I’m excited.

I’m excited, because it’s working.

I’ve been trying for years to develop my sense of mindfulness and mental control, and I’m starting now to get a very direct taste of what that feels like.

And it’s thrilling.

So here’s what happened: last night, I was having a conversation with Jean (my friend, housemate, mentor and project partner) and the subject of epistemological arguments came up. I’ve had some conflict with some of my other housemates in this area, and while part of it is theoretical there is also a practical concern, because ultimately we base our decisions on what we (think we) know, and so has felt threatening to the relationships to be unable to use certain ways of communicating information. Threatening, I think, for both sides.

I want to note that this conflict isn’t a shallow one. I wrote last year about how I overcame some of my stress around the subject of astrology. It had been a hot topic for me for several years due to heated arguments with girlfriends-at-the-time-of-the-arguments. At my first CFAR workshop, I brought up some of this stress, in a controlled environment and then worked to calm myself down, and it gave me a strong sense of what this concept of againstness feels like. (The relevant post contains a video, if you want to see it in action.)

Have you ever been talking with someone, and the two of you essentially agree about the topic at hand, but you still find yourself arguing your point violently? You know what that feels like? That feeling is againstness. And it takes mental skill to extricate yourself from the mode of vehemently asserting the thing you believe so strongly, and to instead have a productive conversation about it. And that’s the skill I’m learning. » read the rest of this entry »

To wash or not to wash? That’s not the question. The question is how to even decide.

(If this is your first or second time on my blog, this background info might be helpful for context.)

Last summer, after living at Zendo56 for maybe a month, I was in the kitchen, getting ready to head to class. I had just finished using a glass jar, and I gave it a brief rinse in the sink then found myself wondering what to do with it at that point. (It’s worth noting that our dishing system includes, by design, an ample waiting area for dirty dishes.)

So the decision I found myself with was: do I put it back in the drawer, as I probably would if I were living on my own, or do I leave it to be thoroughly washed later?

Conveniently Jean was in the kitchen, drinking tea at the table. I turned to her and (with some deliberation so as to avoid merely asking her what I “should” do) asked her for help in deciding.

She posed two questions for me:

- If you leave the jar out to be washed, what will be the experience of the next person to interact with it?

and

- If you put the jar back in the drawer, what will be the experience of the next person to interact with it?

Whoa. That style of thinking was very new to me, and very appealing.

Fast-forward half a year and I use reasoning like in the jar story on a fairly regular basis. I’ve done a lot more thinking about what it means to take others’ perspectives; reading, talking, and thinking about words like “empathy”.

Perspective-taking is related to empathy but is more conscious. You might say that it involves active and intentional use of the same brain circuits that run the empathy networks, to really model other peoples’ experiences. Where the Golden Rule says “do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” perspective-taking as a mindset suggests “understand your own impacts by modelling how others experience your behaviours, from their perspective“. It’s not just walking a mile in another shoes, but walking with their gait and posture.

I’ve come to realize that while I do a decent amount of perspective-taking for basic decision-making contexts, I don’t actually do it much in other situations. This can sometimes lead to confusion around others’ behavior, and can lead to them feeling hurt or otherwise negatively affected by me. At the same time, this very pattern is part of what allows me to avoid having self-consciousness that might restrict my behaviour in ways I don’t want. A large part of what has allowed me to become so delightfully quirky is that I’m not constantly worried about what other people think. And ultimately other people do enjoy this. They’ve told me so, quite emphatically. So I don’t necessarily want to become immensely concerned about others’ perspectives either.

I attended a student leadership conference at uWaterloo yesterday, and one of the sessions was on personal branding and how to create the traits that you want other people to experience of you, in order to achieve your goals. I noted there that perspective-taking would be a valuable skill for any teamwork-related goals, of which I have many. Last night, I found myself asking, out loud, to Jean: what might happen if I were to adopt perspective taking as an intense, deliberate practice for a week. Could I build new affordances for modelling other people and their experiences?

(I’m using the secondary meaning of “affordance”, which refers to an agent having properties such that certain actions feel available to perform.)

Jean said “yes, and not just what’s going on for people, but what’s going on for…” and turned slightly to look roughly towards the kitchen table. “…the system!” I thought, and began considering the perspective of the cutting board, the knife. “The system,” she said. I began to talk about the knife and she said, “Not so much just the knife itself but the experience of everyone using the knife.”

