…when to correct and when to riff…

Say you’re having a conversation with someone, and you’re trying to talk about a concept or make sense of an experience or something. And you say “so it’s sort of, you know, ABC…” and they nod and they say “ahh yeah, like XYZ”

…but XYZ isn’t quite what you had in mind.

There can be a tendency, in such a situation, to correct the person, and say “no, not XYZ”. Sometimes this makes sense, othertimes it’s better to have a different response. Let’s explore!

The short answer is that this sort of correction is important if it matters specifically what you meant. Otherwise (or if this is ambiguous) it can frustrate the conversation.

The most extreme example of where it feels like it matters is if you have a particular thing in mind that you’re trying to explain to the other person—like maybe someone is asking me to tell them about my app, Complice:

Me: “It’s a system where each day you put in what you’re doing towards your long-term goals, and track what you accomplish.”

Them: “Ohh, so like, you use it to plan out projects and keep track of all of the stuff you need to do… deadlines and so on…”

Me: “Ahh, no, it’s much more… agile than that. The idea is that long-term plans and long task lists end up becoming stale, so Complice is designed to not accrue stuff over time, and instead it’s just focused on making progress today and reflecting periodically.”

Where the shared goal is to hone in on exactly how Complice works, it makes sense for me to correct what they put out.

We might contrast that with a hypothetical continuation of that conversation, in which we’re trying to brainstorm, or flesh out an idea:

Me: “Although I’ve been trying to figure out how maybe I could add more future-planning to Complice, without it becoming stale…”

Them: “Hmm, so I guess things go stale because you don’t go back to update them…”

Me: “Right, yeah. I’ve been thinking about it as more of a ‘how can I automatically prevent it?’ but maybe you could also make it be like, ‘how can I entice people to go back and update their plans?'”

So again, the thing the person puts out in line 2 is not quite what I’m thinking about (as I state in the dialogue). But here, the shared goal is to figure out together what this staleness thing is and how it works, so in line 3, I explore that. We’re trying to build up an understanding together, and for me to just say “no, that’s not what I’m thinking” would basically imply that I’m just using them as a sounding board and I’m not open to hearing their perspective.

Speaking of hearing someone’s perspective, though, sometimes in that situation you do want to correct, so you can hone in on their experience.

Them: “Yeah, and I think like, when I think of my old plans, I don’t want to look at them because I know that they’re really bad…”

Me: “Oh, so it’s like, then you feel ashamed that they aren’t better?”

Them: “No, it’s more like a messy room—it’s kind of overwhelming and I don’t know where to even start trying to make it better.”

Here, within the shared goal of grokking staleness, we have a shared subgoal of understanding what this person’s experience is of being averse to revisiting old plans. So if I posit that maybe it’s shame-related, and they introspect and feel like it isn’t, then I want to be corrected!

So it’s clear from the dialogue above that there are two patterns of interaction here, both of which are valuable. How might we describe the distinction?

