Epistemic status: I’m definitely onto something but don’t take my word for it.

There sometimes seems to be a tradeoff between confidence and humility. That apparent tradeoff comes from a subtle assumption, which is common yet false: that your experience and mine are supposed to be the same. Rudyard Kipling knew this:

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, yet make allowance for their doubting too.

If, indeed. If we could do that, that’d be great. But how?

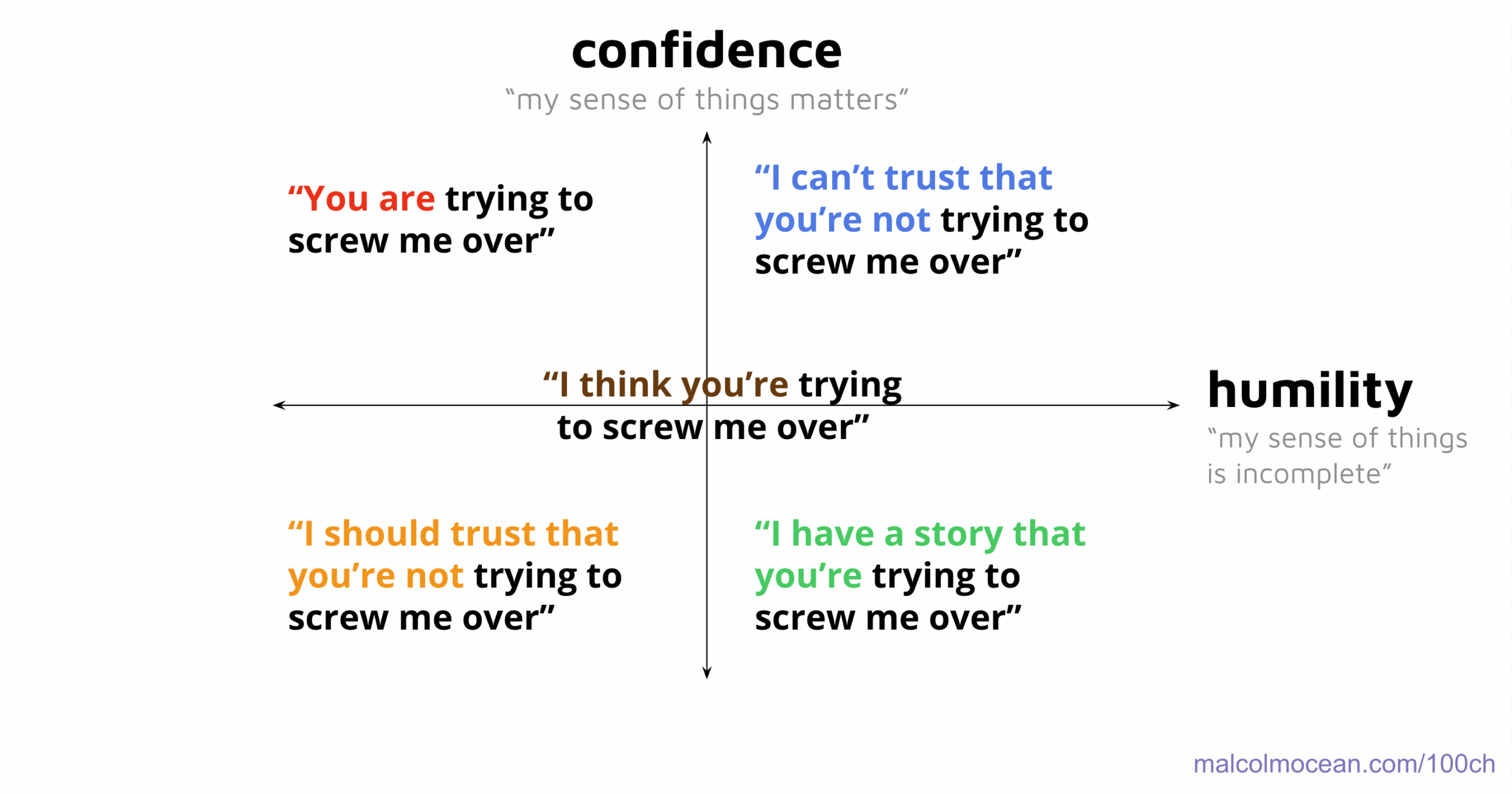

Consider these five expressions:

They’re all expressing a concern that the person is trying to screw you over. That part of the sentence doesn’t even change! What I’m going to say also applies to other second-halves of the sentence: “going to hurt me” or “lying” or “asking me to doubt myself” or “hiding something” or “overoptimistic” or “not on my side” or basically anything. I deliberately picked a contentious situation—one where it’s hard to talk without encountering issues. It’s contentious not just because of the tension in screwing-over, but because they refer not just to the other person’s behavior but their intent.

