I have a commitment that I made pretty strongly nearly 7 years ago, and then 3.5 years ago I sort of released it for myself, and even though I don’t particularly think anybody is holding me to it, it feels wise to formally release it. I would say I released it for myself in 2020 the moment I had my non-naive trust dance insight, but since it was a social commitment it feels right to withdraw it from the social sphere too. It’s good, in general, to follow through with commitments; it’s bad to keep pretending to be committed if it’s no longer alive. In this case I would say I realized that the commitment was both self-defeating (as in I could serve its purpose better by dropping it than by keeping it) and in some sense impossible as stated.

In 2021, I published “Mindset choice” is a confusion, which is precisely about this. In it, I describe how while committing to a project can make sense, committing to a way of seeing the world (except as a very bounded temporary experiment) has within it some basic confusion or commitment to not looking and not listening to things that might counter that way of seeing the world. It may be a useful stepping stone, but that doesn’t make it not a confusion.

In 2017, I had a taste of a new experience of easeful flow, that I tried somewhat unsuccessfully to point at in Towards being purpose-driven without fighting myself. The same day I had that experience, I tried to distill my clarity into something that would help me keep it, and wrote up a commitment that I then performed as a small ritual that evening with my learning community as witnesses (I also ritually repeated it daily for months while donning some rings and a necklace, as an attempt to enact it). I still stand by the spirit of the content of the commitment, but the tone of how I approached committing now strikes me as entirely antithetical to everything that was precious about the experience I tasted and loved so deeply.

This blog post is both a formal renouncement of that commitment, as well as a case study in the whole “Mindset choice” is a confusion insight.

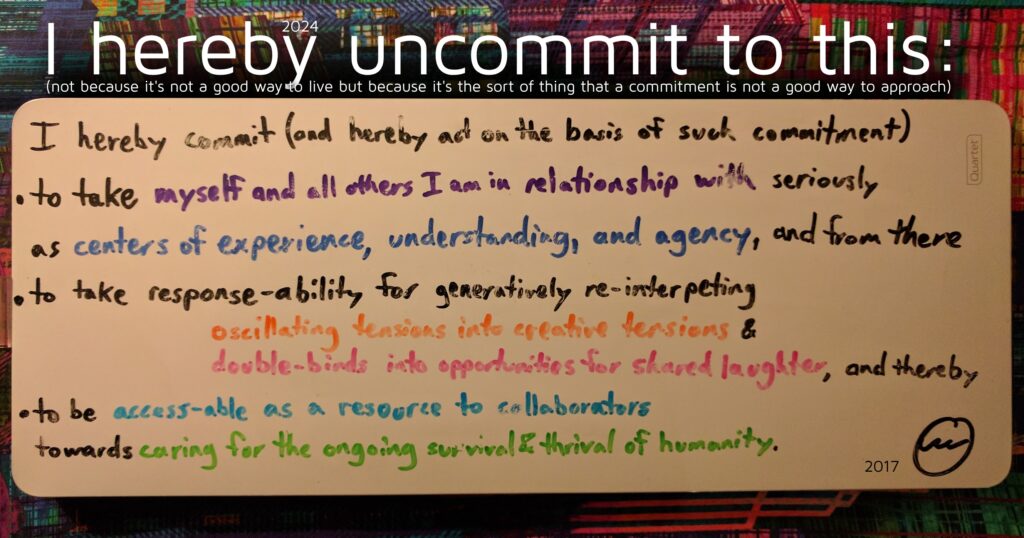

The text of the 2017 commitment read:

I hereby commit (and hereby act on the basis of such commitment)

• to take myself and all others I am in relationship with seriously

as centers of experience, understanding, and agency, and from there

• to take response-ability for generatively re-interpreting

oscillating tensions into creative tensions &

double-binds into opportunities for shared laughter, and thereby

• to be access-able as a resource to collaborators

towards caring for the ongoing survival and thrival of humanity

I hereby uncommit to that, not because it’s not a good way to live, but because it’s the sort of thing that a commitment is not a good way to approach (as far as I can tell). Keep reading for more of my thoughts on this.

