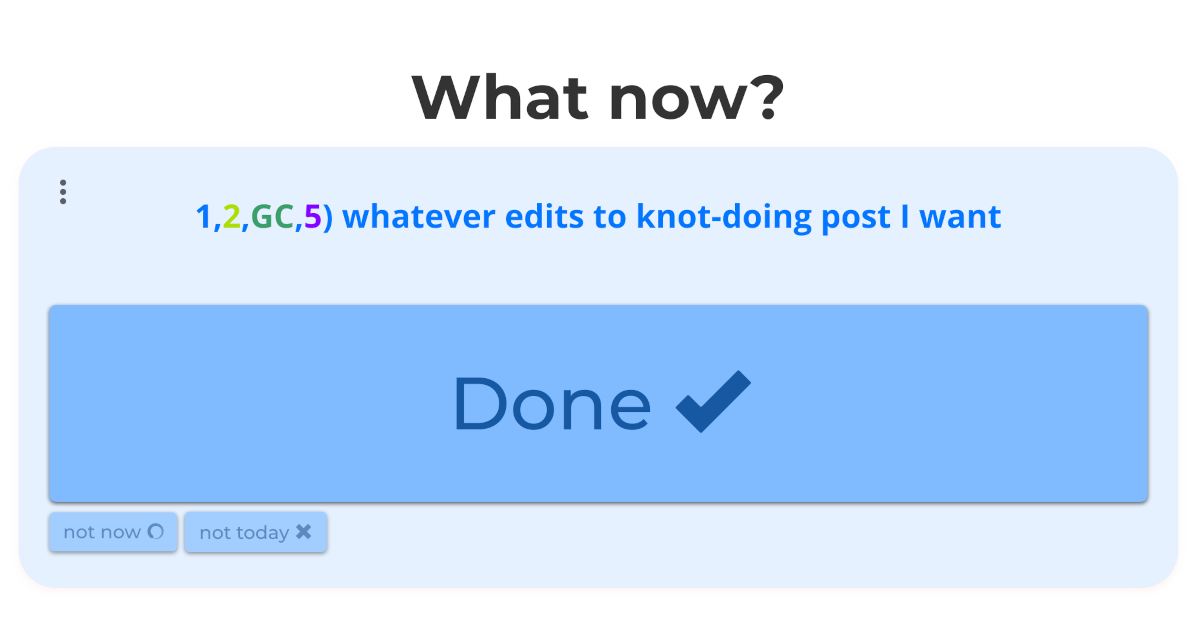

I have an interesting relationship with motivation, as someone closely involved in not just my own motivation process but the designer of a system used by hundreds of people daily to organize their attention towards what matters of them… and so Complice is always on my mind when I think about these puzzles, whether in the foreground or in the background. One way to think about its core workflow is “given what you care about long-term / big-picture, what do you feel like doing?” It usually asks that on a kind of one-day-at-a-time scale, but the latest update to Complice is a Now page, that just asks “what now?”

The workflow is very simple: you pick something to do, from a list or off the top of your head, then there’s just 3 buttons:

This interface encourages people to get really clear on what they’re doing in a given moment, and to set it aside if something else feels more alive. Or at least, that’s the idea. I suspect only some of the shift can be conveyed just in a new UI. Some of it people will have to learn theoretically, or at minimum they’ll need to unlearn whatever models of motivation they might already have that would get in the way of self-energized workflows. And blog posts like this help with that! But on the contrary, some people learn best by doing, and might internalize this blog post a lot better by trying out the Now page workflow for a week or two to see what it’s like.

(This Now Page workflow dovetails smoothly with the usual daily intentions & outcomes workflow and weekly review system of Complice. You can choose an item for Now from your intentions for today, and any items you set for Now go in your list of intentions and outcomes.)

I’m working, also, on some systems within Complice that will help people do metacognition when they get stuck so they can figure out how to be doing something better, whether that’s getting back on task, taking a break, or shifting to a totally different project that feels more alive.

Want to strategize with me directly on what to do about the things you’re knot-doing? We’ve got some more Goal-Crafting Intensive workshops coming up in January, that you can sign up for, and get a workbook with some exercises plus hours of coaching from me and a bunch of other coaches experienced in untangling internal conflict.

Related:

Constantly consciously expanding the boundaries of thoughtspace and actionspace. Creator of Intend, a system for improvisationally & creatively staying in touch with what's most important to you, and taking action towards it.

Have your say!