These phrases all express the same concern, but they express it in vastly different ways. They’re radically different speech acts—nearly as different as “what do you think about getting married?” is from “will you marry me?”. This isn’t just about the words, although words can help us understand how confidence and humility are not opposites but how you can have both or neither.

No transcending of a duality is complete without a 2×2:

Let’s talk about each of these different kinds of speech acts in turn.

This one is all confidence and no humility. In general this speech act is a claim, but in this context of talking about someone’s intent, this speech act is an accusation, which invites defending—or, if the accuser has sufficient social power, capitulating. Where the others are “I statements”, this one just tells it how it is. Except of course I don’t actually know how it is, I only know how it seems to me. This is especially true with statements like this one, which imply something about the other person’s intent.

» read the rest of this entry »My friends Harmony, Sahil, and James created a practice for relating called Stemless. They’ve written about it here. The core question of Stemless is “what does it take to own your experience?” Stemless is not prescriptive about how to do this, merely insistent that you keep attending to the question.

Unlike practices like Circling, in Stemless you don’t particularly try to own your experience by using stems like “I have a story that…” or translating your sense of betrayal into a body sensation plus a request or whatever. Instead, you’re invited to recognize the shocking fact that we are all in some ways exquisitely owning our experience simply by having it and by acting from it at all. Very dzogchen-flavoured (and, I think, -inspired).

There’s something about it that feels deeply relieving. Some sense of “wow, the right hemispheres just get to talk now, and the left hemispheres are a bit confused but along for the ride.” And a sense that it immediately gets to the meat of what’s actually going on, rather than caught up in endless preamble. Clarification is done not by backing up and pinning meaning down, but by beholding it in all of its nebulous glory and then saying whatever needs saying give however things seem to be landing.

And it’s not exactly a skill so much as a stance, although there are perhaps skills that can help scaffold the process of shifting stances.

In Dream Mashups, I write:

Everyone is basically living in a dream mashup of their current external situation and their old emotional meanings. Like dreaming you’re at school but it’s also on a boat somehow. And as in dreams, somehow the weirdness of this mashup goes unnoticed.

Stemless is about noticing the weirdness directly and bringing the emotional meaning into the foreground—at least for yourself, possibly also out loud. “I’m sitting in a classroom and the prof has tried to answer another student’s question, but he didn’t understand the question, and I’m supposed to re-ask the question but better, to get clarification.” That’s a thing I said at one point during tonight’s session.

It’s in part about noticing the supposing process, that creates the supposed-tos. Someone says something, or does something—or outside of a conversation, I notice something or read something—and I feel compelled to respond in a particular way. Quick: what is the scene I have just cast on the situation, such that that’s obviously the next move? You can’t tell me what mine is, although you have whatever you’re sensing and it might shine some light for me.

Leaning into blame

One playful thing that the Stemless hosts encourage is leaning into blame. One way to really see the situation you’re in is to find the way in which you feel a totally helpless victim—where reality is just forcing you to perceive things a particular way and there’s nothing you can do about it.

What will happen if you don’t say something immediately in response to what someone else said? It depends on the person or the situation, but various answers might be:

And then you can ask “why’s that a problem? who’s going to punish me? where is this urgency coming from? who’s forcing me to respond this way?”

Not to disagree with it or try to shift it, per se, just to take it as object and allow it to more fully exist as the force that is compelling you. Although indeed, once you bring it into conscious awareness, you’ll often find that the urgency vanishes and the compulsion fades. After all, if you’re doing something to please your mom and she isn’t even in the same timezone as you, well, maybe you will find that you don’t have to do it quite so urgently.

The point is not to enact the blame, but to see how the world you experience is pre-generated by a bunch of stories you don’t remember choosing. By externalizing the sense of where that all came from, you can see it more clearly than if you go looking for your interpretations as something you are already aware of doing. Your interpretations will just feel like reality. Your sense of things.