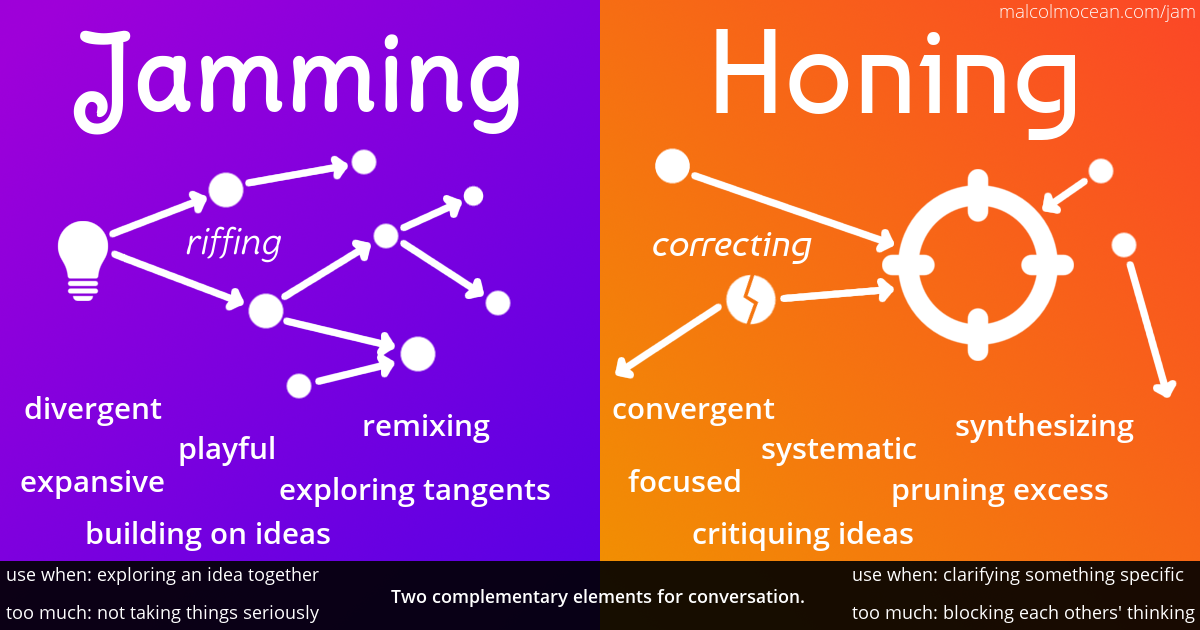

One metaphor I really like comes from music. I’ve used the word “hone” several times in this essay, and it captures one mode well, covering both the idea of converging on a target and the idea of sharpening something. If we’re making music together, this is like practising so that we’re totally in sync, or perhaps it’s someone trying to teach someone else a particular piece. Let’s call this Honing Mode, and the main verb it has is correcting.

The alternative way of making music together is jamming. While jamming is improvisational, it’s not that anything goes—you still need to play something that fits the rhythm of the music and that also makes sense given what the other person just played. But there’s no “right way”, or specific target, just an exploring of the space. In Jamming Mode, the main verb is riffing—taking what’s present and expanding on it.

I think that one reasons conversations break down is that these two dynamics aren’t in balance.

The failure mode where you have too much honing/correcting and not enough jamming/riffing looks like bad improv: people getting in each other’s way and not being able to create anything. Here’s Keith Johnstone talking about his experience teaching people about this:

I put the lists aside and get the students to play ‘shop’.

“Can I help you?”

“Yes, I’d like a pair of shoes.”

“Would these do?”

“I’d like another colour.”

“I’m afraid this is the only colour we have, Sir.”

“Ah. Well, perhaps a hat.”

“I’m afraid that’s my hat, Sir.”

And so on—very boringly, with both actors ‘blocking’ the transaction in order to make the scene more ‘interesting’ (which it doesn’t).

This is from Impro, a brilliant book. Even if you haven’t done improv, you probably recognize the experience of feeling like you can’t get anything through in a conversation, or that all of your attempts to connect seem to fall flat.

The alternate failure mode, where you have too much jamming and not enough honing looks like brainstorming gone wild: people are just suggesting ideas, and you end up with… a lot of ideas, but nothing is really landing. The ideas might be good, but people are starting to get a bit checked out and not feeling like they’re able to communicate the core of anything important. Each person is saying stuff loosely inspired by what each other is saying, but it’s unclear if they’re actually taking in each others’ ideas or just using them as scaffold or inspiration for their own. (I once witnessed a conversation among two stoned people that was very obviously this extreme.)

The original instructions for brainstorming come from Alex Osborn in 1942, and included a rule not to criticize others ideas. However, evidence suggests that this may not actually be very effective in practice. Disappointingly, we’ve known this for 50 years, and yet people still tout the old rules:

“The first empirical test of Osborn’s brainstorming technique was performed at Yale University, in 1958. Forty-eight male undergraduates were divided into twelve groups and given a series of creative puzzles. The groups were instructed to follow Osborn’s guidelines. As a control sample, the scientists gave the same puzzles to forty-eight students working by themselves. The results were a sobering refutation of Osborn. The solo students came up with roughly twice as many solutions as the brainstorming groups, and a panel of judges deemed their solutions more “feasible” and “effective.” “

— Groupthink: Jonah Lehrer for The New Yorker

The article goes on to cite a different study that found group creativity works best if you include a mix of “freewheeling”—making lots of suggestions without worrying about quality—and also debating—caring about the quality of what has been suggested, and trying to critique and improve it.

