Hello to David Sauvage (cc Daniel Thorson)

I’ve just listened to your podcast interview and want to expose myself to you as someone deeply tracking the field as well.

I’m writing this letter to you from a plane flying west in a gorgeous multi-hour sunset, from Ontario to Vancouver. I’ve just wrapped up a weeklong adventure that I described in this other open letter as a meta-protocol jam, where I was interfacing with some of the people I know who are most plugged in with the leading edge of collective decision-making.

I felt huge resonance with almost everything in the podcast, even though I know very little about Occupy.

Lots of possible starting points here. Let’s use this:

The right goal is not consensus but resonance. A collective experience of the truth.

When consensus-driven decision-making works, it’s because it does this.

Absolutely. How this occurs to me is that the key difference is: consensus is allowed to be hard-blocked by dissociated narrowly-fixated left hemisphere stuff, whereas a resonance-oriented approach refuses to stop there. Though those views still need to be integrated! And there’s a huge puzzle on how to do that without losing your own view, which I’ve been investigating with my Non Naive Trust Dance framework! And I’m seeing how the moves I’ve been encouraging people to make as part of that, of naming “I can’t trust X” or “I can’t rest at ease with X”, partially helps people actually get more subjective & embodied, and to open to uncertainty.

A lot to unpack there. My NNTD framework is something I’ve developed for orienting to the creation of intersubjective truth, starting from subjective truth. One lens I have on trust is “trust is what truth feels like from the inside”. Simultaneously, trusting something means being able to be at ease in relation to it. Sometimes we generate this ease in a naive way, by suppressing our concerns, but this is unstable—when those concerns re-arise, they then disrupt apparent group consensus or even apparent resonance that was existing in denial of the concerns. As I’m articulating that right now, in relation to what I just listened to, I’m feeling the inherent relationship between truth and values—what is deeply right for us (our subjective values) aren’t arbitrary.

It seems to me that we don’t choose them so much as discover them. We discover the tradeoffs we truly want to make, and then it doesn’t even feel like a sacrifice. So the decision-making process that you outlined is one of mutual/collective discovery of what we in fact deeply want once all perspectives are heard.

» read the rest of this entry »I wrote this addressed to a learning community of a few dozen people, based in Ontario, that evolved from the scene I used to be part of there before I left in late 2020. I’m about to visit for the first time in nearly 2 years, and I wanted to articulate how I’m understanding the purpose & nature of my visit. It’s also aimed to be a more general articulation of the kind of work I’m aiming to do over the coming years.

This writing is probably the densest, most complete distillation of my understandings that I’ve produced—so far! Each paragraph could easily be its own blog post, and some already are. My editing process also pruned 1700 words worth of tangents that were juicy but non-central to the point I’m seeking to make here, and there are many other tangents I didn’t even start down this week while writing this. Every answer births many new questions. See also How we get there, which begins with the same few paragraphs, then diverges into being a manual for doing this process.

To “jam” is to improvise without extensive preparation or predefined arrangements.

“Convening” means coming together, and Ontario is of course that region near the Great Lakes.

As for the “meta-protocol”…

It seems to me that: consistent domain-general group flow is possible and achievable in our lifetimes. Such flow is ecstatic and also brilliant & wise. Getting to domain-general group flow momentarily is surprisingly straightforward given the right context-setting, but it seems to me that it usually involves a bit of compartmentalization and is thus unsustainable. It can be a beautiful and inspiring taste though. (By “domain-general” I mean group flow that isn’t just oriented towards a single goal (such as what a sports team has) but rather an experience of flow amongst the group members no matter what aspects of their lives or the world they turn their attention to.)

It seems to me that: profound non-naive trust is required for consistent domain-general group flow. This is partially self-trust and partially interpersonal trust.

It seems to me that: in order to achieve profound non-naive trust, people need to reconcile all relevant experiences of betrayal or interpersonal fuckery they’ve had in their life. This is a kind of relational due diligence, and it’s not optional. It’s literally the thing that non-naive trust is made out of. That is, in order for a group to trust each other deeply, they need to know that the members of that group aren’t going to betray each other in ways they’ve seen people betray each other before (or been betrayed before). Much of this is just on the level of trusting that we can interact with people without losing touch with what we know. So we either need to find a way to trust that the person in front of us won’t do something that has disturbed us before, or that we ourselves aren’t vulnerable to it like we were before, which involves building self-trust. It takes more than just time & experience to build trust—people need to feel on an embodied level why things go the way they’ve gone, and see a viable way for them to go differently.