There’s a common trope in spiritual or personal development circles that what someone says about you says more about them than it does about you. Sometimes this will even be stated as the extreme “it has nothing to do with you; it’s all about them.” This is a confusion, in my view; if it weren’t for you doing what you’re doing, they’d be projecting some completely different weird thing onto you.1

But there’s also a deep truth to it worth seeing, and Stemless does a great job of pointing at that truth in direct experience, and actually taking it seriously.

“If that’s so…” it says… “…if everybody can’t help but speak only out of their own entire momentary visceral crazy world with even the smallest utterance… then what are we doing pretending there’s any such thing as small talk, or any such thing as real judgment?”

Someone just said a thing to you that feels kinda underhanded. Well, they may have not been honest on a surface level, but they’ve actually revealed to you in high-resolution their own construal of the situation by the precise way in which they avoided showing themselves. And then you feel some whole sort of way about that, because of all of the past experiences you’re projecting onto it in order to make sense of it. And that’s all going on in vivid detail for you—and maybe if you turn your gaze quickly enough you can glimpse it before you’re just acting into the story.

Right now: what is your situation? You’re at the end of reading a blog post, whether on my site or in your email inbox or some reader. What does that mean? What are you compelled to do right now? How does this last, more direct addressing of your situation change that from what it might have been if I’d ended with the previous paragraph? Can you glimpse it?

We’re all going around making sense of everything. We have different kinds of models that we use without even realizing it. A non-exhaustive loose sketch:

The first we mostly learn from direct experience.

The second we mostly learn from studying and reasoning, plus confirming that it doesn’t contradict our experience or our other related models.

The third type we largely get from seeing how other people think about things. These models have too many details for us to properly verify them for ourselves. They may also have reflexive effects where believing them causes you to acquire more evidence in their favour. We may be very influenced by the popularity of the ideas, or the status afforded to those who hold them.

But just because we can’t directly verify these models, doesn’t mean that our personal experiences don’t play a critical role in model adoption. It’s just that instead of it being directly obvious or based on conscious checking, instead it happens more out of our awareness, as more a kind of sudden click-match or a gradual subtle seduction.

Suppose that someone is living their life, and they keep being told what a man is and what a woman is, and finds themselves thinking “uhhh I keep being told that I’m a man/woman, but I resonate more with the description of woman/man”. There’s an experience they’re having, that they don’t know how to make sense of, and they feel like they can’t talk about this with anybody. Then they come across some writing or a podcast from someone about their experience of being transgender, and they go “OH!” and something clicks. The world makes more sense.

Meanwhile, suppose that someone is is living their life, and they keep being told that gender is completely a social construct and that they shouldn’t notice or care about differences between transwomen and ciswomen, but they find themselves thinking “but I really do feel differently in relation to them” whether it’s about safety or attraction or whatever else… There’s an experience they’re having, that they don’t know how to make sense of, and they feel like they can’t talk about this with anybody. Then they come across some writing or a podcast where people are talking about evolutionary biology and how these differences are real and matter, and they go “OH!” and something clicks. The world makes more sense.

How do people end up with crazy worldviews?

» read the rest of this entry »The verb “trust” basically can’t be conjugated in the imperative case, in my view. When people attempt to trust, the means by which they achieve this tends to be something more like “pretending” or “ignoring” or even “compartmentalizing”. And that’s a move you can make! But in my view if you do such pretending without realizing, then you’re confused, and I’d rather be honest about what’s going on.

When I hear people saying things like “trust this” / “he should trust me” / “I know I should trust…”

…I ask “but do I trust?” / “but does he trust?” / “but do you trust?”

I aim to get people in touch with the sense of what they can tell for themselves. Not trust as a thing that you try to declare or choose. And I orient towards the question of how that trust might be built.

Unpacking each of these examples:

If someone says “trust me/this”, I will comment to them something like “hm, well, conveniently I do trust that, although I wouldn’t pretend to if I didn’t” or I’ll say something like “well, I don’t currently trust that, but here’s what I would need in order to trust it…”. This is always only a guess—someone might be able to satisfy the letter of that constraint, but something would still feel off to me, at which point I’d go “huh, I still don’t trust it. interesting.”