The context for how I got here today was that I was re-reading The Guru Papers—one of my all-time favorite books, which interestingly I would have first read in late 2016, relatively shortly before the experience of freedom/liberation in 2017 that plugged into this commitment. Specifically, today I was reading the chapter on addiction, which describes the inner struggle for control between some sense-of-self-that-is-good-in-terms-of-social-uprightness/superegos and some sense-of-self-that-seems-selfish-or-self-centered. The “goodself” and “badself”, although these names are tongue-in-cheek and more refer to what they tend to call themselves; in fact, both have both wholesome desires and self-destructive patterns.

And I was reading about their take on Alcoholics Anonymous…

» read the rest of this entry »By request, a published resource elaborating slightly on my response to a question a friend asked in a groupchat:

A lot of advice is some variation on “express your feelings to not be haunted by them forever,” but what do people mean by ‘express’ here? On one end there is being alone in a room and naming the feeling silently in your head, on the other end is telling your married boss you’re crushing on them, in between is stuff like journaling or going into the woods to scream and writhe or talking it out with a friend.

One model is that the key is to “let yourself fully feel the feeling” and the relevant sense of expression is whatever moves you towards that. Another is that feelings are for taking action in the world so apply appropriate thoughtfulness and discernment to avoid being rash and stupid but ultimately figure out what this trying to make you do and do it, and that will be the relevant expression. Does anybody find this advice helpful and wanna try to convey what it actually means for me?

From my perspective, there’s:

I’m calling these loops because they all have a kind of feedback loop quality to them, even though the feedback is quite subtle. There’s a sense of something landing.

The first loop is about cultivating the sense of “I mean what mean“. Articulating something. Modifying it if it isn’t quite right. Trying again. Saying it out loud and feeling if it resonates. Getting to the point where you’re like “Yeah! THAT!”

Think of a time when you try to explain something to somebody, and they didn’t get it. Whether that was a model or a framework, or some emotional or relational thing or whatever.

» read the rest of this entry »Part 7 of the “I can tell for myself” sequence, picking up where Guru dynamics: “I can show you how to trust yourself” left off:

To the extent that the person in the more student-like role is able to stay in touch with their own direct-knowing even though it conflicts with what they’re hearing from the teacher-role person… now what?

I’ve studied in depth a handful of cases of this (firsthand and secondhand) which is more than most people but not a lot, so I may be missing something major here. These situations can come from the situation described in the previous post, where the student develops self-trust while already inside a container that they had previously been more naïvely surrendered to… or it can involve someone who already has sufficient self-trust to listen to themselves consciously stepping into a learning environment with someone else who also has a lot of self-trust.

In these contexts, where one person is the official or de facto authority in the space, what I’ve seen has tended to involve what-the-authority-knows being the sort of dominant view, with the other person’s knowings (where they contradict, which won’t be everywhere) getting a lot of questioning and suspicion, or treated as irrelevant. This is functionally a form of “oppressive culture”, even if it’s actively intending to be a welcoming culture.

And it turns out that the main approaches are basically the same: stay & pretend, say the unsayable, or leave. But they look a bit different in learning community than in a kind of default societal context.

I did a mix of all three of these when I had my own self-trust breakthrough in 2020, as I wrote about somewhat hotly just after I moved out and more spaciously 2 years later. That’s a great example of a context that was attempting to be welcoming everything but in practice didn’t know how to welcome many things. And there were many aspects of me that could tell they were uniquely welcome there, which is part of what made it all so confusing. And when I tried saying the unsayable there, it was difficult of course, but we were able to sincerely approach the challenge together to some degree. There was no “you can’t say this”, just a “you can only say this if it also accounts for this other thing that’s really important” which was around the edge of my ability.

» read the rest of this entry »Fourth in a sequence:

In the first piece, I distinguish between two kinds of knowing, one that I call “I can tell for myself” and the other that I call “taking someone’s word for it”. These are my approach to speaking in plain language about what’s sometimes called gnosis (as contrasted with perhaps “received knowing”).

In the second, I explore the many pressures from childhood, teenagerhood, and spiritual communities, that lead to people taking someone’s word for it even when it contradicts what they can tell for themselves, and how that leads to habitual ignoring of being able to tell for oneself. In the third, I explore the systemic double-binds of culture that shear peoples’ knowing from their honesty.

This post, the primacy of knowing-for-oneself, is more technical: to investigate the relationship between these different kinds of knowing, and make it clear how while words can be used to guide people into being able to tell for themselves, telling for oneself goes back further in evolutionary history, and that without it we wouldn’t even be able to take someone’s word for it.