It seems to me that: people attempt to do this naturally, whenever they’re relating, but understanding what’s going on and how to make it go smoothly can dramatically increase the chances of building trust rather than recapitulating dysfunctional dynamics by trying to escape them.

» read the rest of this entry »Last year I started a new habit of taking a weekly “day off”. The two key things that make my day a “day off” are:

I’ve kind of tried to keep those 2 elements alive during the day too though, meaning:

If some event is particularly juicy and only happens that day, I might put it on my 2nd calendar (more of an “fyi”) so that I know that the opportunity is there.

But I make it clear for people not to assume I’ll go.

Sometimes, a day or two before my day off, I imagine what I might do that day, but I still have to find out.

Saturday-me can delight in the present FEELING of how satisfying it might feel to spend my Sunday day off finishing an old backburner project… but it’s a fantasy, not a plan!

If anyone asks me “what are you doing on tomorrow/Sunday?” I just say “whatever I feel like doing!”

It’s simultaneously kinda scary & profoundly liberating to tell people I’m not available on a given day not because I’m busy but because my schedule is completely empty and NOBODY (not even me) is allowed to fill it.

» read the rest of this entry »I am coming to the conclusion that everything I was trying to get myself to do is better approached by exploring how to allow myself to do it.

😤✋❌ how do I get myself to do the thing?

😎👉✅ how do I allow myself to do the thing?

It’s obvious, on reflection: if “I want to do the thing”, great! The motivation is there, for some part of me that has grabbed the mic and is calling itself “Malcolm”.

The issue is that some other part of me doesn’t want to do the thing, for whatever reason, or I’d simply be doing it. (To be clear, I’m not talking about skills, just about actions, that I’m physically or mentally capable of taking.)

So there’s a part of me, in other words, that isn’t allowing me to do the thing that I supposedly want to do (I say “supposedly” because the part claiming I want to is necessarily also partial).

…and that’s the part with the agency to enable the thing!

So the question is:

» read the rest of this entry »In which I answer 6 questions from a friend about my Non-Naive Trust Dance framework. I’ve said a lot of this before, but kind of all over the place, so here it is collected together, as yet another starting point.

The questions:

My experience of writing this post has caused me to have a sort of meta-level answer to a question I see behind all of these questions, which is “why is the NNTD so important? should I care?” And my answer is that I don’t actually think NNTD is that significant on its own, and that most people should care if it intrigues them and seems useful and not otherwise. What makes the NNTD important is that it’s a new & necessary puzzle piece for doing world-class trust-building, which is necessary for making progress on collective consciousness, and that is important. But if you’re not working on that, and NNTD doesn’t interest you, then maybe you want to put your attention elsewhere!

It is, perhaps unfortunately, all 3 of those things. I would say that in some sense it’s mostly a worldview or a theory, and any practice that emerges out of that could ultimately be described as simply being what it is. Certain practices make more or less sense in light of the theory, but it’s descriptive rather than prescriptive.

So as a worldview, the NNTD view sees all beings as constantly engaged in trust-dancing. “Trust” and “truth” have the same root, and trust can be thought of as essentially subjective truth, so trust-dancing with reality is figuring out what seems true from your vantage point. Where naivety comes in is that humans have a tendency to try to interfere with each others’ sense of what’s true, resulting in apparent trust that’s actually layered on top of repressed distrust.

» read the rest of this entry »I scheduled this post to go live as a showtime, then realized I wasn’t sure if “consciousness” is the right way to even frame this, but I let it go live anyway. In some sense it could be called “sanity”, but that has its own challenging connotations. I use both terms sort of synonymously below; I might decide later that yet a third word is better. There’s also a lot more that I can—and will—say about this!

I figure collective consciousness can be summarized as the capacity for a group of people to:

(Jordan Hall’s 3 facets of sovereignty: perception, sensemaking and agency.)

I like to say “Utopia is when everyone just does what they feel like doing, and the situation is such that that everyone doing what they feel like doing results in everyone’s needs getting met.” On a smaller group, a sane We is when everyone in the We does what they feel like in the context of the We, and they are sufficiently coherently attuned to each other and the whole such that each member’s needs/careabouts get met.