If someone says “he should trust me”, then I’ll inquire eg “why do you think he doesn’t already trust you?” / “what do you think he’s concerned will happen?” / “what do you think you could do to earn his trust?” …and if someone protests that they’ve already done what they needed to do to earn his trust, but he still doesn’t trust them, then I’ll highlight that it’s not up to them what earns his trust, it’s up to him.

If someone says “I know I should trust…” then the whole reason this is coming up is because they don’t have what they need to trust whatever this is. So to some extent I’ll investigate where the should is coming from—have they been memed into thinking that trust is a virtue, in the abstract? And I’ll investigate whether that trust can be built, or if not, what to do about it.

“Trust” and “distrust” come through experience. It’s part of my basic sense of things. In other words, when someone says the world is a particular way, I can tell how much I trust their word by the extent to which my sense of the world changes as a result. When someone says they’ll handle something, I can tell how much I trust their followthrough by the extent to which it then seems to me like it’ll be handled without my needing to manage it. When someone says “that won’t be an issue”, my trust is the degree to which I am in fact no longer concerned as a result of them saying that.

the ground is kind of cold on my bare feet

but I trust I can handle it and this does not produce an objection

I don’t choose to trust—I listen and observe that I do trust

I listen and observe, and I may observe that I trust, or I may observe that I do not trust.

Why do we ever think otherwise? Why do we think we could choose it?

» read the rest of this entry »There’s a classic thought experiment called Newcomb’s Problem. It goes as follows:

Newcomb’s problem: You face two boxes: a transparent box, containing a thousand dollars, and an opaque box, which contains either a million dollars, or nothing. You can take (a) only the opaque box (one-boxing), or (b) both boxes (two-boxing). Yesterday, Omega — a superintelligent AI — put a million dollars in the opaque box if she predicted you’d one-box, and nothing if she predicted you’d two-box. Omega’s predictions are almost always right.

If you haven’t heard about this yet, you might as well take a moment to consider what you’d do.

While you do, here’s a quote by Robert Nozick in his 1969 analysis of it:

In his 1969 article, Nozick noted that “To almost everyone, it is perfectly clear and obvious what should be done. The difficulty is that these people seem to divide almost evenly on the problem, with large numbers thinking that the opposing half is just being silly.”

One argument is: what you do right now can’t control what’s already in the box, therefore obviously you should two-box and get more money.

The other argument is: if you think like that you will not get very much money at all, because there will be no money in the other box.

But doesn’t that second argument imply that the choice you make now can in some sense control the past? “Yes”, answers Joe Carlsmith in his Betteridge’s-Law-of-Headlines-violating essay Can you control the past?, “and this is a wild and disorienting fact”.

The whole essay is worth reading if you’re at all interested in the topic. My aim right now is to analyze this one beautiful hypothetical:

Imagine doing “tryout runs” of Newcomb’s problem, using monopoly money, as many times as you’d like, before facing the real case (h/t Drescher (2006) again). You try different patterns of one-boxing and two-boxing, over and over. Every time you one-box, the opaque box is full. Each time you two-box, it’s empty.

You find yourself thinking: “wow, this Omega character is no joke.” But you try getting fancier. You fake left, then go right — reaching for the one box, then lunging for the second box too at the last moment. You try increasingly complex chains of reasoning. Before choosing, you try deceiving yourself, bonking yourself on the head, taking heavy doses of hallucinogens. But to no avail. You can’t pull a fast one on ol’ Omega. Omega is right every time.

Indeed, pretty quickly, it starts to feel like you can basically just decide what the opaque box will contain. “Shazam!” you say, waving your arms over the boxes: “I hereby make it the case that Omega put a million dollars into the box.” And thus, as you one box, it is so. “Shazam!” you say again, waving your arms over a new set of boxes: “I hereby make it the case that Omega left the box empty.” And thus, as you two-box, it is so. With Omega’s help, you feel like you have become a magician. With Omega’s help, you feel like you can choose the past.

Now, finally, you face the true test, the real boxes, the legal tender. What will you choose? Here, I expect some feeling like: “I know this one; I’ve played this game before.” That is, I expect to have learned, in my gut, what one-boxing, or two-boxing, will lead to — to feel viscerally that there are really only two available outcomes here: I get a million dollars, by one boxing, or I get a thousand, by two-boxing. The choice seems clear.

Makes sense, right? Like if you had those experiences, with the monopoly money, that’s how it would feel.