Which, of course, brings us back to the jar story.

I decided to do it. To make that a primary focus of mine for this week, both here at the house and with friends and classmates. This is actually part of a larger behaviour-design experiment I’ve created for 2014. My reasoning is that rather than trying to change 50 habits all at once as a New Year’s Resolution, I’ll change 50 habits… in series, one per week.

My first of these was the lowering of the lavatory lid, so chosen because I share a bathroom with a housemate who experiences a raised lid with rather intense anxiety. Also to test-drive this. My second of these was to fix the out-toeing in my gait. Up until about 2 weeks ago, my feet usually had a ~90° angle between them while walking and often while standing.

Each of these has been a fairly solid success. They’re not fully unconscious habits yet, but it no longer takes additional energy to pay attention to them enough to maintain the change (while it becomes an ingrained habit). My third habit (which was to briefly mutter my intention every time I open a new browser tab) didn’t go so well, in large part because I was doing some work early in the week where I totally got into flow and (a) didn’t think of this and (b) would have experienced a net-negative effect from doing it. So I didn’t practice.

Week #4 is going to be perspective-taking. Unlike the first two, I’m not intending for this to produce a “complete” change in my behaviour, but rather to nudge my behaviour some noticeable distance from where it is now. To give me more affordances for taking others’ perspectives, until it starts happening regularly and naturally as part of basic relating with people.

I’ve set up a new page on these habits here.

PS: In case you were curious: I put the jar away.

In 2012, when I did my yearly review, I called it A Year of Projects, and suspected this one would be a Year of Text. Well, it wasn’t, and… I couldn’t be more delighted. This blog post is long, so feel free to skim it or jump around.

I set out to do this review in the form that Chris Guillebeau does, with a “what went well” and “what didn’t go well” (with an added “what went weird”†) but then I realized that this was prompting me to write about tiny wins and significant life-changers at kind of the same level. Instead, I’m going to structure this post around object-level things, process-level things, and meta-level things, which are kind of like “what”, “how”, and “why”. Click on the levels to jump down.

Object-level things are just things I accomplished. According to Remember the Milk, I ticked 938 things off this year, and that’s not counting other todo lists, but I’m only going to talk about big object-level things.

The first big one is launching my 3.0 update for FileKicker, which contains ads and has made me a bunch of passive income over the course of the year. This has had a huge impact, such as allowing me to afford the event in the next paragraph, and it’s crazy to think that I could have easily put it off for another day, another week, another month… another year. As it was, that launch was delayed by months, and I think precommitment could have been really helpful: “I commit to releasing my update by Oct 1st or I’ll pay you $200.” My lost ad revenue in those few months was worth more than that.

I went to an Applied Rationality workshop in January. One of my best decisions to date. I went on to mentor at 3 more workshops and have gotten immense value out of not just the material itself but also the alumni network. At that workshop, I released some pent-up angst I’d been holding against astrology, and learned about physiological stress response in the process. Watch me get really worked up then calm again over at this post.

Last weekend, I had a goodbye conversation. It followed this 6-step form, created by Steve Bearman of Interchange Counseling Institute. It was a really powerful framing for this communication that needed to happen.

Steps 2 and 3 of that process are apologizing and forgiving, which was interesting for me. As part of learning to embody the new culture we’re building with the Living Room Context (LRC; learn more here and here) I’ve been trying to live by a series of commitments and assumptions. One of these is:

I commit to offering no praise, no blame, and no apologies; and to reveal, acknowledge, and appreciate instead.

My friend Sean (who was actually spending the entire rest of the weekend at an Interchange workshop) was filling a counselor role and helping to hold the context for us. He and I have talked at length about the LRC and how I’m exploring communicating without apologies, so when we got to those steps, we agreed that it would make sense to take a moment to unpack those terms and figure out (a) what value was in each step and (b) what aspect of them felt incongruous with my mindset.

An apology, we teased out, has three parts:

Part 1 is the heavy part, where you say “I hurt you, and I own that.” Impact is important, despite it being undervalued in many contexts: consider “It’s the thought that counts”. Even though you didn’t intend to step on someone’s toe (literally or figuratively) it still hurts, and it’ll only hurt more if you try to minimize that. Intent isn’t magic.