In some sense, obviously, if there existed an X such that if you supported the X it would cause everything you want to be achieved better than you could manage on your own, you’d want to support the X. Obviously, from the X’s perspective, it would want to support the individuals’ wants/needs/etc to get met so that they have more capacity to continue supporting it supporting them supporting it [ad infinitum]. This is the upward spiral, and it’s made out of attending to how to create win-wins on whatever scale.

As far as I can tell, there can’t exist such an X that is fully outside the individual(s) it is supporting. In order for it to actually satisfy what you actually care about, consistently and ongoingly, it needs a direct feedback loop into what you care about, which may not be what you can specify in advance. Thus you need to be part of it. The system gives you what you need/want, not what you think you need/want, in the same way that you do this for yourself when you’re on top of things. Like if you eat something and it doesn’t satisfy you, you get something else, because you can tell. (This is related to goodhart and to the AI alignment puzzle).

Fortunately, as far as I can tell, we can learn to form We systems that are capable of meeting this challenge. They are composed of ourselves as individuals, paying attention to ourselves, each other and the whole in particular ways. Such a We can exist in an ongoing long-term explicit committed way (eg a marriage) or one-off task-based unremarkable ad hoc way (eg a group gathers to get someone’s car unstuck, then disappears). Or it could be a planned and explicit temporarily-committed group (eg a road trip) or an emergent spontaneous group (eg some people who meet at burning man and end up being adventure buddies for the rest of the day, taking care of what arises).

In addition to writing blog posts, now and then I write songs. Here’s my latest. It’s a deep reflection on the most challenging decision I’ve ever made in my life—to end the 5 year relationship I’ve had with Sarah. There’s a lot I could write about that, and I’m sure I will, but for now I mostly want to let the song speak for itself, and then reflect on why I wrote it and why I’m sharing it.

While queuing up the 100× vision post last week, I realized I hadn’t published another vision doc that I wrote awhile back and had been sharing with people, so I figured out would be good to get that out too. In contrast to the 100× vision, which is imagining the 2030s, this one is the adjacent-possible version of the vision—the one where if you squint at the current reality from the right angle, it’s already happening. I wrote this one originally in November 2020. There’s also A Collaborative Self-Energizing Meta-Team Vision, which is a looser sketch.

This is intended to evoke one possibility, not to fully capture what seems possible or likely.

In fact, it is highly likely that what happens will be different from what’s below.

Relatedly, and also central to this whole thing: if you notice while reading this that you feel attracted towards parts of it and averse to other elements (even if you can’t name quite what) then awesome!

Welcome that.

Integrating everyone’s aversion or dislike or distrust or whatever is vital to steering towards the actual, non-goodharted vision. And of course your aversion might be such that it doesn’t make sense for you to participate in this (or not at this phase, or not my version of it). My aim is full fractal buy-in, without compromise.