And I would describe this as “you have gained trust in Omega’s prediction abilities”. You can tell for yourself that Omega can predict you effectively perfectly. Your sense of things includes this perfect predictor. Let’s contrast that with the scenario as presented:

Newcomb’s problem: You face two boxes: a transparent box, containing a thousand dollars, and an opaque box, which contains either a million dollars, or nothing. You can take (a) only the opaque box (one-boxing), or (b) both boxes (two-boxing). Yesterday, Omega — a superintelligent AI — put a million dollars in the opaque box if she predicted you’d one-box, and nothing if she predicted you’d two-box. Omega’s predictions are almost always right.

“Omega’s predictions are almost always right.” — says who?

» read the rest of this entry »A few years ago I had an idea for a game to help people practice the stance of orienting towards win-wins, and the skill of creatively finding win-wins. I came up with a tiny playable proof-of-concept that didn’t need any materials, and played it a few times. Recently I discovered that somebody had made it as a card game!

The basic premise is as follows:

I called the concept the “omniwin training game”. While collaborative games are not as common as competitive zero-sum games, there are still lots of them out there: Hanabi, Pandemic, The Mind, and of course many video games. However, most of them focus on coordinating your actions around a single shared known goal.

So for my tiny proof of concept, I used the medium of words. Each player would secretly pick some constraint a word could have—often based on the spelling but you could do “verb” or something else. I didn’t have specific rules for that. Then each person would take turns naming a word, and the players for whom that word worked would say “ding!” Initially I had the rule that players had to only offer words that satisfied their own constraint, but I found that when the game lasted more than a few minutes it was pretty obvious to want to say things like “‘banana’ doesn’t work for me, but it works for you, right?” and this felt within the spirit of things.

This version of the omniwin training game worked well enough, and produced one astonishing and instructive result I’ll tell you about at the end of the post, but it had the unfortunate property of feeling a bit too simple, and of the possibility of people making totally incompatible constraints and getting stuck forever until they give up. Of course, “we mutually recognize there is no win-win” is a kind of win-win on the meta-level… but it’s less satisfying. On the other extreme is…

…calculate every possible combination of every possible constraint and ensure they’re all satisfiable at once.

» read the rest of this entry »My friend Ivan is working on a project called the Applied Organic Alignment Lab and he asked me to write up my version of how I’d approach such a project, in this era. It’s written first as an invitation I imagined Ivan writing, followed by some of the preamble thoughts I had while iterating towards that invitation. I don’t hew to hard to it being a realistic thing for Ivan to say—I basically write the version of it that Ivan might write if he had access to every thought I’d ever had and all of my writing including unpublished stuff—which is interestingly meta/appropriate to this project itself!

I’m assembling a crew of 5-6 people for the purpose of creating a human+AI superorganism that will be the full-meta-trust kernel of a scalable high-meta-trust network.

The foundational hypotheses of this project are:

As Malcolm Ocean put it in his notes on [[homecoming]]:

I want you to have: everything that you actually deeply coherently want and the entire path of clarifying and realizing those wants, exactly how you want it, with other people who want it with you, accounting for all of the things that feel naive to you about the previous description.

I want everyone to have that, and, we have to start somewhere and with a smaller group, and what I want you to know is that if you are in and can access in yourself wanting the same for me, I’m game to invest in this relationship in order to make that happen for all of us.

What’s the aim?

A care attractor is a system that many distinct agents all have a vested interest in maintaining the health of, because its surviving and thriving enables their surviving and thriving. There are many kinds of examples of care attractors: families, cities, countries, companies, friend groups, communities, ethical systems, religions, myths, networks, platforms such as twitter.

Our aim is to create a conscious, reciprocally-amplifying care attractor: a system that has the property that the more we care for it, the more it cares for us. Where we get in way more than we put out. And where we trust that it has that property, and where it doesn’t just care for our main cares while shadowing our other cares, but ever-increasingly enfolds more and different aspects.

And of course it’s not going to be perfect at that on day one, but that’ll be what we’re ongoingly aiming towards as we steer its development.