Part 2 is saying you care. It’s where you communicate that it matters to you that you had a negative impact, and that you therefore want to fix that aspect of your patterns or whatever caused it. This part is what makes repeat apologies for the same thing feel awkward and insincere.

Part 3… well, that’s what the next section is about.

I want to tell a brief story. It takes place at the Household as Ecology, the LRC-focused intentional community house I lived in this summer. Jean is the owner of the house and one of the key people behind starting the LRC originally. This experience was a huge learning moment for me.

I was in the kitchen, and Jean had pointed out some way in which I’d left the system of the kitchen in relative chaos. I think I left a dirty utensil on the counter or something. I became defensive and started justifying my behaviour. She listened patiently, but I found myself feeling unsatisfied with her response. Finally, I cried out, in mock-agony, “FORGIVE ME!”

“No!” she responded with equal energy.

We both burst out laughing.

I want to pause and recognize that that story might be really confusing if you don’t have an appreciation for the context we’re operating in. Taken, quite literally, out of context, I can appreciate that that exchange might sound unpleasant, and confusing that it would end in laughter. (I’m curious, actually, if this is the case, and would love to hear from you in the comments how you understood it.)

I’m going to try to help make sense of it. What happened here was that even though Jean wasn’t judging me, I felt judged, and was trying to earn her approval again. I wanted to be absolved. Exculpated. Forgiven. But she couldn’t do that. To absolve someone is “to make them free from guilt, responsibility, etc.”… but to the extent that there was guilt, it was entirely inside me. And the responsibility? That’s there whether Jean notices what I’ve done or not. I remain responsible for what I’d done, and response-able to fix the current problem and change my future behaviour.

There was also a sense in which the dynamic of “if I forgive you, you’ll just do it again” applies. When this statement is said with resent, it’s painful, but Jean communicated this (implicitly, as I recall) with care and compassion and a sense of wanting the system to become better for everyone, and of wanting me to grow. Done in this way, it felt like a firmly communicated boundary, and the refusal to “forgive” felt like a commitment to continue giving me the feedback that I need. That I crave, even when it hurts.

From my experience, it’s possible to create a collaborative culture where forgiveness is superfluous. Where you have the impact that you have, and the other person may reasonably trust you less as a result, but they aren’t judging you or harboring any resentments in the first place, so this becomes meaningless.

During the conversation last weekend, what I tried doing instead of forgiveness (although I did try on that language, just for fun) was to communicate that I wasn’t holding any resentment or grudge: that I was not going to carry anger or judgement into the future. This is my default way of operating, and it felt really good to bring up the specific instances that hurt and to offer my understanding and compassion there.

The article linked at the top, that was providing the framework for our discussion, remarks the following:

Forgiveness comes from having compassion toward them and being able to imagine how, when everything is taken into account, their behavior was somehow constrained to be what it was.

When you take a systems-oriented perspective on things (rather than being caught up in a sense of entitlement for things being a certain way) this becomes the default model for everything. And so everything is already forgiven, to the extent that that’s possible.

All in all, this form facilitated us connecting and reaching a place of mutual understanding in a way that otherwise probably would simply not have happened. We had, in fact, tried to fix things before. What allowed us to get through this time was:

There was something about it being the end, that made it so we weren’t even trying to fix things. This helped give us the space to be honest and open, which in turn brought way more reconciliation than we thought was possible at that point.

I’m really grateful that I had the opportunity to do this, and that the others—both the facilitator and the person I was saying goodbye to—are adept, open communicators. This is what enabled us to go so deep and ask questions like “what are we intending to get out of this apologizing step?” and “what does it mean to forgive someone?”

Of course, my interpretation isn’t the only one. If you understand apologies or forgiveness in some other way, I’d be grateful to hear from you in the comments.

My aforementioned business now has a name: Complice. I’m sure I’ll write more about the name-choosing process later. This post is about various things I’ve learned in 73 days of business.

75 days. 11 weeks. It doesn’t feel like it’s been that long. I definitely had the sense of being at an earlier stage. But I guess I spent awhile going fairly slowly while I only had 1 user… which I didn’t even get stable until mid-October. So that’s half of the time right there, before I’d… done much of anything.

