In my 2019 yearly review: Divided Brain Reconciled by Meaningful Sobbing, I experimented for the first time in a while with setting a theme for the upcoming year: Free to Dance. And lo, while I didn’t think about it that often, it’s proved remarkably relevant, in ways I couldn’t have anticipated.

The original concept of the phrase came in part from having just picked up Bruce Tift’s book Already Free: Buddhism Meets Psychotherapy on the Path of Liberation, which by early January I could tell would be a major book of my year. Another related dimension of it was something I realized in doing some of the emotional processing work last year, which was that parts of me sometimes still kind of think I’m trapped at school where I’m supposed to sit still at my desk, among other indignities.

The other main piece was observing at a couple of points that I sometimes seem to move through the world as if I’m dancing, and other times much more heavily. During an exercise at the Bio-Emotive retreat midsummer, we were asked to reflect on a question something like “how would I be if I were showing up most brilliantly/beautifully?” And what arose for me is something like “I think I’d always be dancing.”

So all of these layers mean that the social isolation of the pandemic didn’t put much of a specific damper on this life theme, even though I was hardly free to go to dance events (except some lovely outdoor bring-your-own-partner contact improv events that a friend hosted). I had been intending to travel the world a bit, to San Francisco, perhaps Austin, perhaps the UK, and none of those visits happened.

What did happen?

» read the rest of this entry »Originally written October 19th, 2020 as a few tweetstorms—slight edits here. My vision has evolved since then, but this remains a beautiful piece of it and I’ve been linking lots of people to it in google doc form so I figured I might as well post it to my blog.

Wanting to write about the larger meta-vision I have that inspired me to make this move (to Sam—first green section below). Initially wrote this in response to Andy Matuschak’s response “Y’all, this attitude is rad”, but wanted it to be a top-level thread because it’s important and stands on its own.

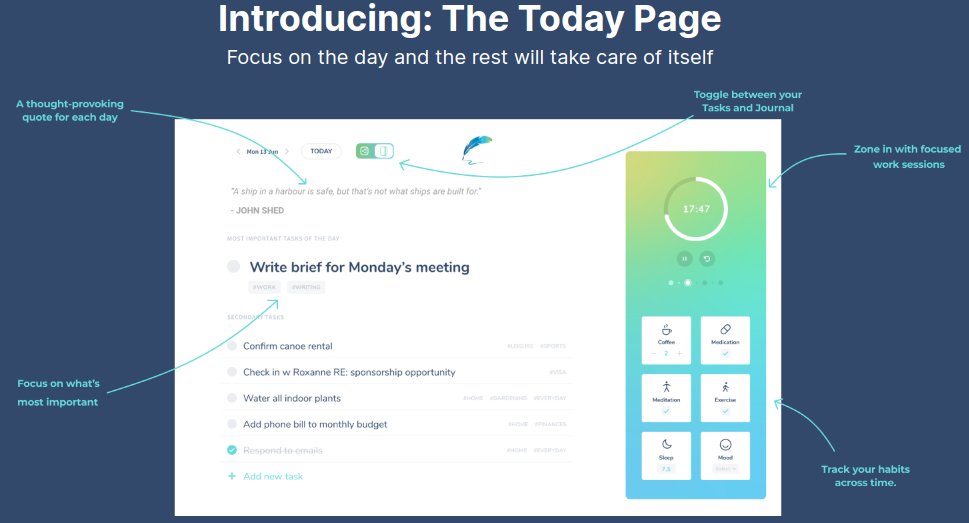

Hey @SamHBarton, I’m checking out lifewrite.today and it’s reminding me of my app complice.co (eg “Today Page”) and I had a brief moment of “oh no” before “wait, there’s so much space for other explorations!” and anyway what I want to say is:

How can I help?

Because I realized that the default scenario with something like this is that it doesn’t even really get off the ground, and that would be sad 😕

So like I’ve done with various other entrepreneurs (including Conor White-Sullivan!) would love to explore & help you realize your vision here 🚀

Also shoutout to Beeminder / Daniel Reeves for helping encourage this cooperative philosophy with eg the post Startups Not Eating Each Other Like Cannibalistic Dogs. They helped mentor me+Complice from the very outset, which evolved into mutual advising & mutually profitable app integrations.