» read the rest of this entry »Samesidedness refers to that lovely experience when you’re navigating some sort of interpersonal problem and instead of fighting/arguing etc, the experience is one of being on the same team trying to figure out what to do about the problem. There are various things that can get in the way of samesidedness, one of which is being too close, ie tolerating being involved with someone to a degree that is unworkable. But a different one is that you have a mistaken assumption that it won’t be possible to come to an outcome where both/all parties can be deeply satisfied at the same time. This exercise is intended to help with that. You can do it solo, prior to having a difficult conversation, or you could have a group do it together if there’s buy-in for that.

Consider what you want in relation to this situation: your careabouts.

You might just mentally enumerate them, or if you have a journal handy you might write them down.

Note that your concept of your careabouts is not the actual careabouts. You in some sense don’t actually know the full shape of your careabouts in advance, but on some level you know what you’re aiming for. The words are not the thing—someone might do something that theoretically matches some description you made of what you wanted, and that doesn’t mean “now you should feel satisfied.” It’s possible to be profoundly satisfied and profoundly surprised-by-how-that-happened at the same time. With sufficient skill at non-naive trust-dancing, it can even be common.

Get in touch with how it would feel for you to have all of your relevant careabouts be completely satisfied, and ground in the sense of how much you truly want that for yourself. Spend only the minimum attention needed imagining the details of how the careabouts get satisfied that you need to feel that satisfaction.

If some part of you objects, then try to include the objection itself inside what wants to be satisfied! For example, if the objection is “that would be naive,” then you could say “okay, maybe there are some versions of that would be naive. How would it feel to have these careabouts satisfied in a way that was not naive?” Or if the objection is “if I were completely satisfied, that would necessarily mean someone else were suffering as a result,” then you might include that with “clearly also one of my careabouts here is that other people not suffer in order for me to be satisfied. So suppose that somehow I achieve that—all my careabouts are satisfied, and other people aren’t burdened by that at all.” (Anyway, handling such objections is a huge topic on its own, but for now I’ll just say “do your best” and “it’s a learning process; it’s okay if you’re having difficulty!”)

Tap into what the other peoples’ careabouts might be. Not in that much detail, but a general sense.

What would have come up for them in step 1?

Imagine how the other people involved might feel if they also had their careabouts completely satisfied. Even more so here, don’t pay too much attention to how, yet.

While doing so, maintain the sense that you could also be completely satisfied.

You might find more objections here, particularly ones about an apparent impossibility of satisfying their careabouts while also satisfying your own. To those, you can say, “Yes, it may be impossible, given the available resources or even in some absolute sense, but suppose it were possible for me to be deeply satisfied and for the other person to be deeply satisfied. How would that feel?”

Orient to the actual situation and start trying to understand together what the collective set of careabouts are and how you might go about satisfying all of them.

Unless you’re in a leadership position or otherwise empowered to just call the shots in this situation, then ultimately you’d need to do this phase together, but you can also simulate it if you’re journalling before a conversation. If you’re doing that, I’d encourage you to question your assumptions about what the other person wants. “What is this really about for them?” Consider that you might really not know. This humility may also help you realize that even if you can act autonomously here, you might want to learn more first.

The important thing is that each person pays attention to their sense of what would actually deeply satisfy their own careabouts, and being willing to be surprised and update their concept of what they want or what the other person or people want. For instance, you might think you want to do a particular thing, only to realize that much more salient is a need to be heard and understood by someone about that thing not having happened at some time in the past, and that once you feel heard, you discover that in fact your original careabout doesn’t need any further addressing.

Tips for use: This practice is intended for use in relation to interpersonal conflict, though it can also be useful for internal conflict, as well as in general. It’s probably best to practice it with a concrete conflict first—something that can be well-described with a physical quantity—before trying it on a conflict about meaning, relationship, identity, or situations involving feelings like “I don’t feel heard” or “I feel betrayed.” The practice is also probably easier if it’s about a relatively fresh or new situation, although with sufficient skill and capacity it should be helpful for things tangled with resentment or regret as well.

This exercise maps onto the 3SED (3 Steps for Empowered Dialogue) technique, which is essentially the same process but for “what you know and understand” rather than “what you care about“. It’s for frame battles rather than object-level fights.

(another ~20 minute onepager. read the other posts written in this style here. for a longer take on the 3SED process and how to DO each of the steps, read the secret to co-gnosis)

(this post was written in about 20 minutes, in the “onepager” genre: my friend Visa’s challenge to explain your thing rapid-fire. my others: Non-Naive Trust Dance, Evolution of Consciousness, Bootstrapping Meta-Trust)