Wait.

I was already using a proto-Complice system at the time, so I can look up exactly what I did in there… Oh. I actually was spending a fair bit of necessary time on customer acquisition… plus walking my alpha user through things. I was also tweaking the planning questions a lot, which is funny given that I’ve basically ditched them for now. Oops. Well, learning. It’s not obvious how I would have realized their lesser importance at that point, esp since my single alpha user was doing them. Slowly though. Oh and blogging. I counted a lot of blogging. And here I go again! It’s important though, I think.

Once I’m actually loading this stuff into databases, I’ll be able to generate graphs and word clouds and other metrics about how much progress people are making over time.

Paul Graham writes “Startups rarely die in mid keystroke. So keep typing!” User-visible improvements are a commitment not to stop typing: that every day, some improvement to your product will be made available to your users.

It comes from Beeminder, who’ve just recently blogged about their thousandth UVI. My graph is much less grand, but it’s coming along. I’m tweeting my UVIs out at @compluvi. (My main Complice twitter account is @complicegoals)

The very system of Complice itself (which I’ve been dogfooding since before it existed) has been already keeping me making progress, but publicly committing to UVIs has the further benefits of communicating to users and potential users that I’m actively improving this, and ensuring that my progress is felt by my users, so I don’t spend most of my time on things like “answer their questions” and “read business book X”. Those are important, but I need to be actively improving things as well.

Having public commitment is really important. Early on, I would sometimes tell my idea to friends and they’d say “but how are you going to compete with X, Y, and Z?” and I would feel really discouraged, but I already had a half-dozen users who’d paid me to help them. I couldn’t just give up that easily. UVIs are kind of like saying “well, maybe I don’t have to make it to 20 pushups, but I can at least do 1 more… okay, and maybe 1 more”.

Blogging about Complice counts as a UVI because it’s definitely user-visible, and because a business with blog posts is better than one without. Of course, I have to do more than write blog posts, but bugfixes count too and they’re not sufficient to have a successful business either.

In the process of starting to work with my beta users, I continually experienced having my assumptions thrown out the window. I had assumed that: (time to realize; how I realized)

The first few assumptions were kind of silly, but other . I’ve been reading The Lean Startup by Eric Ries, and it talks a lot about having explicit experiments with stated hypotheses. This helps iteration/innovation proceed much faster and more nimbly because it doesn’t rely on falsifying data to hit you in the face: instead, you’re actively looking for it. I’ve been trying to add more explicit experiments to my validation process.

If you’re interested in joining Complice when it becomes more widely available, head over to complice.co and enter your email address. My goal right now is to have something ready for New Year’s Resolution season, but given that I’m going to be busy with family stuff over the holidays, that’s going to be challenging!

This post adapted from the first entry into my business journal. I decided just today that it would be valuable, for myself and potentially others someday, to write for a few minutes at the end of most days with how things are going with my business. The intention is to capture the nuances and feelings that don’t show up in the list of things I did.

So there’s a thing called Crocker’s Rules which is rather popular in my network. At any time, one can declare to be operating by these rules, a declaration that constitutes a commitment to being fully open to feedback that isn’t couched in social niceties etc. The idea is it’s supposed to be a much more efficient/optimal way to communicate things. To me, Crocker’s Rules seem like a high ROI hack for getting certain things that I like about deep trust.

From the canonical article:

Declaring yourself to be operating by “Crocker’s Rules” means that other people are allowed to optimize their messages for information, not for being nice to you. Crocker’s Rules means that you have accepted full responsibility for the operation of your own mind – if you’re offended, it’s your fault. Anyone is allowed to call you a moron and claim to be doing you a favor.

First we need to ask ourselves what we mean by being “offended”. One of my all-time favorite articles is titled Why I’m Not Offended By Rape Jokes, and its opening paragraph reads:

I am not offended by rape jokes. Offended is how my grandmother feels if I accidentally swear during a conversation with her; the word describes a reaction to something you think is impolite or inappropriate. It is a profoundly inadequate descriptor for the sudden pinching in my chest and the swelling of fear and sadness that I feel when someone makes a rape joke in my presence.