…much as I posited above.

FastCo has an article about a design consultancy called Continuum, and describes how they explicitly try to include a mix of the classic improv line “Yes, AND” and also “No, BECAUSE” which they consider the core motion of debate, or “deliberative discourse”, as they call it.

I think the the key point here is that there’s a huge difference between constructively debating against someone’s idea, and simply dismissing it. Taking the time to engage with what someone said, to understand it, and refute it, can be a way of showing respect for them bringing it up. Dismissing an idea without fully considering it isn’t really good jamming or good honing. “No, BECAUSE” is a decent simple practice for getting past that.

If people feel unsafe—if it feels like the relationship is at stake in a given conversation—that can create various interesting psychological challenges to thinking together.

One thing that can come up is a strong need to be understood—almost a paranoia of not being understood. This can create an inability to let someone else riff on your idea, because you’re afraid they haven’t actually grokked the core of it yet. So you’ll find yourself feeling their riffing is them not understanding, and you’ll try to correct them, but this will end up being blocky.

The complementary fear is that if your idea is criticized then that is a rejection of you as a person. This makes it scary to riff, because others’ corrections feel like they’re saying you have a problem. Here you get people trying to be creative and original, but feeling like they have to get it right the first time because otherwise they’re boring. And simultaneously, feeling threatened by what others come up with, creating an urge to reject such things regardless of their quality.

To some extent, these fears can be reduced by having basic group cultural norms such as the notion that sharing terrible ideas doesn’t make you a terrible person. But a lot of it is going to end up depending on the individuals and on the relationships (and past experiences) present in a given interaction. On the underlying sense of safety.

Unsafety can manifest in different ways, that might not always be easy to recognize. The book Crucial Conversations uses a two-part model:

When unsafe, people resort to either silence or violence.

SILENCE: purposefully withholding information from the dialogue.

– Used to avoid creating a problem.

– Always restricts the flow of meaning.

– common forms include masking, avoiding, and withdrawingVIOLENCE: convincing, controlling, or compelling others to your viewpoint.

– Violates safety by forcing [one’s own] meaning into the [shared] pool [of meaning] – common forms include controlling, labeling, and attacking.

What the authors of that book recommend is to step out of the content of the discussion, e.g. “whether or not to get a new car” and to get clear on the shared purpose of the conversation. This lines up well with my comments above that jamming and honing each make different kinds of sense depending on the shared purpose. Sometimes, people are reasonably able to navigate this naturally, but it helps to have some known tools in your kit for pointing at the desired experience of relating.

So here are two tools:

– Jamming Mode: divergent, playful, building on ideas, remixing, exploring tangents, expansive.

– Honing Mode: convergent, systematic, critiquing ideas, synthesizing, pruning excess, focused.

And you can balance between these modes not just between conversations, but every few sentences. I recommend installing a little trigger-action plan something like:

when I notice that my conversation is feeling a bit blocked or dead, I’ll pause and consider if I’m jamming where honing would be better, or vice versa. If it feels possible to simply switch, I’ll try that. Otherwise, I’ll try taking a step back and talking to the person on the meta-level.

This meta-level talking might be easier if you have a shared vocabulary to talking about your conversational dynamic and how it might be getting stuck:

Therefore, another recommendation I’ll make is to share this post with the people you relate to regularly, so that you’ve got this shared vocabulary. And be clear that that’s the purpose, otherwise they might feel like you’re trying to say “here, this article explains what you’re doing wrong.” Creating safety in relationships isn’t a one-sided thing.

Constantly consciously expanding the boundaries of thoughtspace and actionspace. Creator of Intend, a system for improvisationally & creatively staying in touch with what's most important to you, and taking action towards it.

クリス » 18 May 2016 »

Yessss, good job Malcolm, this is the stuff that makes me like your blog a lot!

As far as I can tell, this was fully your original thinking, based on template like: notice a pattern in your life, generalise, give it a name, think of ways to apply it to solve/improve something, expand until you get a reasonable length blog post.