If that already feels obvious to you, feel free to skip ahead to the next post: Reality distortion: “I can tell, but you can’t”

This section is a response to this comment by a draft reader (who was not my wife when she wrote this comment but is now) on the earlier posts:

My theory: taking other people’s word for it is the default way of knowing things (that we have to rely on when we’re children) and developing the capacity to know for ourselves (and to know when to trust our own knowing) takes more development.

Insofar as it might seem like “taking someone’s word for it” is the default, my guess is that it’s because the phrase “I can tell for myself” is already contrasting itself with something else. And it is the case that we aren’t born knowing how to deal with conflicts between what we can tell for ourselves and what others tell us. That’s something we have to learn, whether by cultivating it the whole time or by having a sudden waking-up experience as an adult where we realize we’ve been ignoring ourselves.

It seems overwhelmingly obvious to me that knowing for ourselves is the functional default way of knowing, and prior to taking others’ word for it in all ways: evolutionarily, developmentally, and experientially/ontologically. (However, in the same way that someone can have an unnatural and unhealthy habit that is nonetheless a default in some sense, people can develop a “default” way of knowing that involves taking others’ words for it).

First, about words. Since this is an essay, everything I’m saying is expressed in words. However, the knowing is not in the words. “I can tell for myself” knowings can be referred to by a proposition (eg “I can ride a bike”, “it is raining outside”, “my mom loves me”) but they are grounded in the other kinds of knowing: procedural, perspectival & participatory, to use Vervaeke’s model. And the ability to be able to tell if a given proposition is true/relevant is part of the sense of “I can tell for myself”, and is not itself made out of propositions, even in domains of logic or mathematics.

Second, about defaults. Consider animals. They can tell for themselves nearly everything they need to know. They periodically do some interpretation, perhaps of a mating call or a warning call, but it seems to me that this is still better understood not as “taking someone’s word for it” but simply “acting on the basis of what is implied by the sound”. They’re not forming generalizations or having “beliefs” about things elsewhere and elsewhen, on the basis of these sounds. But when the animals are direct-knowing, they aren’t thinking “I can tell for myself”, they’re simply knowing. They don’t have a “taking someone’s word for it” to contrast this more basic kind of knowing with.

Baby humans start to discern for themselves that they can move their limbs and see stuff, and that they’re hungry, well before they can understand language and be told anything true or false. They can tell for themselves that faces are important—and that some particular faces are extra important. They can tell for themselves that boobs are great. They can tell for themselves that having a dirty diaper sucks. And they can tell for themselves a lot of subtle stuff about the attention and vibe of the people around them—more than most give them credit for.

Third, about meaning. The only way we can take someone’s word for it is on the basis of what they appear to us to mean, which is a kind of knowing that is much more like the “I can tell for myself”. It’s just that we often take this part for granted. We usually don’t realize the active interpretive role that we are playing in being able to know anything on the basis of someone else making mouth sounds.

Having said all of this, yes, as humans we do need to rely a lot on taking other people’s word for it. Humans live in cultures, and there is no default human behavior absent a culture, nor a default culture for humans to live in. And in particular, our sense of social expectations comes in large part from the words of others, whether that’s an adult enculturating a kid or an employer enculturating a new hire. Sometimes this is benign. What I want to highlight is that every time we take other people’s word for something in a way that (seemingly) contradicts what we can tell for ourselves, we introduce a confusion into not just what we know but into the very means by which we go about knowing things and trusting ourselves.

It seems to me that even though we do need to tell kids a bunch of stuff and have them use those knowings even though they can’t yet tell for themselves, we could also do so in a way that 100% respects their experiential frames—not trying to force an override. We can point things out to people (kids or otherwise) and we can guide them into having experiences that will allow them to tell for themselves, and this is different from trying to force them to see something a particular way. (This is adjacent to how in coercion in terms of scarcity and perceptual control I talk of coercion as trying to force a certain behavior.) We can do this by acknowledging uncertainty, different perspectives, and where we missed things… and by supporting kids to back their own knowings when they differ from ours, even if we say “and right now I have to make the decision as the parent/teacher/etc, and this is the call I’m making”. However, attempting to form such a pocket of sanity in a larger culture that’s oppressive can have additional challenges. Somehow a kid would still need to learn in which contexts they can safely be honest about what they’re seeing.