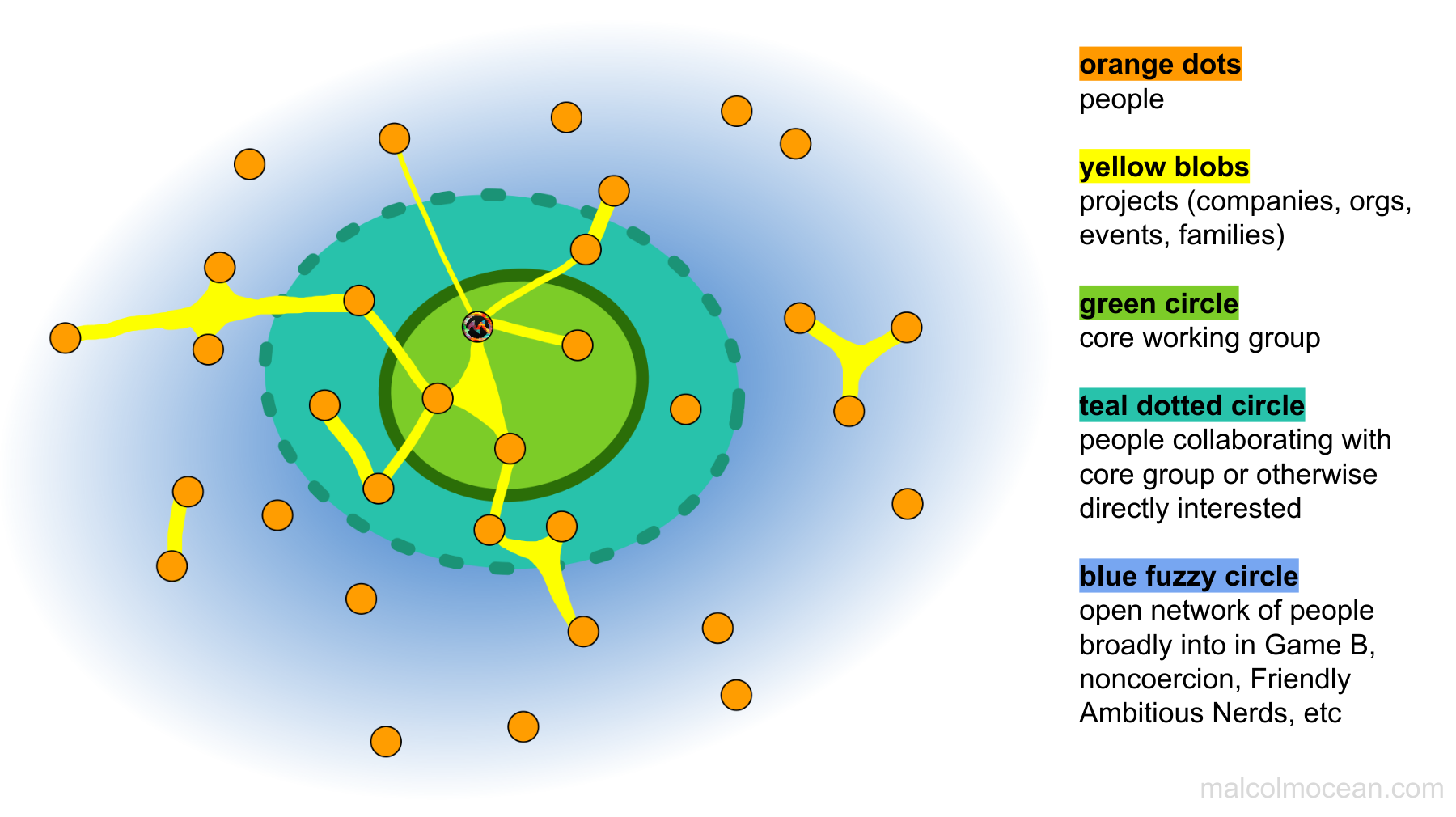

This diagram (except for the part where one of the people is marked as me 😉) could apply to any network of people working on projects together, that exists around a closed membrane, but I want to elaborate a bit more specifically about what I have in mind.

The Collaborative self-energizing meta-team vision public articulation 2020-10-19 is describing the outermost regions of the above diagram, without any reference to the existence of the membranes. The open-network-ness is captured by this tweet:

This is a beacon—want to work with people doing whatever most deeply energizes you? Join us!…how? There’s no formal thing.

Joining = participating in this attitude.

The attitude is one of collaboration in the sense of working together, and in particular working together in ways that everybody involved is excited about and finds energizing and life-giving. Where people are motivated both by the work they’re doing as part of the collaboration, and by the overall vision. That’s not to say it’ll all be easy or pleasant or straightforward—working with people is challenging! And that’s where the other layers come in.

I’m now going to jump to the innermost, closed membrane, because the dotted-line teal group kind of exists as a natural liminal area between that and the wider group.

» read the rest of this entry »

Last year, I was inspired by a fellow friend and consciousness-evolution-furtherer, who sent a screenshot of his “100× vision” in a newsletter. I replied “I feel dared by you doing that to do something similar myself.” A couple months later, I finally wrote something up. At the time it felt too big and scary to post anywhere, but perhaps I’ve grown, or just gotten more comfortable with it, or shared it with enough people who responded positively… because I now feel pretty easeful about posting it to my blog.

I’ve written some adjacent-possible visions. This one is about 10-15 years into the future—sometime in the 2030s—and is written as if I wrote it then, in the present tense, describing what I see when I look around at my life. It’s not a complete description of what I want—it’s actually very abstract and is designed to be a sort of generic placeholder vision that many people would also find themselves wanting. A friend recently challenged me to make an actual personal vision, so I’ve now done that too and it’s called “Malcolm’s bespoke personal selfish vision” but that I’m also not ready to publish. Wants can be very vulnerable!