I don’t care much about the expansion part – I can do that myself, and the post could well be 1/10th of the length with the same effective impact on me.

But the part with getting your models and concepts: I value it *a lot*.

You seem to have similar type of analytic insight and area of interest as me, but apparently it does not mean we get the *same* insights.

So more often than not, what you notice hits a hole between stuffs I’ve noticed by myself.

This makes me wonder about what is the optimal number of people thinking analytically about the area at hand (life/brains/people/doing stuff etc. in this case), and exchanging observations.

Too few would mean a lot of missed ideas, while too many – overhead to process duplication and communicate.

Seeing how your ideas often hit places where I haven’t looked too carefully, but also there is noticeable overlap, I’d noncommittally guess the number is 3 or 4.

In any case, keep doing the shit man.

– クリス / Kurisu / SquirrelInHell

Malcolm » 19 May 2016 »

Thanks 🙂

That’s basically the process haha! I’m actually surprised if you could have taken the basic distinction here and expanded it to include the nuances that I wanted to improve, including the parts about safety in relationships. What background context do you have to things like safety-in-relationships.

Do you have a blog, or somewhere where you share the insights you have? I’d be curious to read them 🙂

クリス » 20 May 2016 »

Hmm, no, I don’t think I could have come up with the same nuances as you. But I know that I can only make this stuff useful for me by coming up with my own nuances – customized to emotionally salient conversations that I remember now, and analyse in real-time using the new concepts later; and perhaps more importantly, nuances produced by my own thinking, which makes the whole thing “stick”.

I can briefly explain this part of the model I currently have of reading blog posts, however please keep in mind I have only mild confidence in it.

As good as reading about someone’s ideas is, there are pretty harsh limits to what you can *passively* learn.

I *know* that *you* consider the expansion that you wrote important, and *you* might think without it post would lose much of its value. This is caused by the expansion being perfectly fitted to *your* experience and life.

It might even *be* the more valuable part, but the point is moot. I’d guess that the expansion is mostly not learnable by other people, or at least not simply by reading it.

(A possible method to transfer the whole expansion to readers, could be to write a lengthy expansion of each part of the expansion?)

I’d put it like this: a blog post about an idea mostly serves these purposes:

1) communicate the core of the idea (a very basic version),

2) prove that the author considers the idea important, and has given it considerable thought,

3) set a lower bound on the time the reader’s mind is going to be focused on the idea (the time it takes to read through the post).

So, when I *already* respect someone’s way of thinking, I trust myself to need much less of 2) or 3). I suspect in many cases they might both be replaced with a simple “I think it’s valuable, so make sure you use whatever system you use to think about stuff, to think about this a lot”.

A more effective way of doing 3) is to have some live interactions with people, like discussing the idea with friends (or writing a comment).

Alternatively, I could think carefully about every part of what I read, from the people whose ideas I respect… if I already had high confidence in living >= 10000 years, that is…

Hmm, yup. Sounds about right as a description of what is out there. This is not the same as my opinion or reflective approval, though. Feel free to find problems with it.

And as for my own insights, well I tend to stick to the old fashioned talking to people (though I put a raw snapshot of one of my systems here -> https://squirrelinhell.github.io/ <- but no real descriptions, so kinda harsh to get something out of prbly?)

(In any case, I think I would enjoy talking to you on Skype or whatever, so if you happen to feel outgoing and adventurous drop me an e-mail, eh?)

– クリス / Kurisu / SquirrelInHell

Malcolm » 21 May 2016 »

> “It might even *be* the more valuable part, but the point is moot. I’d guess that the expansion is mostly not learnable by other people, or at least not simply by reading it.”

Hmm. This may be true for this post, inasmuch as the stuff around safety in relationships might be pretty hard to grasp without back and forth experiencing then making-sense-of-experiences with this lens… but it seems like by offering this lens in the post, even if people don’t immediately get it, it gives them a chance to get it later.

I think the very thing we’re talking about relates fundamentally to the honing/jamming thing. I feel a need to make the blog post very in-depth/expanded because otherwise I don’t feel confident that the people reading it are going to actually get the idea I’m putting out, and they might just say “well, it’s just divergent/convergent thinking”. And it’s related, but that’s not the point I’m trying to make.