Making this move, of saying “how can I help?” to a would-be competitor, is inspired for me in part by tapping into what for me is the answer to “what can I do that releases energy rather than requiring energy?” and finding the answer being something on the design/vision/strategy level that every company needs.

» read the rest of this entry »This post was adapted from a comment I made responding to a facebook group post. This is what they said:

Trusting isn’t virtuous. Trusting should not be the default. Care to double crux me?

(I believe that this was itself implicitly responding to yet others claiming the opposite of it: that trust is virtuous and should be a default/norm.)

My perspective is that it’s not about virtue at all. It’s just about to what extent you can rely on a particular system (a single human, a group of humans, an animal, an ecosystem, a mechanical or software system, or whatever) to behave in a particular way. Some of these ways will make you inclined to interact with that system more; others less.

We are, of course, imperfect at making such discernments, but we can get better. However, people who are claiming it’s virtuous to trust are probably undermining the skill-building by undermining peoples’ trust in whatever level of discernment they do have: is it wrong if I don’t trust someone who is supposedly trustworthy? The Guru Papers illustrates how this happens in great detail. I would strongly recommend that book to anyone wanting to understand trust.

If I were to gesture at a default stance it would be neither “trust” nor “distrust” nor some compromise in between. It would be a stance of trust-building. » read the rest of this entry »

One of the biggest things I’ve learned over the past year is how to truly let go of regret.

(Psst: if you’ve got Spotify, hit play on this track before you keep reading. Or here’s a YouTube link. I’ll explain later.)

A few months ago, in September, I went to a tantra yoga workshop called the Fire & Nectar retreat. The event involved a fair bit of yoga and meditation, but what was most powerful for me were the teachings on non-dualism. A lot of it made deep, immediate sense to me, and there were also pieces that were met with a lot of resistance.

One of the most challenging things that our teacher Hareesh said was this:

If you had a chance for a do-over, would you choose for everything to go exactly the same?

If not, you have not yet surrendered.

He clarified that this wasn’t talking about a dualistic sort of surrender, more like surrendering to reality. I seem to recall he was quoting someone, but I can’t find a source in my notes or on the internet. At any rate, this was a thing that he said, and I immediately recognized it as containing a perspective that I didn’t understand. A perspective that I feared.

I recognized it as a perspective that I’d been in a battle with for several years.

Another personal learning update, this time flavored around Complice and collaboration. I wasn’t expecting this when I set out to write the post, but what’s below ended up being very much a thematic continuation on the previous learning update post (which got a lot of positive response) so if you’re digging this post you may want to jump over to that one. It’s not a prerequisite though, so you’re also free to just keep reading.

I started out working on Complice nearly four years ago, in part because I didn’t want to have to get a job and work for someone else when I graduated from university. But I’ve since learned that there’s an extent to which it wasn’t just working for people but merely working with people long-term that I found aversive. One of my growth areas over the course of the past year or so has been developing a way-of-being in working relationships that is enjoyable and effective.

I wrote last week about changing my relationship to internal conflict, which involved defusing some propensity for being self-critical. Structurally connected with that is getting better at not experiencing or expressing blame towards others either. In last week’s post I talked about how I knew I was yelling at myself but had somehow totally dissociated from the fact that that meant that I was being yelled at.

The process “giving feedback” is outdated. Or limited, at least.

Let’s do a post-mortem on a post-mortem, to find out why…

My friend Benjamin (who works with me on both Complice and the Upstart Collaboratory culture project) and I had an experience where we were making some nachos together, and… long story short: most of them burnt. We then spent a bit of time debriefing what had happened. What was the chain of events that led to the nachos burning? What had we each experienced? What did we notice?

This yielded a bunch of interesting and valuable observations. One thing that it did not yield was any plans or commitments for how we would do it differently in the future. Anything like “So when [this] happens next time, I’ll do [that], and that will act as a kind of preventative measure.”

Given that lack of future plans or commitments, one might ask: was it a waste of time? Did we not really learn anything? Will things just happen the same way again? » read the rest of this entry »

Much of this post was originally drafted a couple years ago, so the personal stories described in here took place then. I’m publishing it now in part because the novella that inspired it—Ted Chiang’s Story of your Life—has recently been made into a feature-length movie (Arrival). In some contexts, it might make sense to say that this post may contain spoilers for SOYL; in this particular one, that would be hilariously ironic. Even after reading this post, the story will be worth reading.