So sure, I think declaring Crocker’s Rules includes relinquishing the right to claim someone said something impolite or inappropriate. It also means giving someone the benefit of the doubt around them being inconsiderate. However, there are lots of potentially cruel things they could say, and I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect those not to hurt.

People sometimes talk about Radical Honesty, a policy which is easy to confuse for Crocker’s Rules (though they’re kind of the opposite) and which can sometimes just come off as Not-that-radical Being-a-dick. There is a lot to be said for direct and open communication, but somebody who just says “you’re a moron” isn’t usually being helpful. Tact can be valuable: saying everything that’s on your mind might not actually help you or the other person achieve your goals. The brain secretes thoughts! Some of them happen to be totally useless or even harmful! [EDIT 2021: I would no longer say this so categorically. Read Dream Mashups for a better sense of how I’d talk about this now.] And, just like you don’t want to identify with unduly-negative self-judgements, not all thoughts about someone else are worth granting speech.

On a related note, I know someone whose contact page used to say something to the effect of “I operate by Crocker’s Rules, but I’m also an ape, so I’m likely to be more receptive to criticism if it is friendly.”

I want to touch on the question of efficiency. Are Crocker’s Rules optimally efficient as a communication paradigm? On an information level, theoretically yes, as it tautologically eschews adding extra information. On a meta-information level it is very efficient as well, as the act of declaring Crocker’s Rules is a very succinct way to communicate to someone else that you want to be efficient in this way.

However, there’s more to communication than information, especially when it comes to interpersonal dynamics. I talked about this in my post on feedback a few months ago. Sometimes the feedback you most need isn’t efficient. Sometimes it’s vague and hard to express clearly in just a few words, and would become garbled in the process. Sometimes the feedback is a feeling. It’s saying “when I experience you doing X, it makes me feel Y.” And this requires vulnerability on the part of the person giving the feedback, which can’t be caused by any amount of you self-declaring Crocker’s Rules. For that, you need trust.

In the short-term, trust-based communication can be incredibly slow. I thought of using an adverb like “excruciatingly” there, but I actually find it very pleasurable. It’s just frustrating if you’re in a rush. In the long-term, however, building trust allows for even more efficient/optimal interactions than Crocker’s Rules, because you have a higher-bandwidth channel.

I believe that the primary useful function of Crocker’s Rules is in acute usage, such as soliciting honest general feedback or soliciting any kind of feedback really. Mentioning Crocker’s Rules in such a context is very effective shorthand for indicating that you want all of the grittiest, most brutal feedback the person is willing to offer, not just surface stuff or “grinfucking“. The article doesn’t have a quotable definition for that term, but it’s essentially giving someone bland positive feedback when your honest feedback would be strongly negative. You’re grinning at them but in the long-run the lack of honest feedback is fucking them over.

To me, Crocker’s Rules seem like a high ROI hack for getting certain things that I like about deep trust. I think its ultimate form would in fact be a kind of trust: a trust that the other person fundamentally has your best interest in mind. However, we often can’t reasonably have that trust yet in many contexts in which we’d like honest feedback. Hence approximations like Crocker’s Rules.

“Implementation Intentions” is a tool from psychology literature that has been conclusively shown to increase the tendency of people to actually carry out actions towards their goals. Feel free to read the paper if you want justification. Since there’s plenty of that and I’d be just copy-pasting the article, I’m going to focus on the application side.

You can use this for huge goals or things you’re trying to accomplish, or it could just be a simple habit you want to create/change/eliminate. One example that’s worked well for me is staying up when I get up. I don’t have a big issue with getting up when my alarm goes off, but if I’m at all tired or even just cold, I feel a strong inclination to just crawl back into my nice warm bed… but when I do that, I fall asleep, and it usually isn’t even particularly restful sleep. So my goal here is to stay out of bed once I’ve gotten up.

This technically isn’t part of implementation intentions either—but it’s another well-documented tool that helps with goal success and that works well with implementation intentions. Warning: there are two key parts here that must be combined. Doing both will increase your chance of success; doing only one will decrease it.