Maybe I could be clearer in fewer words, but I dunno. Human brains are conducive to pattern-matching, and by extension pattern-botching. So it’s hard to actually say anything new and have it stick.

Yvonne Conybeare » 23 May 2016 »

Malcolm, thank you for this. Well-informed, observant and yes, new, as always. I love the terms you’ve come up with here. It seems the conversations you are addressing are work conversations, with an eye towards problem solving and productivity.

Yes, choosing “honing” can move things along when one person has a firmer grasp of what the agreed-on point of a conversation is, and 2. jamming, with the inclusion of “no because,” keeps jamming and riffing focused and productive when it’s agreed taking in something new is a worthy thing to do at this stage of development of an idea, before honing it or tossing it.

And yes, it would be good to know someone who already feels safe enough to believe you are not trying to say “here, this article explains what you’re doing wrong.” And I’d like to mention, if you have such people in your life, you’re already long in productive conversation partner stock, and these ideas will add even more value.

I believe though, that status-battle in the Johnstone sense (the need to assert and protect your sense of importance and identity parts of the larger need to be understood) is more likely to rear it’s mischievous and often ugly head in conversation between strangers, or co-workers who have not-matching ideas about communication (yet, hopefully), or family members with as much baggage as you have, that you speak with often.

Conversation with strangers and family is far more challenging than with the conversation partners you can forward this blog to, because either honing or jamming can be seen as status-grabbing moves if there isn’t already agreement about what the point of a conversation is! Friends, or people who share values or workplaces tend to get to agreement on “the point” early on. They can move quickly to honing and jamming. Among others, especially in non-work related conversations, agreement is much harder to come by – there is so much other stuff in the way!

It is useful to be highly alert if you are asked, or take on the “expert” side of the conversation with most people, and to go meta early on, to be sure the conversation is being shared rather than carried out expressly on your own terms, which can be painful to both parties rather than productive.

And if you are on the receiving end of the wisdom, try and ask direct questions rather than jumping to examples and jamming before invited. The less you presume, the better understood your expert will be and feel, and the sooner either the ball will be handed to you, or the opportunity to jam will emerge between you. Your expert may feel you’re not letting him finish if he has to do more than check in with you periodically on the way to his point, where he believes he will hand you the conversational ball with a flourish.

I say this with chagrin, as I am an improvisation teacher. I don’t have a STEM or computing background, and will speak the first thing that comes to my mind with little or no editing. As a result, I continually violate the conversational safety of passionate experts, by trying to grasp difficult concepts in my own way.

I often wish I had just asked, and/or been bold about leaving the conversation, before letting my imagination get the better of me and derailing the expert with my concept of what is being said, to both of our embarrassment and frustration, even though in social circles, passing the ball back and forth this way is supposed to be the polite norm.

I don’t say expert lightly: I spend a lot of time with, and have a normal amount of respect and envy for people those whose brains easily can go places my brain doesn’t go. I don’t mean to make smarter people than me feel unsafe, or lonely, when I don’t understand or go off on a tangent. I wish I had stronger thinking skills and a bit less impulse. Instead I am, by my smartest friends, seen as a danger to myself because I am so spontaneous.

And that’s sad, because the truth is, I work hard to mind my and my conversation partner’s mutual safety, and in dangerous conversations, the outcome is usually that I make the expert feel safe at my own status’ expense, but my sacrifice is not recognized, and I feel dismissed and condescended to in the end.

Before one painful conversation I can recall, I was healthily curious but completely in the dark when someone told me he was doing work in a specific area of topology, something I know nothing about. I wanted to know more – “Wow – what’s that?” And then his elevator-pitch style answer (he had thought a LOT about what this is) produced in my mind the image of a topographical map, and I asked if it was at all like that, and the answer was, “I don’t do metaphor, no, it’s not like that. It is not ‘like’ anything, it IS this…”

…and I tried, but I simply did not understand a word he said.

