Some years ago, I invented a new system for doing stuff, called Complice. I used to call it a “productivity app” before I realized that Complice is coming from a new paradigm that goes beyond “productivity”. Complice is about intentionality.

Complice is a new approach to goal achievement, in the form of both a philosophy and a software system. Its aim is to create consistent, coherent, processes, for people to realize their goals, in two senses:

Virtually all to-do list software on the internet, whether it knows it or not, is based on the workflow and philosophy called GTD (David Allen’s “Getting Things Done”). Complice is different. It wasn’t created as a critique of GTD, but it’s easiest to describe it by contrasting it with this implicit default so many people are used to.

First, a one-sentence primer on the basic workflow in Complice:

There’s a lot more to it, but this is the basic structure. Perhaps less obvious is what’s not part of the workflow. We’ll talk about some of that below, but that’s still all on the level of behavior though—the focus of this post is the paradigmatic differences of Complice, compared to GTD-based systems. These are:

Keep reading and we’ll explore each of them…

» read the rest of this entry »We interrupt your regularly scheduled metaprogramming to bring you a stream-of-consciousness musing on the nature of being, and related topics. This is more me playing with ideas than trying to make any case in particular.

Sometimes I forget that I exist in the physical realm. That I’m made of stuff. Less so, perhaps, than many of my mathier friends, but still fairly often.

In one sense, this is true: what “I” am is an identity, a sense of self, a pattern. The pattern happens to currently be expressed in a very physical sense: my computations may be virtual in a sense, but they’re tightly coupled to input from the physical world, including parts of the physical world that are also considered to be “me”. The parts of my body.

But of course they’re “me” for convenience, because they’re an extension of my cognition. Immediately after my finger is cut off, it’s very immediately no longer “me”. I wonder if people who are paraplegic don’t feel like their legs are “them”. Does someone with phantom limb syndrome include their phantom limb in their notion of “me”, even if it doesn’t exist in the normal sense?

Relatedly, we often feel like the rogue agents in our brains aren’t us. Hell, sometimes I’ve even said/heard “my brain just generated a thought, which was…” So I guess a large fraction of my cognition also isn’t exactly “me”. Dis-identification from my thoughts, for better or for worse.

Seriously though, we’re made out of stuff. » read the rest of this entry »

In January, while doing an internship in San Francisco, I found myself in the hospital. Fortunately, I needed to have insurance to even step foot in the states, so the hospital stay passed without a hitch. After my first night there, someone came by from the company I was working for and brought me food. However, the hospital was already feeding me, and they’d brought me, among other things, a whole fruit basket! I can’t eat so many apples and oranges by myself even when healthy.

I therefore decided, when I was discharged, that instead of just throwing out the remaining food, I would try to give it to the people on the street near Union Square who were begging. What followed was a remarkable experience.

The first observation I made was that the street people weren’t nearly as omnipresent as I’d thought—I lived near Union Square and I had the sense that I’d be able to give away the food in about 15 minutes easily. The first bit, indeed, went quickly, but then I had to spread out.

More significantly, I found it to be a profoundly unique feeling to be looking for beggars. So often the impulse is to try to avoid eye contact or to look away, in an attempt at denial or at least an attempt to avoid feeling obliged to help. This was a 180° shift for me, and was quite a surprise.

A similar experience showed up for me this week, when I was at a friend’s house and he had a device that looked like a squash racket with metal strings, that would literally zap fruit flies out of the air. I grabbed it and obliterated a few, and then found myself looking for fruit flies… opening cupboard doors in hopes of finding some. What?! If you’d told me last week that I’d spend some of this week excitedly looking for fruit flies (and disappointed not to find any) I would have been quite skeptical.

But it was fun! And so was interacting with the people on the street, once I was feeling truly and deeply generous. I also learned that many homeless people will refuse apples—because they don’t have sufficient teeth with which to eat them. That was totally something I took for granted.

I think there’s a broader lesson here, which is that a tiny shift in intention can transform situations from being unpleasant or tiring into being exciting and enjoyable. This can be applied to one’s life (making a game out of a chore) or could be used to create a product like that bug zapper. Any product that takes a necessary part of life and makes it fun instead of unpleasant offers a clear value to the users.

The Living Room Context holds that the subjective is all we have. This is true in the sense that we only have our own perceptions of things and our own models. However, barring solipsism, it appears to be valuable to talk about things as having a sense of objectivity.

I had long thought of objectivity as “reality” or “the way things are”. This sort of definition makes sense with the phrase “objective truth”. In learning about subjective truth—the known truth of our own experience—I’ve come to understand that while it can make sense to model the existence of some kind of external reality, everything we know about that objective reality is itself… a subjective model, contained in each of us, the subjects.

I tried to understand the objective by simply modelling it as inhuman, except no, nonhumans experience subjective perception as well, though they may not have thoughts about it. Or what about aliens? This works on the level of “if a tree falls in a forest, it makes air vibrations but sound only happens when a creature with ears experiences those vibrations”.

Then I thought about it from a scientific perspective: objective truth, I thought, is when you’re saying some model is presently as close as possible (given available data and modes of thinking) to the model you would anticipate having given infinite investigation. At the very least, even if not as close as possible, you’re asserting that it’s better than the prevailing model. Importantly, that it’s better than the prevailing model for everyone, not just you.