The first part is to spend some time thinking about the benefits of achieving your goal: the short-term peace of having a relaxed morning instead of a rushed one… the long-term time gained by not oversleeping, and the value of whatever I spend that time doing instead. The second part is to bring to mind all of the obstacles you can think of, ranging from the regular and simple (“I get cold” or “I get tired”) to the less frequent and complex (“someone else is in the bathroom”).

Here’s what mine looks like for up-getting:`

Benefits:

Obstacles:

What’s key, the research reveals, is to then contrast those obstacles with the ultimate benefits, so that you get a clear association in your mind that those things are what’s standing in the way of you having all of that awesome success. Once you’ve done that…

In the case of getting up, there’s really only one main opportunity: when I hear my alarm clock. Motivational speaker Zig Ziglar actually likes to refer to this device as an “opportunity clock” because he thinks it’s a helpful positive reframe. “If you can hear it, you’ve got an opportunity.”

For a goal like “exercise more”, there are many opportunities. One in each context where you’re choosing what to do with your body. Perhaps when you decide whether to drive or bike to work, or to take the elevator or the stairs. Is there a bar somewhere in your daily routine that would be great for pull-ups? What would be a convenient time and place to do some crunches?

If you’re a programmer, then this will be really familiar. If not, then this sentence and the previous one are sort of examples. If-then statements are the core of implementation intentions. The name itself is to contrast with what researchers call “goal intentions”. Goal intentions are things like “I intend to be 10lbs lighter in 3 months” or “I intend to write a 50,000-word novel by the end of November.”

Implementation intentions look more like “if I have the chance to eat a cookie, then I’ll just take a deep breathe and refuse the cookie” or “if I sit down at my computer, I’ll open up the draft of my novel and write at least 1000 words before I go on Facebook”.

Goal intentions, despite having little directly to do with behaviour, have been shown to be effective for producing behaviour change. With implementation intentions and mental contrasting, they become even more effective. To create your if-then statements, start with the opportunities you identified in step 3. This is the initial “if” part. Then, add the intended action in those circumstances.

This is what I started with:

• When I hear the zeo opportunity clock, then I’ll get up and turn it off

It helps to be specific so that your brain is really certain when the “if” is triggered. I actually started with something I almost always do anyway. I then added:

• If I’ve just turned off the zeo, then I’ll go to the bathroom and weigh myself [I’m tracking my weight on beeminder]

This helps to create a new habit at that decision point where I’m deciding whether or not to go back to bed. While these two lines would be better than nothing on their own, they actually still have substantial room for improvement. Brains are incredibly skilled at generating excuses for things that are unpleasant or inconvenient or even just unfamiliar. You need to catch those cases. This was the ultimate chain of If-Thens that I created:

• When I hear the zeo opportunity clock, then I’ll get up and turn it off

• • If I’ve just turned off the zeo, then I’ll go to the bathroom and weigh myself

• • • If I feel like going back to bed instead, then I’ll ignore that feeling and still go weigh myself

• • • If someone is in the bathroom, then I’ll stay standing and start my morning intentions

• • • If I still feel tired, then I’ll go to the kitchen, get water, and splash it on my face

• • • • If I’m not dressed, then I’ll put on sweatpants then go

• • • If I realize that somehow I’ve sat or laid down on my bed, then I’ll count from 5 down to 0 then stand up on zero [this helps in tired situations because it doesn’t feel effortful to start counting]

• After weighing myself, then I’ll start my morning intentions

• • If I feel like doing them in bed, then I’ll do them sitting at my desk instead

Note that in several cases the “if” is basically “if I don’t feel like it”. While this might be surprising, or seem silly, it’s actually really key. If you say, “I’m going to go to the gym on Monday” then you’re implicitly assuming that on Monday you will still want to go to the gym. If you don’t, your brain might assume that you therefore don’t need to go. If, however, you decide that even if you don’t feel like it, you’re going to go anyway, then that excuse doesn’t work anymore.

This won’t come as a surprise to anyone who’s ever heard someone say “I’m never gonna drink again” …more than once. Turns out that not only does that not work, but it backfirefs, in the same way that trying not to think of a white bear usually results in frosty ursine thoughts. So rather than focus on the behaviour you want to avoid, think about what you want to do instead. I know if I heard someone say “from now on, I’m only drinking soda at parties!” I might actually expect them to succeed.

Start with implementation intentions for something that feels challenging but not overwhelming. Then you’re likely to succeed, after when when you add a new layer to this (either in the original goal or for a new one) you’ll already think of it as an effective system, and one that you obey.

This post explains success spirals really well.

blog.beeminder.com/nick

If you set up your Implementation Intentions so that you’ve eliminated all snacking from your life with this, but you still want to snack sometimes, then you’re going to be forced to break your intentions to do so, which sets a precedent you don’t want. Instead, you might try something like what I did:

– If I really want a snack and I haven’t had one that day, then I can trade a coupon for a snack, provided that coupon was created at least a day ago.

I would just write eg “Friday Snack Coupon” on a sticky note on Thursday, and then on Friday I could buy a snack with this. This way I could still snack in a very limited way without breaking the official contract I’d set with myself.

One last tip—I know this is a lot! This whole thing doesn’t work if you find yourself in this situation and you don’t remember what your if-then actually was. There are two things that can help with this: first, start with simple If-Thens that are fairly easy to remember. Secondly, just create a global catchall If-Then:

• If I find myself in a situation where I’m pretty sure that I have an implementation intention but can’t quite seem to recall what it was, then I’ll behave in a way that seems like the kind of thing I’d put for the Then section in this context.

I just came up with that right now, so I’ll have to give it a field-test and see if it works.

Complice is launching soon.

What do people think of you? What affects what people think of you? I’m realizing that if you focus on what people think of you this moment, you usually lose track of what they’re going to think of you next month.

I’m interning at a large tech company for the first time (previous max was a 22-person startup) and I’ve been having some trouble navigating how to ask questions and get things done in the rather complicated system. Today, in my 1-on-1 meeting with my manager, we were talking about asking others for help, which he pointed out is really important in a large organization with relatively little documentation. I commented that I was worried that people would feel like I was asking them to solve all of my problems—that they might judge me for doing so. I described one part of this problem using this analogy:

Say I’m trying to make myself a sandwich, and I don’t even know where the bread is kept. So I ask you, “where’s the bread?” You indicate the appropriate cupboard. Then I get distracted for half an hour, initially trying to choose a kind of bread but then reading the ingredients… after which I find the knife and realize it’s totally dull and won’t slice the bread (the next step).

At this point I feel really apprehensive about asking you for help again, because I feel like you’ll notice how I haven’t really accomplished anything for awhile (with software development, this can be more on the order of hours and days) and that I’m now asking you for help with something that’s basically a next step to the last thing I asked about. Or that could be expected to follow within 2 minutes.

“Don’t worry about what people think of you,” my manager responded, to this story and to other concerns about pestering people, “think about the results.” In other words, if you’re hungry, do what it takes to get that sandwich made. Then it dawned on me that by trying to avoid having people think negatively toward me in the short term by asking too many questions, I was ultimately sacrificing their long-term opinion of me by reducing what I was able to accomplish.

When I’m finishing my internship, I’d much rather have a couple of people think, “Oh yeah, Malcolm was great, though he asked a lot of questions,” than have everyone think, “Malcolm just kind of went off on his own and barely accomplished anything”. Which is sillifying to realize, because I haven’t been behaving with that in mind. Well, it’s hard to change what you don’t even notice, so this is a start.

I wrote the bulk of the above this afternoon in an email to myself (something I do with surprising regularity) and then thought I’d share it on my blog, for a few reasons, notably that it’s a great example of conflicting wants. There’s a deeper shift happening here too, which is the realization of how my concern over my own image is itself getting in the way of both image and goals, therein being quite unproductive. But for now it seems easier to shift on the level of behaviour->values, achieving them in the short term rather than trying to change my values overnight.

I write a lot about goals. Sometimes big meaty well-defined goals like the album I recorded last year or the polyphasic experiences I had this summer. Other times the goal is just a 30-day challenge to do something daily or give something up. Sometimes it’s more abstract, like my aspirations to become more aware of my own mental processes. In the past few weeks, I’ve started taking things to the next level in a few ways. First, I’ve started doing not just evening reviews but also morning solo-standups where I plan my day. Second…

I’ve started a business to help other people with their goals.

I’m running this business incredibly lean:

I don't think I understood the concept of "lean" until I had three paying customers for a business that doesn't have a name yet.