As I said at the top, insofar as it might seem like “taking someone’s word for it” is the default, my guess is that it’s because the phrase “I can tell for myself” is already contrasting itself with something else. To some extent I chose it for that purpose, because a lot of the adult quest of developing and refining one’s knowing involves rejecting a bunch of stuff someone else told us when we were more impressionable but which we can now tell doesn’t hold up. Because while animals and newborns can tell for themselves, newborns have no idea how to integrate what they can know directly with what others tell them. This must be learned. How do I generalize what I can tell for myself, while acknowledging that it also seems to contradict what you’re telling me?

In any case, our societies currently mostly teach the opposite of that, in the way that they go about teaching us the cultural knowledge we’re supposed to have. And it’s important to convey this knowledge to people—that’s utterly central to what it means to be human. But at this point in history, it’s possible to convey most of the key cultural knowledge while also conveying how to sanely relate it to your own knowing. It’s not about the overt messages but about the relationship we’re trained to adopt between what we’re told and what we can tell for ourselves.

There are some pitfalls, however, when trying to create learning environments for people to develop this new capacity…

Next post in sequence: Reality distortion: “I can tell, but you can’t”

Another “explain what you’re on about right now, in one breath, standing on one foot“. See the NNTD one here.

“Partswork” (usually “parts work” but it’s on its way to being one word like “cupboard”) is sort of a catch-all term for therapeutic or introspection approaches that involve orienting to yourself as having different parts, that have different desires, wants, needs, beliefs, experiences, perspectives, etc.

Speaking in terms of “part of me” is very common. I would be surprised to find a reader of this post who has never used a phrase like “part of me wants to go out tonight, but part of me wants to stay in” or “part of me distrusts him” or “part of me really just wants to finish this right now” or “part of me wants to do nothing but eat chocolate all day” or “part of me thinks nobody will ever love me”.

And this was the origin of Internal Family Systems therapy, the most famous form of partswork. When Dick Schwartz was working with his clients, he noticed them saying phrases like that, and started developing a theory of these “parts”. The term “parts” came from the common language of his clients. He then developed a powerful taxonomy of different types of parts (exiles & protectors (subtypes: managers & firefighters)) which relate in particular ways and have specific types of relationships with each other. In IFS sessions, it’s common for the parts to be given names (perhaps by asking the part what to call it) and to have fairly stable identities across different sessions over weeks or months.

People have different models of what’s going on there, and whether these parts truly “exist” or whether they’re just a useful interface or metaphor for relating with oneself. I don’t have a particular take on that—in fact, I’m not even entirely certain that those two views refer to a different world (Don Hoffman posits that all perception is interface). The parts obviously aren’t discrete in the way car parts are; they’re much more organic and intertwingled.

What I do have a take on is that you don’t need to reify or name parts in order to do partswork. You can—for big issues this can be really helpful. The IFS model is good and seems to track for a lot of people.

But it can also add unnecessary overhead, and make it hard to notice that the same principles of internal conflict apply on other scales as well.

This is particularly salient to me since my introduction to the importance of inner conflict wasn’t IFS, it was Perceptual Control Theory, whose parts are very tiny and in some ways ephemeral.

» read the rest of this entry »The following is a piece I wrote a year ago. A few months back I started editing it for publication and it started evolving and inverting and changing so dramatically that I found myself just wanting to publish the original as a snapshot of where my thinking was at about a year ago when I first drafted this. I realized today that attempts to write canonical pieces are daunting because there’s a feeling of having to answer all questions for all time, and that instead I want to just focus on sharing multiple perspectives on things, which can be remixed and refined later and more in public. So, with some minor edits but no deep rethinking, here’s one take on what coercion is. And you might see more pieces here soon that I let go of trying to perfect first.

Coercion = “the exploitation of the scarcity of another, to force the other to behave in a way that you want”

The word “behave” is very important in the above definition. Shooting someone and taking their wallet isn’t coercion, as bad as it is. Neither is picking their pocket when they’re not paying attention. But threatening someone at gunpoint and telling them to hand over their wallet (or stand still while you take it) is coercion. This matches commonly accepted understandings of the word, as far as I know.