Perhaps preserving the integrity of the idea itself matters, or some such thing, if you are going to do work in the field…

…… but I won’t! In the moment, I not only didn’t even have the vocabulary to ask a good question, I felt so reprimanded, I was struck dumb! Clearly, I didn’t have a prayer, at the very least, of being respected for being interested in something so far outside my exposure.

Them, given his violence, and concerned more for the safety of his status than mine, I simply listening a bit, and said thank-you, I can see there is lot to ponder there or some such thing…and both of us quickly went silent and parted feeling we’d wasted our time.

Within seconds, a kinder person who had overheard, told me exactly the way some parts of topology ARE like topography…and far more ways others, or the same parts, are not, but using that silly map in my brain as a springboard.

And though I still don’t know anything about topology, Hey! I heard some new vocabulary, heard some good stories about the second math guy’s path to learning, and we both felt like a success when the conversation was over.

This person was clearly taking care of my status, without condescension (we even laughed a bit) and the deviation from whatever his elevator-pitch for topology is (I’ll never know) didn’t diminish his status at all in my eyes. It raised it.

So there is one more element of safety to be employed, particularly with strangers, or wide circles of friends with divergent interests, or at family reunions – If your conversation partner expresses interest in something you can’t explain in a way they will grasp: if you care about it ending well, it is time to not only jam, but to change your idea of what the conversation is about completely. Be satisfied with less of the substance of your idea being communicated, and work instead toward agreement about what small part of the idea the two of you are able to agree is productive to hone and jam with. And you’ll get through that dinner or lunch or meeting having fun, instead of cursing either his/her or your own ignorance and awkwardness.

Your thoughts?

Malcolm » 29 May 2016 »

Wow! Thanks so much for adding your experiences to the conversation. I think the points that you make about protecting others’ status are good… in some ways this is another lens on the stuff about ensuring safety, and it probably suggests different actions, which is helpful.

There are other times when like, if I don’t trust someone’s thinking enough, and I say “concept X” and they’re like “oh, like Y”, and I think they think they’re honing but Y is totally not the thing, but also if I don’t have enough trust in our relationship to correct them… yeah.

It would be nice to have the meta-safety to be able to talk about this sort of thing more consistently, so that it isn’t one person or the other losing face or losing integrity.

Kenzi » 7 Jun 2016 »

Relevant quote from Gendlin in Focusing Oriented Psychotherapy, on how therapists should navigate corrections/pushback from clients:

“Unlike the gypsy, a therapist does not need the appearance of always being right. Indeed, that appearance should be avoided. It is an unreasonable and unfair demand some therapists put on themselves. I tell my clients constantly, “Of course I don’t know. We won’t know till you find how it is from inside.” Early in therapy, whenever I have said something that turns out to be wrong, I point out my mistake explicitly. I need the client to see that I do not have trouble being wrong, indeed that I expect to be wrong much of the time. Once clients know this, it is easy for them to correct me, and tell me what does come inside them when it is not what I thought. Then my interpretations cannot obstruct the process anymore, and they can help to open things. Does being wrong sometimes erode the therapist’s authority? If I am wrong ten times in a row and right and helpful the eleventh time, then the client gives me credit, and the chain of wrong guesses is forgotten. Indeed the chain of small attempts is hardly noticeable in retrospect, and I still run the risk of seeming magically wise. But if I as therapist “decide” what I can and cannot know, I can get stuck with something I thought should be right, and there cannot be 11 tries. The client then struggles to resist my impulse or tries to make it seem true to save my feelings, or still worse, becomes confused thinking that it must be true. This results in blockage.”

Roughly I think this is the sort of thing that’s a useful clue if you’re working on how to try and improve yourself (it’s good to have others correct you be low-friction), but not something we should generally demand of others, since that’s got a bunch of trickier social issues.

I think what he’s pointing at is quite important when the interaction is anything in the vicinity of one person trying to help solve someone else’s problem. If you’re giving suggestions, or even frameworks or interpretations, you’re going to be wrong a lot no matter how good you are, and you need to remember that and have the error-correction process be as effortless and non-distracting as possible.

Malcolm » 15 Jun 2016 »

Thanks for this! It feels very relevant to some recent thinking of mine too, so I may end up quoting it in a future post.

Have your say!