my close friend & colleague Michael Smith asked me

Question for you: In terms of Donald Hoffman’s interface interpretation thing, have you found a way to suss out how different someone else’s interface really is? Like, a way around the freshman philosophy problem of “Do you experience what I call ‘red’ as what I’d call ‘blue’, but you just call it ‘red’ too?” But deeper. Like, I wonder whether “thing” and “other” and “space” are coded radically differently between people. I’d expect that your perspective-taking practices might have hit on something there. So I’m curious.

The short answer is pretty well-articulated by @yashkaf here, but of course we can do a longer answer as well!

My overall sense is that first order human perception is in some important sense pretty similar, although of course blind people are in a very different world. This is what allows us to maintain the illusion that it’s NOT all an interface.

Yet simultaneously, our experiences of everything are radically, radically different to a degree that is hard to fathom. Hoffman completely dissolves “Do you experience what I call ‘red’ as what I’d call ‘blue’, but you just call it ‘red’ too?” There is never a “is your red my red?” in the abstract. That’s like asking “is this apple that apple?” like uhh no they are different apples.

And thus in some ways, my red actually has more in common with my own blue than it does with your red. Both of my colors are entirely composed of all of my own experiences.

However, of course, your and my “red” are more compatible than my “red” and “blue”, for many reasons that are obvious but I’ll say them anyway:

All of which would lead us to create compatible or commensurate interfaces with red, such that we don’t encounter many differences there when we go to talk about it. And the word “red” is an interface we share for referring to this pattern.

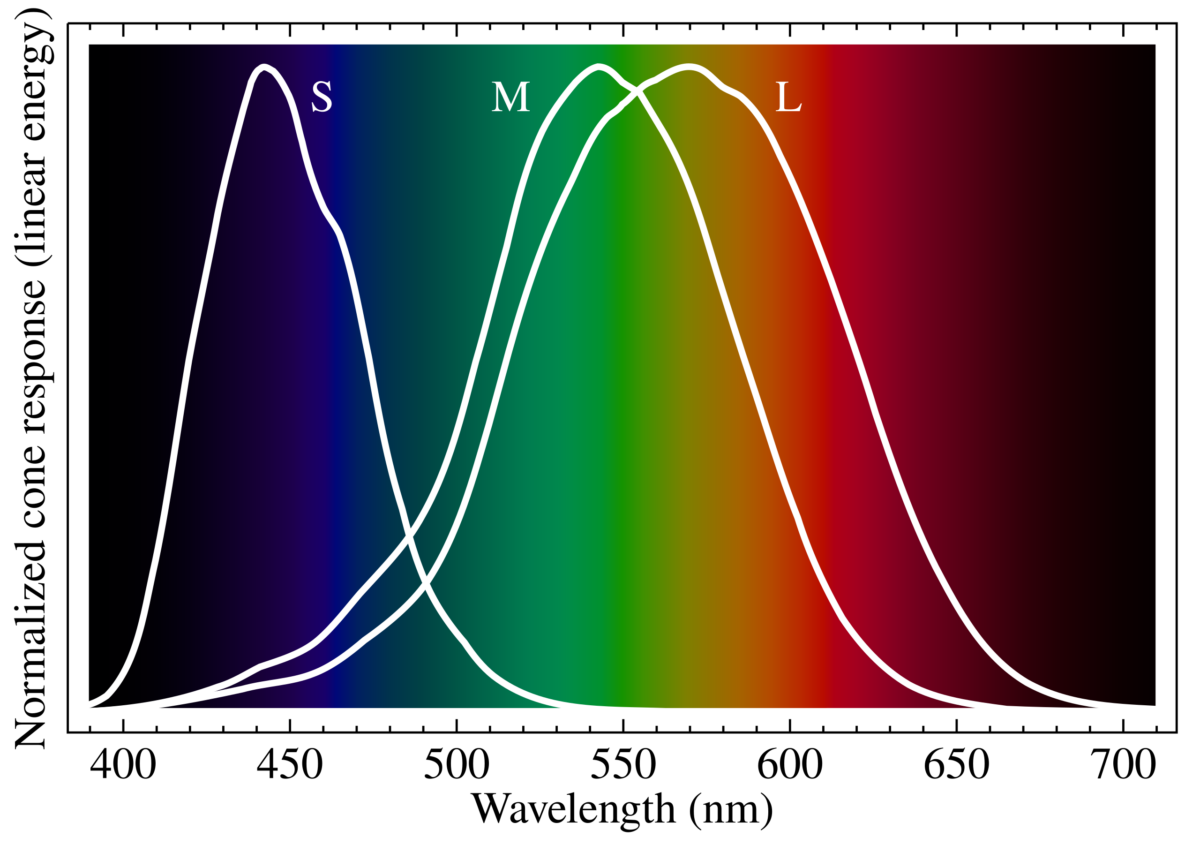

For what it’s worth I suspect actually that there are real subtle interfacial consequences to things like the fact that red is higher wavelength (lower energy) and for humans the fact that our red & green cone cells are much closer to each other than either is to blue (rods are between blue and green). I don’t know what the consequences are, but in an important sense it must matter. A tetrachromat (with a fourth kind of cell) would experience most colors quite differently. And of course colorblind people do.

However, the question of similarity or compatibility has an implicit context. You can do that with the apples too: are these two apples the same apple? Well in some sense of course they can be, if we know what we’re doing. They can be fungible or equivalent or undifferentiated, for some purpose.

And of course there are many ways in which our interfaces with the color red may be incompatible. When I try to point at these, they seem symbolic, somehow separate from the level of perception.

If you’re American and I’m Canadian (which I am) then you might be surprised to discover that for me, red is associated with the political “left wing” and blue with the political “right wing” (I’ll caveat that these concepts are themselves ever-shifting coalitions, not very natural categories). In fact, my way is more common in the rest of the world (and historical America); the phrase “red states and blue states” originated in 2000 with one particular TV announcer’s choice of colors (from the american flag). So is my red your blue? In this sense, yes!

And this is helpful to talk about color because it’s true for basically everything you could possibly want to talk about, and color perception is the MOST basic aspect of reality you can get, or close to it.

Which is maybe why the philosophers use it in this thought experiments!

Part of why Hoffman is so radical is that he highlights that it’s actually something-like-meaningless to say “my interface with Y and your interface with Y are more alike than those interfaces are with Carol’s”. They can’t be alike or unalike; they can’t be compared; they’re made out of different stuff! Mine are made out of my experiences and yours are made out of yours. That’s all in terms of the subjective interface, that is—you can obviously talk about our behaviors having something in common.

The actual question is ITSELF about interfaces again. Not “do you and I see this the same way?”—we don’t. Full stop. Next question.

And the next question is “do we want to describe how we see it, the same way?” on a propositional level.

Or “is my interface with Y able to interface with your interface with Y?” on more of a participatory level.

And it might be that we can effectively dance together, even though we have radically different descriptions of what dance is or what it means to us or how it works.

Having said that… there’s still clearly obviously a thing that we mean when we talk about difference, or perhaps distance. While writing this up, I intuitively used the metaphor of “how far apart people are” and this is actually a different metaphor than similarity, although we often use distance as a metaphor FOR similarity. And maybe we’ll also talk about what lies in that distance—is it a smooth pathway or a complex dance?

Ah yeah, it’s like, how complicated is the transformation we need to do to my interface in order to turn it into your interface? And in some super simple cases that transformation is basically a null operation except for the “entirely composed of your experience, rather than entirely composed of mine”, but they share the same structure and they sit in each of us in a similar way, so we round them to “same”.

In particular, mathematical objects can be extremely like this (though not as much as people might assume). Also if we have a shared experience of something happening to us both together, that can become a reference point (assuming we experienced it “much the same way”).

So let’s try that.

have you found a way to suss out how

differentfar away someone else’s interface really is?

There’s a kind of vast vector space here, and again it depends a bunch on context.

Like if there’s certain kinds of things at stake, and low trust, it can be very hard to get people to agree with boring statements that they would other times themselves utter as axiomatic premises (eg “we live in a society” or “humans are a kind of animal”) because they don’t want to allow the other person to set the frame and then force them using logic into accepting some conclusion they disagree with.

In general, one of the things I keep an eye out for is if there’s something where it’s easy for me to express it to Alice and hard for me to express to Bob. that’s a sign that me and Bob have a big weird gap/chasm/shear—in relation to that topic or knowing, not necessarily “in general”.

Interestingly I suspect it’s possible (tho not super common) that Bob could ALSO express relevant things to Alice that he can’t express to me.

This could be because Alice has a viewpoint that is a deep synthesis of mine and Bob’s. [depth perception metaphor]

More commonly, Alice has the ability to take either of our perspectives at a given time, but not both. So she can step into one frame or the other, and resonate with what we’re saying. and both of those are sort of workable ways of seeing things for her.

Whereas if I were to try to see things Bob’s way, or vice versa, it would produce some major discomfort for me because it would seem to violate something I know about the world.

It could be that Alice does not actually have that additional knowing, and that’s why she’s able to hear us, or it could be that she has that knowing and also has some additional knowing that makes it not-an-issue.

Important to track here is a principle I have which is something like “everybody contains explanations of literally everything they have ever experienced. Necessarily this involves making a bunch of absurd generalizations”.

But people can have very compartmentalized explanations, where they can’t actually simultaneously explain X and Y, and if you get them to try they get distracted or flustered or angry.

This is kind of developmental stuff I guess also, except it doesn’t necessarily map onto any common ladder like Kegan stages.

As for…

Like, I wonder whether “thing” and “other” and “space” are coded radically differently between people.

This seems very very true to me, not just of the words but of what we would consider the referent.

[this post is half-baked and I didn’t finish this part and as of the moment I’m publishing it I’m not even sure what exactly I was gonna get at here]

It occurs to me, in the shower, that a lot of my life is preoccupied by this question. It’s a good theme, for Malcolm Ocean. Whose job is this?

My “what if it were good tho?” YouTube series and website is about the role of design: how each day, people are pulling their hair trying to workably interface with systems, wasting hours of their life, and feeling stupid or ashamed because they can’t figure it out, when in many of these cases an extra couple of minutes’ thought on the part of the person who designed it or made it would have made the whole experience so smooth it would have gone as unnoticed as the operation of the differential gearing in your car that makes turns not result in wheels skipping on the ground as the outer one needs to travel further than the inner one. That guy just works! That problem is so solved most people never even realize it was ever a problem.

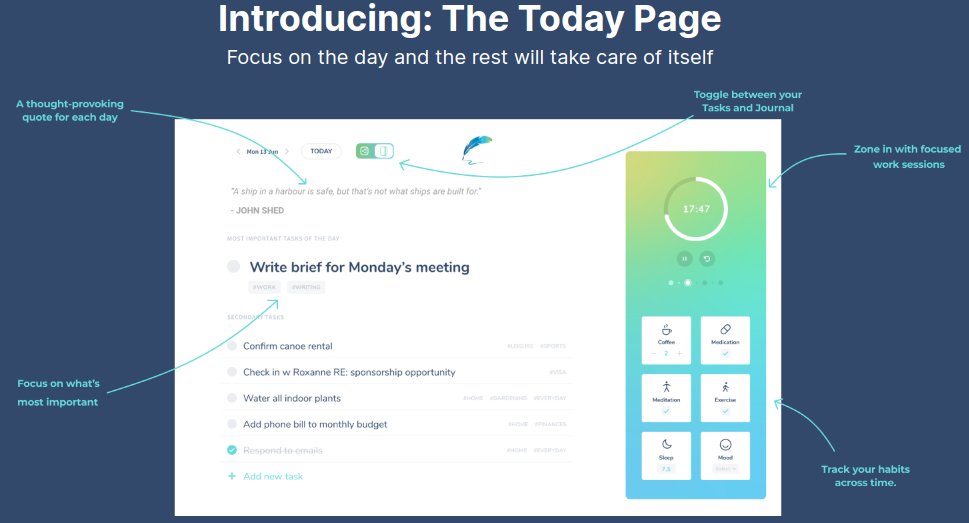

My app, Intend, is about the question of what you want to do with your life: about consciously choosing what your job is. It’s also about figuring out what to do right now, in light of the larger things you want to do, and differentiating something someone else wants you to do from something you want to do, so you don’t accidentally live somebody else’s vision for your life instead of yours. Moreover, it helps keep you from being saddled with dozens or hundreds of stale tasks merely because past-you vaguely thought they were a good idea or at least worth putting on a list.

My work in communication, trust, and the human meta-protocol, is about teasing apart the nuances of exactly who is responsible for what. Some of that has been focused around creating post-blame cultures, and I’ve recently come to a new impression that what blame is (aside from “the thing that comes before punishment”) that I could summarize as “a type of explanation for why something went wrong that assigns responsibility crudely rather than precisely and accurately-by-all-parties’-accounts”. In other words, it gets the “whose job is this?” question wrong, and people can tell.

My mum told me that as a kid I had a very keen sense for justice and injustice, and this feels related to how I think about the design stuff as well as other questions. My ethical journey over the last years has involved a lot of investigation of questions around what things are my job, and what things are not my job, and how to tell the difference. And how to catch my breath, and how to reconcile the fears I’ve had of not trying hard enough. And how to tell when the messages about how to be a good person are crazy.

As I said, my longstanding beef with bad design can be seen as frustration at designers and builders not doing their job. I say “builders” because some of them don’t even realize that part of their job includes design. My partner, Jess, just shared with me a perfect case study of this. She’d been having trouble getting her psych crisis non-profit registered for some California government thing, because the form needed her number from some other registration, but when she put in the number the form said it was invalid (with no further clues). She tried a different browser, tried a bunch of other numbers from the document that had the supposed number, called the people who had given her the number to make sure it was the right one given that it wasn’t super well-labeled, and I even tried poking at the javascript on the page to turn off the validation altogether, but nothing worked.

A couple weeks later she texted me:

» read the rest of this entry »As someone currently experiencing substantial amounts of collective intelligence on Twitter, here’s some of what I’m seeing as the emerging edge of new behaviors and culture, and one bottleneck on our capacity to think together and make sense of the world.

Some of us are pioneering a new experience of Twitter that’s amazing, and that wouldn’t be possible on any other platform that exists today.

Conversation is thinking together.

Collective intelligence is, at its core, good conversation.

Many people, on and off Twitter, think of it as a shouting fest, and parts of it are. And… at the same time, on the same app, with the same features but some different cultural assumptions, there are pockets where people are meeting the others, making scientific progress, falling in love, healing their trauma, starting businesses together, and sharing their learning processes with each other.

Those sorts of metrics—as hard to measure as they are—form a kind of north star for Twitter. This creature has the potential to be the best dating app (for some people) and a way better place for finding your dream job than LinkedIn (for many people). And so on.

Cities have increased creativity & innovation per capita per capita, ie when you add more people each person becomes more, because more people & ideas can bump into each other. The internet is a giant city, and this is far more true on Twitter than any other platform, particularly because of how tightly it allows the interlinking of ideas with Quote Tweets.

Twitter is very much about “what’s happening [now]” but, as the world has been collectively realizing over the past decade, simply knowing “what’s happening” in some isolated way is meaningless and disorienting. Meaning comes from filtering & distilling & contextualizing what’s happening, and this is part of what Twitter is already so brilliant for, because everyone can talk to everyone and the ultra-short-form non-editable medium encourages you to tweet today’s thoughts today rather than drafting them today, editing them tomorrow, then scheduling them for next week’s newsletter.

When someone makes a quote-tweet, they’re essentially saying “I have some thoughts I’d like to share, that relate to the tweet here”. This might be a critique of the quoted tweet/thread, or it might be using the quoted material as a sort of footnote of supportive evidence or further reading or ironic contrast. This meta-commentary is very powerful, whether it’s used by someone reflected “I think what I really meant to say here was” or someone framing a thread they just read as an answer to a particular question they and their followers might care about.

Currently, however, it’s impossible to QT two or more tweets at once. This means that in the natural ontology of Twitter, there is no way to properly compare or contrast or relate different thoughts.

This contributes, I think, to the fragmented & divergent quality of thinking on Twitter: the structure of the app makes it hard to express convergent thoughts. You can use screenshots… but then all context & interlinking & copy-pastability is destroyed. You can have a meta-thread that pulls a bunch of things together… but each tweet in that thread is still only referencing one other tweet, so there’s no single utterance that performs the act of relating other utterances.

The amount of utterances that need to connect two other pre-existing utterances is huge. Thoughts shaped like:

Similarly to how the #hashtag & @-mentions evolved from user behavior, and the Retweet functionality evolved out of people copying others tweets and tweeting them out with “RT @username: ” at the start, and Quote Tweeting evolved out of people pasting a link to another tweet within their tweet… MultiQT is a natural evolution of the “screenshot of multiple tweets” and “linking tweets together as a train of thought using multiple QTs in a thread” behaviors.

I didn’t even realize quite how much I’d want this until I started mocking up the screenshots below by messing with the html in the tweet composer and being so sad I couldn’t just hit “Send Tweet”. I can already tell that like @-mentions and RTs, once we’re used to this it’ll feel absurd to think we ever lived without it.

» read the rest of this entry »I’ve recently added a new page to my website called Work With Me. The page will evolve over time but I’m going to write a short blog post about the concept and share the initial snapshot of how it looks, for archival purposes.

There’s a lot of stories I could tell here. I’ll tell a few slightly fictional versions before getting to the actual series of events that occurred.

One fictional version is that I was inspired by Derek Sivers’ /now page movement but I wanted something that created more affordances for people to connect with me, including regarding opportunities that I’m not actively pursuing now on my own. This is true in the sense that I was thinking about /now by the time I published the page, and in the sense that I would love to see Work With Me pages show up on others’ sites. You could be the first follower, who starts a movement!

Another fictional version is that I was thinking about my Collaborative Self-Energizing Meta-Team Vision and wondering how to make more surface area for people to get involved. I’m someone who thinks a lot about interfaces, not just between humans and products but also between humans and other humans, and it occurred to me that there wasn’t a good interface for people to find out how to plug in with me to work on self-energizing projects together. So I made this page! This was also on my mind, but it’s still not quite how it happened.

» read the rest of this entry »Some years ago, I invented a new system for doing stuff, called Complice. I used to call it a “productivity app” before I realized that Complice is coming from a new paradigm that goes beyond “productivity”. Complice is about intentionality.

Complice is a new approach to goal achievement, in the form of both a philosophy and a software system. Its aim is to create consistent, coherent, processes, for people to realize their goals, in two senses:

Virtually all to-do list software on the internet, whether it knows it or not, is based on the workflow and philosophy called GTD (David Allen’s “Getting Things Done”). Complice is different. It wasn’t created as a critique of GTD, but it’s easiest to describe it by contrasting it with this implicit default so many people are used to.

First, a one-sentence primer on the basic workflow in Complice:

There’s a lot more to it, but this is the basic structure. Perhaps less obvious is what’s not part of the workflow. We’ll talk about some of that below, but that’s still all on the level of behavior though—the focus of this post is the paradigmatic differences of Complice, compared to GTD-based systems. These are:

Keep reading and we’ll explore each of them…

» read the rest of this entry »Originally written October 19th, 2020 as a few tweetstorms—slight edits here. My vision has evolved since then, but this remains a beautiful piece of it and I’ve been linking lots of people to it in google doc form so I figured I might as well post it to my blog.

Wanting to write about the larger meta-vision I have that inspired me to make this move (to Sam—first green section below). Initially wrote this in response to Andy Matuschak’s response “Y’all, this attitude is rad”, but wanted it to be a top-level thread because it’s important and stands on its own.

Hey @SamHBarton, I’m checking out lifewrite.today and it’s reminding me of my app complice.co (eg “Today Page”) and I had a brief moment of “oh no” before “wait, there’s so much space for other explorations!” and anyway what I want to say is:

How can I help?

Because I realized that the default scenario with something like this is that it doesn’t even really get off the ground, and that would be sad 😕

So like I’ve done with various other entrepreneurs (including Conor White-Sullivan!) would love to explore & help you realize your vision here 🚀

Also shoutout to Beeminder / Daniel Reeves for helping encourage this cooperative philosophy with eg the post Startups Not Eating Each Other Like Cannibalistic Dogs. They helped mentor me+Complice from the very outset, which evolved into mutual advising & mutually profitable app integrations.

Making this move, of saying “how can I help?” to a would-be competitor, is inspired for me in part by tapping into what for me is the answer to “what can I do that releases energy rather than requiring energy?” and finding the answer being something on the design/vision/strategy level that every company needs.

» read the rest of this entry »Another personal learning update, this time flavored around Complice and collaboration. I wasn’t expecting this when I set out to write the post, but what’s below ended up being very much a thematic continuation on the previous learning update post (which got a lot of positive response) so if you’re digging this post you may want to jump over to that one. It’s not a prerequisite though, so you’re also free to just keep reading.

I started out working on Complice nearly four years ago, in part because I didn’t want to have to get a job and work for someone else when I graduated from university. But I’ve since learned that there’s an extent to which it wasn’t just working for people but merely working with people long-term that I found aversive. One of my growth areas over the course of the past year or so has been developing a way-of-being in working relationships that is enjoyable and effective.

I wrote last week about changing my relationship to internal conflict, which involved defusing some propensity for being self-critical. Structurally connected with that is getting better at not experiencing or expressing blame towards others either. In last week’s post I talked about how I knew I was yelling at myself but had somehow totally dissociated from the fact that that meant that I was being yelled at.

“It was a pity thoughts always ran the easiest way, like water in old ditches.” ― Walter de la Mare, The Return

You’re probably more predictable than you think. This can be scary to realize, since the perspective of not having as much control as you might feel like you do, but it can also be a relief: feeling like you have control over something you don’t have control over can lead to self-blame, frustration and confusion.

One way to play with this idea is to assume that future-you’s behaviour is entirely predictable, in much the same way that if you have a tilted surface, you can predict with a high degree of accuracy which way water will flow across it: downhill. Dig a trench, and the water will stay in it. Put up a wall, and the water will be stopped by it. Steepen the hill, and the water will flow faster.

So what’s downhill for you? What sorts of predictable future motions will you make?

There are a lot of interfaces that irk me, not because they’re poorly designed in general, but because they don’t interface well with my brain. In particular, they don’t interface well with the speed of brains. The best interfaces become extensions of your body. You gain the same direct control over them that you have over your fingertips, your eyes, your tongue in forming words.

This essay comes in two parts: (1) why this is an issue and (2) advice on how to make the best of what we’ve got.

One thing that characterizes your control over your body is that it (usually) has very, very good feedback. Probably a bunch of kinds you don’t even realize exists. Consider that your muscles don’t actually know anything about location, but simply exerting a pulling force. If all of the information you had were your senses of sight and touch-against-skin, and the ability to control those pulling forces, it would be really hard to control your body. But fortunately, you also have proprioception, the sense that lets you know where your body is, even if your eyes are shut and nothing is touching. For example, close your eyes and try to bring your finger to about 2cm (an inch) from your nose. It’s trivially easy.

One more example that I love and then I’ll move on. Compensatory eye movements. Focus your gaze at something at least two feet away, then bobble your head around. Tried it? Your brain has sophisticated systems (approximating calculus that most engineering students would struggle with) that move your eyes exactly opposite to your head, so that whatever you’re looking at remains in the center of your gaze and really quite incredibly stable even while you flail your head. This blew my mind when I first realized it.

The result of all of these control systems is that our bodies kind of just do what we tell them to. As I type this, I don’t have to be constantly monitoring whether my arms are exerting enough force to stay levitated above my keyboard. I just will them to be there. It’s beyond easy―it’s effortless.

Now, try willing your phone to call your friend. You’re allowed to communicate your will using your voice, your hands, whatever. Why does it take so many steps, or so much waiting?

Growing up, you make decisions, but it’s kind of like a Choose Your Own Adventure Book.

Finally, you reach grade 12. It’s time to choose which university to attend after high school!

- To check out the prestigious university where your dad went, turn to page 15.

- To visit the small campus nearby that would be close enough to live at home, turn to page 82

- To take a road trip with friends to the party college they want to go to, turn to page 40.

That’s a decent set of choices. And you know, there exist hypothetical future lives of yours that are really awesome, along all pathways. But there are so many more possibilities!

Both personal experience and principles like Analysis Paralysis agree that when you have tons of choices, it becomes harder to choose. Sure. But, to the extent that life is like the hypothetical Choose Your Own Adventure Book (hereafter CYOAB) above, I don’t think the issue is that there aren’t enough options. The issue lies in the second sentence, which contains a huge assumption: that in grade 12, it’s time to choose a university to attend. Sure, maybe later in the book is a page that says something about “deferring your offer” to take a “gap year”, but even that is presented as just an option among several others. And so it goes, beyond high school and post-secondary education and into adulthood.

What you don’t get to do, in a CYOAB, is strategize about what you want and how to get it. » read the rest of this entry »