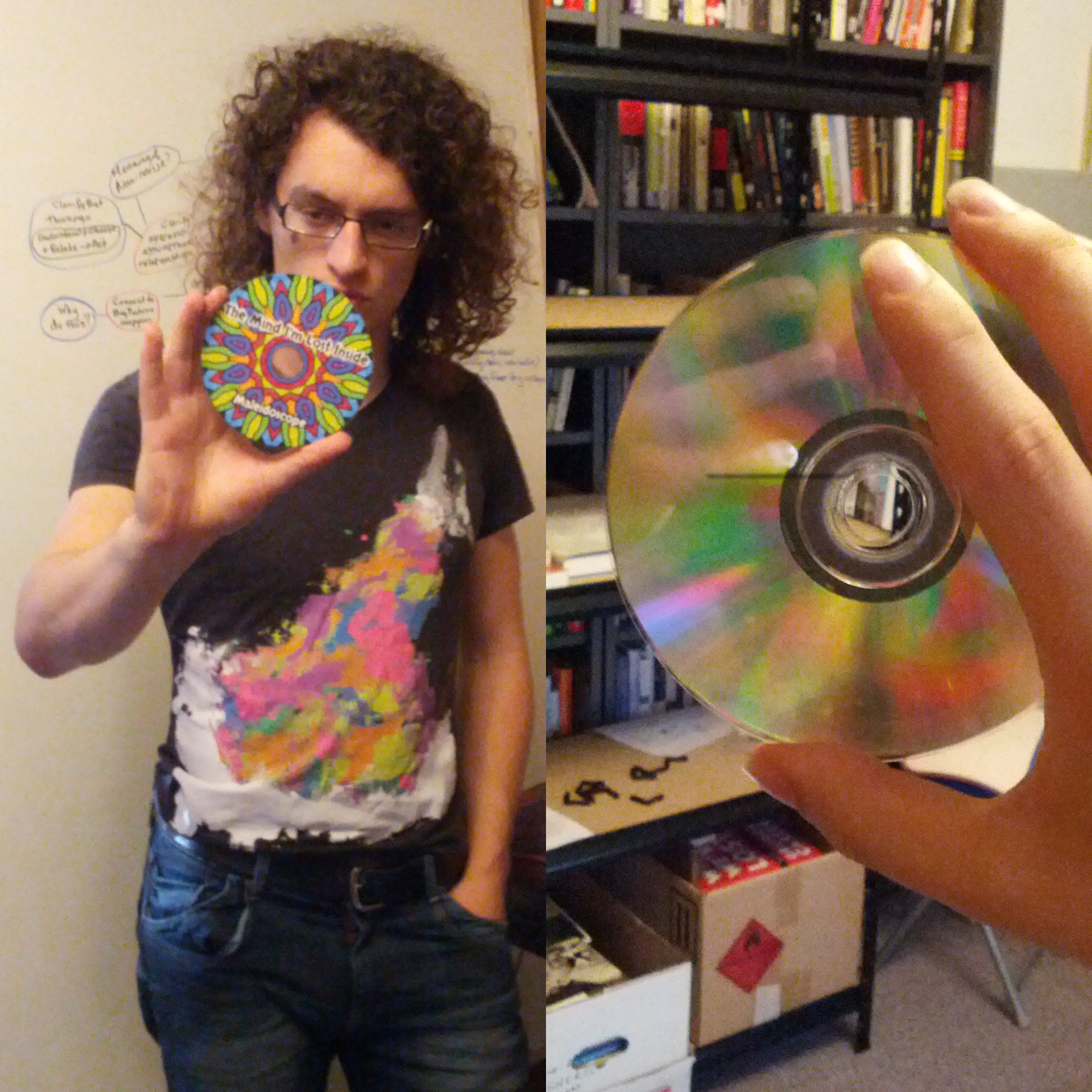

Your perspective and mine. Visually, at least. I also have a strong emotional experience, since that CD is my first album.

So maybe the objective is describing something independent of perspective? As in, devoid of subjectivity? Sort of, but that’s not quite it either. If I hold up a CD, facing you, then your subjective description is the cover art, and mine is just a shiny disc, but what is the objective description? In what sense can such a description exist?

I propose that the objective can be best modelled not as being independent of perspective but rather dependent on it. Like a function. The objective description is a way of answering the question, “if I perform some known kind of measurement on this object/phenomenon, what do I expect the result to be, given the perspective from which I perform the measurement?” Note that there remains the subjective component of there being a certain subject who holds the expectation that the results of said measurements would be well-mapped by said function.

I think that a common source of conflict is when we attempt to make objective descriptions without accounting for certain dimensions by which the subjective perspectives can vary. It’s easy to ask “what photons would enter my eyes if I were standing in a different location?” but much harder to ask “how would I perceive this interaction if I had been born and raised a in X circumstances?” where X could be a different period of history, or a different country, or even a different social class. This is what makes objective descriptions dangerous—we usually don’t know how to define the function across the full breadth of human perspectives, and so what we say is likely to be misinterpreted.

From the LRC list of commitments and assumptions:

I commit to speaking only out of and about my own personal experience and understanding. When I speak of others experience or ideas, it is my experience of them I speak of.