This post begins, like so many of mine, with a conversation with Jean, the founder of the Upstart Collaboratory, where she and I and others are practicing the extreme sport of human relating. Jean remarked that a conversation she’d had earlier that day had been really good, then noted that she’d already told me that.

I replied, “Well, yes, and it was meaningful to me that you said it again. On the most basic level, it implies that on some level you felt you hadn’t yet conveyed just how good the conversation had been.” Then I shared with her something I’d heard from Andrew Critch, at a CFAR workshop. (Quote is from memory)

If someone says “something” to you, then that doesn’t mean that “something” is true. It also doesn’t necessarily mean that that person believes that “something” is true. Incidentally, it also doesn’t necessarily mean that they think that you don’t already agree with them that “something”. It really just means that, at the moment they said it, it made sense to them to say “something”. To you.

I was having a lot of challenge figuring out where to start this one. For some reason, the Object/Process/Meta structure I used the past three years doesn’t feel like it makes sense this year. Maybe because this year a lot of the object-level “stuff I did” was itself process- or meta-level.

The first thing I need to get out of the way is that as of last week, I’m using the Holocene calendar, which means that instead of writing my 2016 CE review, I’m writing my 12016 HE review. It’s the same year, but I’m experimenting with living in the thirteenth millennium because (4-6 years after) the birth of Christ is a weird start time for a bunch of reasons. Better is about 12,000 years ago, around the start of human civilization. There might be a slightly more accurate year, but the nice thing about just adding 10,000 years is that it means you don’t have to do any math to convert between CE and HE: just stick a 1 on the front or take it off. This in turn means I can use it in public-facing works and while it might be a little confusing, it’s still easily-understood. Here’s a great YouTube video on the subject. I’ll tell you if/how this affects my thinking during next year’s yearly review, after I’ve been using it for awhile.

Okay, 12016. » read the rest of this entry »

So we’re trying to upgrade our mindsets.

Here’s my formulation of what we’ve been doing at my learning community, which has been working well and shows a lot of potential to be even more powerful:

With deep knowledge of why you want to change, make a clear commitment, to yourself. Then, share that commitment with people who support you, and make it common knowledge.

(Update post-2020: the “working well” was illusory. It was very effective at causing temporary wins, followed by relapses. I talk about those dynamics here, and more generally about how “Mindset choice” is a confusion.)

I’ve written before about a hard vs soft distinction: with hard accountability, there is a direct, specific negative outcome as a result of failing to meet your commitment. This is the domain of commitment contracts (“if I don’t write this paper by tuesday 8pm, I’ll pay you $50”) and systems like Beeminder. With soft accountability, you’re making a commitment to paying attention to your behaviour in the relevant area and shaping it to be more in line with your long-term vision.

Read that post to find out more about the distinction. Here I just want to note that hard accountability has some disadvantages in fuzzy domains, for instance in changing habits of thought. One is that if there’s a grey area, it’s then very unclear if you’ve succeeded or failed at the committed behaviour, and you need to know. Furthermore, it’s likely to be the case that the behaviour change you want to make isn’t exactly the same as the one you can measure, which means that your commitment is now somewhat at odds with your goal, in that you’re optimizing for the wrong thing.

This post was co-written with my friend Duncan Sabien, a very prolific doer of things. He had the idea of writing the article in a sort of panel-style, so we could each share our personal experiences on the subject.

Malcolm: At the CFAR alumni reunion this August, my friend Alton remarked: “You’re really self-directed and goal-oriented. How do we make more people like you?”

It didn’t take me long to come up with an answer:

“I think we need to get people to go and do things that nobody’s expecting them to do.”

Duncan: When I was maybe nine years old, I had a pretty respectable LEGO collection dropped into my lap all at once. I remember that there was one small spaceship (about 75 or 80 pieces) that I brought along to summer camp, with predictable results.

I found myself trying to piece the thing back together again, and succeeded after a long and frustrating hour. Then, to be absolutely sure, I took it completely apart and reassembled it from scratch. I did this maybe forty or fifty times over the next few weeks, for reasons which I can’t quite put my finger on, and got to where I could practically put the thing together in the dark.

These days, I have an enormous LEGO collection, made up entirely of my own designs. My advice to pretty much everyone: