Sixth post in “I can tell for myself” sequence. On the last episode… Reality distortion: “I can tell, but you can’t”, which opened up our exploration of interactions between one person who is in touch with their own direct-knowing and another person who is more just taking others’ word for it. With this post we’re finally reaching some of the core ideas that the other posts have been a foundation for.

(I left “guru” in the title of this part, because “guru dynamics” are what I call this phenomenon, but I decided not to use the word “guru” in the body of the text. It’s a loanword that originally means “teacher” but of course in English has the connotations associated both with spiritual teaching in particular and thus also with the dynamics I want to talk about here, some of which are well-documented in The Guru Papers. To be clear, I don’t think guru’ing, as a role, is necessarily bad—it’s just extraordinarily hard to do well. But “guru” as a frame… the roles are probably best not thought of as a student-teacher relationship at all. Instead, perhaps, “one who’s remembering” and “one who’s reminding”: ancient wisdom tradition words for this like “sati”, and “aletheia” mean “remembering” or “unforgetting”. Those are awkward though.)

Things get weird when a person who has consistent access to their sense of “I can tell for myself” across many domains—especially spiritual, interpersonal, esoteric, subtle, ineffable., ones—finds their way into a position where they’re trying to help others develop this capacity for themselves.

This happens remarkably often! There are many factors that contribute to this, of which here are six:

So it’s very common for someone who has developed their sense of self-authored direct-knowing to find themselves surrounded by a bunch of people who also want to develop this capacity. (We’ll explore in a later post why there’s often precisely one teacher per learning context; the previous post also hints at it.)

But attempting to teach “I can tell for myself” (or self-trust, or whatever you call it) leads to what is nearly a paradox:

Suppose that when someone says something you don’t understand or resonate with, your two available moves are either to reject what they’re saying or “take their word for it”—a condition which is tautologically the starting point for someone who has learned to not trust themselves in the face of what someone else is saying, and is wanting to develop that self-trust—then if I’m trying to convey “how to tell for yourself”, you’ll either… reject what I’m saying as senseless, or… take my word for it that this is in fact how to tell for yourself and you just need to do it exactly as I say yessirree!

…which is not “I can tell for myself”. Or is it?

» read the rest of this entry »“I can tell for myself” is the kind of knowing that nobody can take away from you.

Nobody can take it from you, but they can get you to hide it from yourself. They can put pressure on you to cover up your own knowings—pressure that’s particularly hard to withstand when you’re relatively powerless, as a kid is. This pressure can come from the threat of force or punishment, or simply the pain of not being able to have a shared experience of reality with caregivers if you know what you know and they don’t allow such a knowing.

Ideally, we integrate others’ word with our own sense of things, and smoothly navigate between using the two in a way that serves us and them. Others would point out where they can see that we’re confused about our own knowings, and we’d reorient, look again, and come to a new sense of things that’s integrated with everything else.

But, if you’re reading this, you were probably raised in a culture that, as part of its very way of organizing civilization over the past millennia, relied on getting you to take others’ word for it even when you could tell that something about what they you being told was off… to the point that you probably learned that your own knowing was suspect or invalid, at least in some domains.

Did you cover up your natural sense of appetite, with politeness, when parents or grandparents said “You haven’t eaten enough! You have to finish what’s on your plate.”? Did you cover up your natural sense of thirst when parents or teachers said “No, you don’t need a drink right now.”? Did you forget how to listen to the building pressure in your lower abdomen, in the face of a “You don’t have to pee! You just went!”?

Did you override your sense of relevance and honesty when someone said “You can’t say that!”? Maybe someone close to you said “You didn’t see that!” or “you didn’t hear that!” or “that didn’t happen!” — as a command, not a joke… did that make it harder to listen to your own senses or vision or hearing? Not altogether, but in situations where you could tell others wouldn’t like you to know what you know. Did someone say “Come on, you know I would never lie to you,” twisting your own sense of trust in others’ honesty and dishonesty, around the reality that you did not, in fact, know that, and (since this was coming up at all) may have been doubting it?

Or more straightforwardly:

“how to give feedback to somebody about something that you’re noticing going on for them, where you suspect that if you try to acknowledge it they’ll get defensive/evasive & deny it”

One of the core principles of my Non-Naive Trust Dance framework is that it’s impossible to codify loving communication—that any attempt to do so, taken too seriously, will end up getting weaponized.

Having said that, maybe if we don’t take ourselves too seriously, it would be helpful to have a template for a particularly difficult kind of conversation: broaching the subject about something you’re noticing, where you expect that by default what will happen is that you won’t even be able to get acknowledgement that the something exists. This can be crazy-making. I often call it “blindspot feedback” although for most people that phrase carries connotations that usually make people extra defensive rather than more able to orient and listen carefully.

To see more about how I think about this, you can read this twitter thread:

But I want the template to stand alone, so I’m not going to give much more preamble before offering it to you. The intent is that this template will help people bridge that very first tricky step of even managing to acknowledge that one person is seeing something that the other person might not be seeing, and having that be okay.

I’m calling this alpha-testing not beta-testing because while I know the principles underlying this template are sound, and I’ve tested the moves in my own tough conversations and while facilitating for others… as of this initial publication the template itself has been used zero times, so I don’t want to pretend that it itself is well-honed.

So I’d like to collect lots of perspectives, of what people think of the template just from looking at it, and of how conversations go when you try to use the template for them.

Without further ado, here’s a link to the template.

I’d love if you gave me your thoughts while you read it. To do that, make a copy, name it “Yourname’s copy of Template” then highlight sections and leave comments on them, then give comment access to me (use my gmail if you have it, or malcolm @ this domain). That would be very helpful. Even just little things like “ohhhh, cool” or “I don’t get why you’d say this” or “would it work to rephrase this like X, or would that be missing something important?”

To try it out, make a copy, then fill it out, and do what you want with it. Then, if you’d like to help me iterate on it or would otherwise like your experience of using it seen by me, fill out this form and let me know how it worked for you (or didn’t).

I’m back in the bay area for the first time in awhile

this has involved seeing some folks that I haven’t seen in a long time (4-6 years)

in a few cases, these were people that I was quite close to years ago (more like 7-8 years)

well, when I say close, I don’t necessarily mean emotionally close. but we had conversations, worked on projects together, and talked about important things

important things like the end of the world

important things like what we were supposed to do about the end of the world, and how to think about the end of the world, and how we were supposed to feel very scared and very determined to do something about it

and there were two people who, in order to be honest in encountering them again, I had to acknowledge that we had some reconciliation to do. it was scary but utterly necessary to say. any change of heart unacknowledged produces subtle weirdness. distrust unacknowledged makes it harder to get shared reality

as I wrote in 2021: Catching my Breath, I’ve done a bunch of healing over the past years about ways in which I was applying a kind of pressure on myself that made it hard to rest. physiologically I had a sense that there was something not right, something I needed to fix, something not okay about the world.

and I feel like my internal pressure has largely eased off. not that there isn’t more to untangle—I’m sure there is—but overall it feels quite integrated

thus in encountering these old acquaintances, I didn’t have a sense of needing something from them, for my own wholeness. but I needed to have a conversation about it in order to for the two of us to have wholeness, and by extension, for the larger community we’re part of to have wholeness.

I’ve been practicing confronting people, to acknowledge past boundaries crossed, even when there’s nothing to be done about it at this point. It’s really profound, just to have my anger heard and received—to have the loop closed. something laid to rest. I did a bit of that with my parents last fall.

in the first case, you arrive midafternoon, and you see me in the co-what-now corner and come over to talk. you start to just dive in with me about something interesting and timely and quite personal, and I’m finding myself needing to just slow down and acknowledge the tension from years past. you seem disappointed locally by the interruption, but overall appreciative that I’m naming it, and unsurprised to hear that it’s there. we agree to talk about it later. you ask if it’s okay that I don’t trust you, observing that in some sense it seems it might not be, and I say I’ll ponder that. I muse to myself that maybe there’s something in you that feels not okay with it, that is splitting and afraid of being tarred as plain bad.

» read the rest of this entry »For its whole existence, I’ve been vaguely wanting my business to grow. For a while, it did, but for the most part, it hasn’t. I wrote last post about how I have increasing amounts of motivation to grow it, but motivation towards something isn’t enough to make it happen. You also need to not have other motivations away from it.

My understanding of how motivation & cognition works is that any inner resistance is a sign of something going unaccounted for in making the plan. Sometimes it’s just a feeling of wishing it were easier or simpler, that needs to be honored & welcomed in order for it to release… other times the resistance is carrying meaningful wisdom about myself or the world, and integrating it is necessary to have an adequate plan.

In either case, if the resistance isn’t welcomed, it’s like driving with the handbrake on: constant source of friction which means more energy is required for a worse result.

Months ago, I did a 5 sessions of being coached by friends of mine as part of Coherence Coaching training we were all doing. Mostly fellow Goal-Crafting Intensive coaches. My main target of change with this coaching was to untangle my resistance to growing Intend. I think it loosened a lot of it up but I still have work to do to really integrate it.

In this post, I’m going to share some of the elements I noticed, as part of that integration as well as working with the garage door up and sharing my process of becoming skilled at non-coercive marketing. Coercion is quite relevant to some (but not all!) of the resistance I’ve found so far.

I’m going to do my best to be more in a think-out-loud, summarize-for-my-own-purposes mode here, rather than a mode of presenting it to you. Roughly in chronological order by session, which happens to mostly start by looking at money and end by looking at marketing…

This isn’t one I have very strongly, but it did arise a little bit. There was a sense of I don’t want to have too much money because then people will want my money. (Interestingly, time doesn’t work like this since it’s not so fungible in most cases!) But overall I like being generous and I expect that if I suddenly had a bunch of people trying to get me to contribute to their things, I’d do a good job of figuring out how to manage that. And frankly probably lots of people I know have likely assumed that I have more money than I do and I haven’t received the slightest pressure related to that (although a couple people over the years asking if I’d angel invest, which is the kind of message I’d like to get from friends anyway!)

» read the rest of this entry »What’s the difference between positive & negative motivation?

I like to talk about these as towardsness & awayness motivation, since positive & negative mean near-opposite things in this exact context depending on whether you’re using emotional language (where “negative” means “bad”, ie “awayness”) or systems theory language (where “negative” means “balancing” ie “towardsness”). I have a footnote on why this is.

There’s a very core difference between these two types, both inherently to any feedback system and specifics to human psychology implementation.

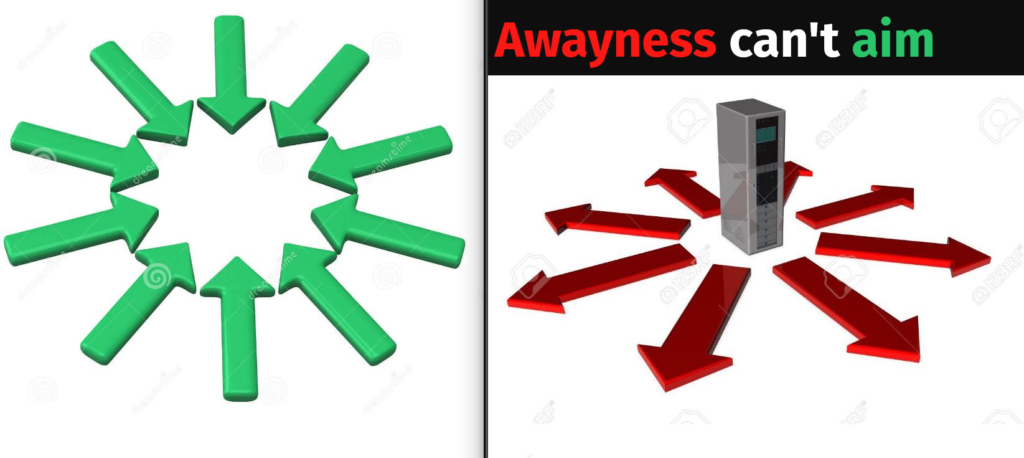

Part of the issue is (and this is why I say positive vs negative motivation are different in all systems) you fundamentally can’t aim awayness based motivation. In 1-dimensional systems, this is almost sorta kinda fine because there’s no aiming to do (as long as you don’t go past the repulsor). But in 2D (below) you can already see that “away” is basically everywhere:

Whereas with towardsness, you can hone in on what you actually want. As the number of dimensions gets large (and it’s huge for most interesting things like communication or creative problem-solving) the relative usefulness of awayness feedback gets tiny.

Imagine trying to steer someone to stop in one exact spot. You can place a ❤ beacon they’ll move towards, or an X beacon they’ll move away from. (Reverse for pirates I guess.)

In a hallway, you can kinda trap them in the middle of two Xs, or just put the ❤ in the exact spot.

» read the rest of this entry »It’s now been five years since I first attended a CFAR workshop. I wrote a 3-year retrospective 2 years ago. Today I want to reflect on one specific aspect of the workshop: the Againstness Training.

In addition to the 5 year mark, this is also timely because I just heard from the instructor, Val, that after lots of evolution in how it was taught, this class has finally been fully replaced, by one called Presence.

The Againstness Training was an activity designed to practice the skill of de-escalating your internal stress systems, in the face of something scary you’re attempting to do.

I had a friend record a video of my training exercise, which has proven to be a very fruitful decision, as I’ve been able to reflect on that video as part of getting more context for where I am now. Here’s the video. If you haven’t seen it, it’s worth watching! If you have, I recommend you nonetheless watch the first 2 minutes or so as context for what I’m going to say, below:

How do you know that you’ve been understood?

This question is one I think about a fair bit, and part of what motivated me to write the jamming/honing blog post.

If I’m saying something something really simple and hard to misunderstand, all I basically need to know is that the message was received and the listener isn’t confused. for example “Hey Carla, I left the envelope outside your room.” If Carla says “OK” then I can be pretty sure she’s understood. (Unless of course she misheard me saying something else reasonable.) A slight modification of this would be a situation where the information is straightforward but detailed—and the details matter. In these situations, often the entire message is recited verbatim. A classic example would be when a number is spoken over the phone, and the listener echoes each set of 3-4 digits.

But when communicating something more complicated or nuanced, it’s usually not enough for the speaker to just get a “K” in response. If I’m trying to convey a model to you, one common way for us to verify that you’ve understood the model is for you to say something that you would be unlikely to be able to say if you hadn’t. This could take the form of explaining the model in a new way: “ahh, so it’s kind of like Xing except you Y instead of Z” or it could involve generating an example of something the model applies to.

I think we do this intuitively. Responding to an explanation with “K” potentially implies a lack of having engaged with the details. More like “You’ve said some things and I’m not arguing with them.”

On the International Space Station, the American astronauts would speak to the Russian cosmonauts in Russian, and the Russians would reply back in English (source). The principle is that it’s much easier to tell if someone has your language confused than it is to tell if you’ve correctly interpreted something in a foreign language.

I wrote a post last year on two different kinds of expectations: anticipations and entitlements. I realized sometime later that there is a third, very important kind of expectation. I’ve spent a lot of good time trying to find a good name for them but haven’t, so I’m just calling them “the third kind of expectation”. On reflection, while this is unwieldy, it is an absolutely fantastic name by the sparkly pink purple ball thing criterion.

First, a recap on the other two kinds of expectations in my model: anticipations and entitlements. An anticipation is an expectation in the predictive sense: what you think will happen, whether implicitly or explicitly. An entitlement is what you think should happen, whether implicitly or explicitly. If your anticipation is broken, you feel surprised or confused. If your entitlement is broken, you feel indignant or outraged.

I made the claim in my previous article that entitlements are in general problematic, both because they create interpersonal problems and because they’re a kind of rationalization.

Since then, some people have pointed out to me that there’s an important role that entitlements play. Or more precisely, situations where an angry response may make sense. What if someone breaks a promise? Or oversteps a boundary? It’s widely believed that an experience of passionate intensity like anger is an appropriate response to having one’s boundaries violated.

I continue to think entitlements aren’t helpful, and that what you’re mostly looking for in these situations are more shaped like this third kind of expectation.

Another personal learning update, this time flavored around Complice and collaboration. I wasn’t expecting this when I set out to write the post, but what’s below ended up being very much a thematic continuation on the previous learning update post (which got a lot of positive response) so if you’re digging this post you may want to jump over to that one. It’s not a prerequisite though, so you’re also free to just keep reading.

I started out working on Complice nearly four years ago, in part because I didn’t want to have to get a job and work for someone else when I graduated from university. But I’ve since learned that there’s an extent to which it wasn’t just working for people but merely working with people long-term that I found aversive. One of my growth areas over the course of the past year or so has been developing a way-of-being in working relationships that is enjoyable and effective.

I wrote last week about changing my relationship to internal conflict, which involved defusing some propensity for being self-critical. Structurally connected with that is getting better at not experiencing or expressing blame towards others either. In last week’s post I talked about how I knew I was yelling at myself but had somehow totally dissociated from the fact that that meant that I was being yelled at.