A major inspiration for this piece is Perceptual Control Theory, a cybernetic model of cognition and action, which talks about behavior as the control of perception. I’m also mostly going to talk about interpersonal coercion here—self-coercion is similar but subtler.

If someone has a scarcity of food, you can coerce them by feeding them conditional on them doing what you want. This is usually called slavery. One important thing to note is that it requires you physically prevent them from feeding themselves any other way! Which in practice usually also involves the threat of violence if they attempt to flee and find a better arrangement.

In general, a strategy built on the use of coercion means preferring that the coerced agent continue to be generally in a state of scarcity, because otherwise you would be unable to continue to control them! (Because they could just get their need met some other way and therefore wouldn’t have to do what you say!)

» read the rest of this entry »Letting other people make their own mistakes is a very basic and underappreciated form of respect.

The main cause of failing to do this afaict is having an overzealous self-other boundary that includes the other person and then says “I would never make a mistake like that!” and then tries to correct their behavior with our own principle bruh, they’re not you!

Letting people have their actual understandings (even when they’re misunderstanding you)

Letting people try an approach (even if you know/think it won’t work)

Letting people have their triggers & neuroses (even if they make no sense to you)

= all forms of acceptance & respect

» read the rest of this entry »I am coming to the conclusion that everything I was trying to get myself to do is better approached by exploring how to allow myself to do it.

😤✋❌ how do I get myself to do the thing?

😎👉✅ how do I allow myself to do the thing?

It’s obvious, on reflection: if “I want to do the thing”, great! The motivation is there, for some part of me that has grabbed the mic and is calling itself “Malcolm”.

The issue is that some other part of me doesn’t want to do the thing, for whatever reason, or I’d simply be doing it. (To be clear, I’m not talking about skills, just about actions, that I’m physically or mentally capable of taking.)

So there’s a part of me, in other words, that isn’t allowing me to do the thing that I supposedly want to do (I say “supposedly” because the part claiming I want to is necessarily also partial).

…and that’s the part with the agency to enable the thing!

So the question is:

» read the rest of this entry »I scheduled this post to go live as a showtime, then realized I wasn’t sure if “consciousness” is the right way to even frame this, but I let it go live anyway. In some sense it could be called “sanity”, but that has its own challenging connotations. I use both terms sort of synonymously below; I might decide later that yet a third word is better. There’s also a lot more that I can—and will—say about this!

I figure collective consciousness can be summarized as the capacity for a group of people to:

(Jordan Hall’s 3 facets of sovereignty: perception, sensemaking and agency.)

I like to say “Utopia is when everyone just does what they feel like doing, and the situation is such that that everyone doing what they feel like doing results in everyone’s needs getting met.” On a smaller group, a sane We is when everyone in the We does what they feel like in the context of the We, and they are sufficiently coherently attuned to each other and the whole such that each member’s needs/careabouts get met.

In some sense, obviously, if there existed an X such that if you supported the X it would cause everything you want to be achieved better than you could manage on your own, you’d want to support the X. Obviously, from the X’s perspective, it would want to support the individuals’ wants/needs/etc to get met so that they have more capacity to continue supporting it supporting them supporting it [ad infinitum]. This is the upward spiral, and it’s made out of attending to how to create win-wins on whatever scale.

As far as I can tell, there can’t exist such an X that is fully outside the individual(s) it is supporting. In order for it to actually satisfy what you actually care about, consistently and ongoingly, it needs a direct feedback loop into what you care about, which may not be what you can specify in advance. Thus you need to be part of it. The system gives you what you need/want, not what you think you need/want, in the same way that you do this for yourself when you’re on top of things. Like if you eat something and it doesn’t satisfy you, you get something else, because you can tell. (This is related to goodhart and to the AI alignment puzzle).

Fortunately, as far as I can tell, we can learn to form We systems that are capable of meeting this challenge. They are composed of ourselves as individuals, paying attention to ourselves, each other and the whole in particular ways. Such a We can exist in an ongoing long-term explicit committed way (eg a marriage) or one-off task-based unremarkable ad hoc way (eg a group gathers to get someone’s car unstuck, then disappears). Or it could be a planned and explicit temporarily-committed group (eg a road trip) or an emergent spontaneous group (eg some people who meet at burning man and end up being adventure buddies for the rest of the day, taking care of what arises).