— Malcolm Ocean (@Malcolm_Ocean) October 1, 2013

About 2 weeks ago, I was reflecting to my friend Dan from Beeminder about how I thought I might be able to create something to play a kind of complementary role to his product. While Beeminder helps you keep track of numeric goals, I found I needed another system to help me keep track of my progress on more abstract and nuanced goals. As I noted during my end-of-2012 reflection, last year I started using the Pick Four system by Seth Godin and Zig Ziglar. Naturally, of course, as a tinkerer, I was constantly tweaking it, and developed a more robust system. I also found myself wishing I had better software to help me keep track of everything.

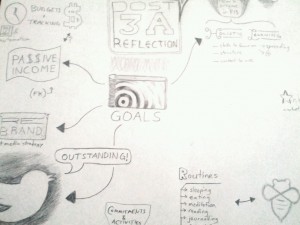

This summer I tried doing sketchnote style goal planning. Really pretty but didn’t actually help much.

However, I figured, it probably wouldn’t be worth it to build that kind of software just for myself. Would it be valuable to others too? Dan recommended starting just the way he started Beeminder: by helping one friend, manually. By chance, later that day I found such a friend, and so after talking with him briefly about his goals, we started going through the steps of the system. I would email him questions and prompts inspired by Pick Four, and he would respond. Meanwhile, I was also pitching the idea to other friends and getting them to sign on for my beta, which I’m hoping to start with about a dozen people in November.

…about a dozen people, who have some goals they seriously want to achieve, and are feeling frustrated because they feel like they aren’t making as much progress towards them as they’d like. If this sounds like you, let me know! If you’re not sure if it’d be a good fit, get in touch and we’ll have a quick Skype chat. [EDIT 2013-11-05: the beta cohort is now closed, but feel free to email me and I’ll keep you posted]

So far the November beta cohort is about half-filled. At that point, things will be a bit more streamlined, although people will still be interfacing with me regularly—once this really gets running, in 2014, it’s going to be mostly automated, so if you want the chance to have a really cheap personal goals coach (me!) then now’s the time. The beta is going to be $10/month; after that the service is probably going to be at least twice as much. While I charge separately for full-on consulting, it’s super important to me that my system is helping you, so if you’re stuck then I’ll gladly help troubleshoot things with you. My business doesn’t have a name yet, but I think it will be valuable for people. Full refund offered if it isn’t—I want my customers to be satisfied.

I’m spending this upcoming weekend mentoring at the October CFAR workshop, where I hope to pick up some new ideas for what kinds of questions will help people most with staying on track, and to have more chances to pitch my business to smart, ambitious people.

I’m giving up gluten for a month. Maybe longer.

Many of my earliest posts on this blog are about my 30-day challenges: behaviour changes I undertake for a month. I’ve been on a hiatus for awhile, which initially was for the purposes of installing some new habits but then later was just because I forgot to restart.

Last week at work, I realized that I’d nearly stopped eating gluten. The cafeteria at Twitter (where I’m interning for my penultimate co-op placement) has a lot of very healthy food, including grass-fed beef and many gluten-free options. Since I try to eat a kind of “relaxed paleo”, I gradually started eating fewer and fewer of the dishes containing gluten. I haven’t been a huge fan of bread for years, so this was a fairly easy transition to make.

I hear, however, that for many people the biggest changes result not from severe reduction of gluten intake but from complete elimination. This is obviously true for those with coeliac disease or a wheat allergy, but various bits of evidence (google for this if you care) suggests that there’s a decent probability of having some effect occur for me anyway. New models suggest that there’s a spectrum of gluten sensitivity.

At any rate, since this is an relatively very easy experiment for me to perform right now, with potentially very valuable results, it seems like something worth doing. I’ll decide later in the month if I want to continue being gluten-free or not. It strikes me that most gluten-sensitive people notice a pretty sudden and dramatic effect when they start consuming it again, so maybe I’ll do that just as a further experiment.

The official box for my Gluten-free Challenge:

Small text: I will try very hard to avoid products that say “may contain traces”. I’m going to disprefer products made in the same factory as gluten, but not avoid them outright. I reserve the right to drop this challenge in life-or-death / starving situations.