Without further ado: here’s what I see from an imagined place in the 2030s:

I’m deeply embedded in beautiful, bountiful, brilliant collaborative human superintelligence on many scales, of which I’ll highlight 3 below. I’m not the leader on any of these scales – to some extent because there is no single leader but also because inasmuch as there is, that’s not what I’m called to do. But I was one of the major figures getting it all off the ground years ago, because I knew I needed all of this to exist in order to be thriving this much… I wouldn’t settle for anything less, and nobody else was already simply doing it in a way I could join, so I Sourced some of it.

Since precisely *what* we’re all working on at this point is highly contingent and path-dependent on both what else has happened and is happening in the world, as well as on who’s involved, and I’m writing this from a trans-timeline perspective that’s independent of those details, I can’t specify in detail what projects we’re working on, but I can describe the rough structure of things as they look right now in 2035.

I’m part of a slowly growing group of 10-20 people who are capable of getting profoundly in sync and are thus able to actually think as well as… it’s hard to put it but something like “as well as a single human could if it had 10-20x as many neurons”. Another analogy might be “a five year old is to an adult as an adult is to this collective brain”. We’re able to solve problems better than almost any individual could (except given specific expertise). Individual wisdom is integrated—the group is wise about anything that any individual in the group is wise about.

This group is one of several that are connected, and we’ve had some splittings and mergings over the years to find better configurations of people.

We have been and are ongoingly achieving this through a combination of…

» read the rest of this entry »What does it look like to aim for flow & sovereignty? There’s a kind of conversation that can surface all that’s present for people and allow a lot of sensemaking to occur. How do you get to such a conversation? There are various elements:

There’s also a matter of “what is the point of this conversation?” I think the best conversations have an orientation towards some fluid emergent combination of:

There might also be a specific topic, perhaps reflecting on an experience that everyone just went through together, or a question that one person has convened the conversation about.

I sometimes call these sorts of conversations a “co-what-now” process. “What now” is both about “what do we do now?” and also simply about making space to collectively hold the implications of whatever has just happened and what everyone’s sitting with. And when it’s working, there’s a lot of getting on the same page, that emerges clarity of the situation and of the next steps, and leaves people feeling satisfied and understood.

It seems to me like for some groups, eg ones oriented towards operating in a metarational way, it makes sense for them to aim towards having conversations like these on a consistent basis, not necessarily formally but in terms of the basic stance & attitude, and to incline towards whatever makes these conversations more satisfying.

And if one person is clear that the thing they need to do is some specific solo project, then perhaps they don’t participate in the co-what-now conversation at all (or beyond showing up to say “I’m gonna go do X”). There’s obviously a cost to having that person not present, but ideally there’s a collective sense of trusting that that person is taking that into account in their prioritizing. And if not, then that gets talked about. And maybe that person wants the large-group co-what-now conversations to happen at a different time of day or something. And maybe the conversations are recorded and the person listens to them later, or maybe someone else fills them in. Or maybe they just take some distance for a day or a week, and this is also workable.

And maybe one person isn’t actually internally clear about what they need to do, but they’re conflicted and tangled about something that feels really pressing and urgent but they don’t know how to solve it. In such a case, it’ll be hard for that person to settle into a collective train of thought & not-knowing because their situation will be dominating their experience. It may be possible for them to expand their awareness while holding onto that situation, so they can step into co-flow, although if they experience doing so and their situation often continues to remain unresolved at the end of the conversation, they will—accurately!—feel like the conversation is failing to address what’s most pressing to them, which will produce distrust and oscillation.

If they can’t expand their awareness enough to get into a kind of collective flow (which should be very rare by the time you get to a fully collaborative group but will be common with a partway there group) then there’s a sense in which what they need to do is whatever is going to solve their situation and liberate their attention so they can rest. That might not be a total solution, but something that makes the situation feel handled. And some or all of the other people might be able to support them in that with conversation or coaching or labor or whatever else, but also perhaps not. And the other people may or may not feel appetite towards supporting them in that. And the others may also want to still convene with each other, sensing into what-now in the context of the situation of one person being preoccupied by something else.

Note that one interesting phenomenon is that a conversation of 2 or more people yields a clear next step for one person, that makes obvious sense to do, but when they go to do it they find it’s not so obvious anymore. This can be for a few reasons:

This post is an excerpt from How we get there: a manual for bootstrapping meta-trust, my ebook on how to practice the art and science of group coherence in a way that’s exquisitely sensitive to top-down and bottom-up dynamics.